Who should own personal data? Is it the users? Is it the company harvesting it? While we wrestle with our answers to this, data collected by companies is being sold to third parties. It is available to anyone willing to pay. Should companies be allowed to sell users’ personal data?

The meteoric rise in the use of social media has diminished the expectation of privacy online. The world is slowly coming to terms with it after major scandals such as the 2016 US election and Brexit. The rapid growth of artificial intelligence in recent years and its effects on society have become critical issues for how the world will be shaped in the future.

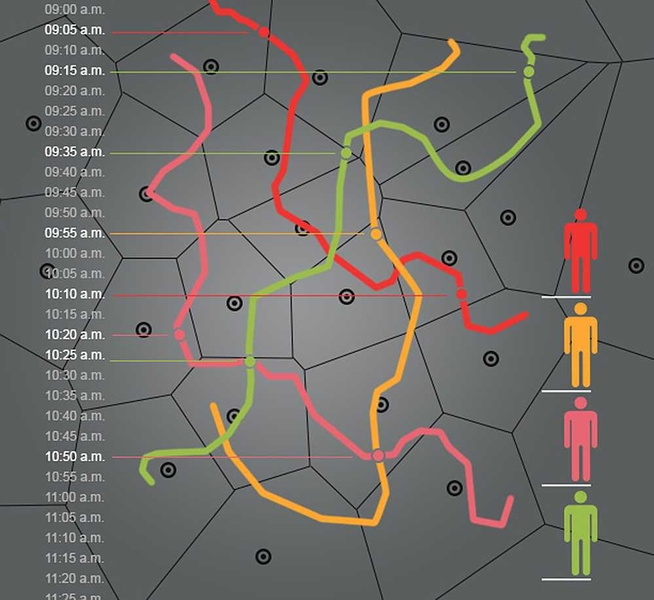

Events like these have sparked a public conversation about data ownership. Should companies that collect user data be allowed to sell it? How is data sold though? Apart from the basic way of buying and selling, there’s another way called real-time bidding. Developers and publishers often auction spaces on their apps to show advertisements. These ads are often unique to individual users and are bid upon by advertisers. To show personalised ads to relevant users, technology companies curate and put user profiles up for bidding. Visiting an online page kicks off a bidding process where advertisers are sent data like the visitor’s interest, IP address, demographics, and location. The advertisers choose how much they would like to bid to show an advertisement to this visitor. Even though there is just one winning bid, all the advertisers get to see the user data.

We think that (re)selling user data has more harm than benefit and should not be allowed. Nowadays, data is being collected at an unprecedented scale. The consequences of this data falling into wrong hands are egregious — worse if it is available for sale. There’s no risk control on who can buy this data. For instance, a 20-year-old woman was murdered by her classmate who paid an online data broker $45 to obtain her personal details. Similarly, it costs approximately $160 to identify people visiting abortion clinics via geolocation data. This is then used to show targeted ads, in real-time, to women inside these clinics to change their minds. It can also be bought by someone with motivations to harass and intimidate women considering abortion.

Another issue is the weakening of democratic institutions. For instance, freedom to assemble and protest is guaranteed in most countries. The police have, however, begun using AI to identify political protesters in crowds. Similarly, even though in Carpenter v. United States, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the government needs a warrant to compel companies to produce sensitive data such as the user’s location, the government is taking advantage of some workarounds. Namely, they are paying data brokers to obtain this kind of information. This phenomenon presents civil rights issues in addition to privacy considerations. This is dangerous for democracy. It allows those in power to bring down movements through intimidation and control.

In the wrong hands, personal information may be the subject of conscious or unconscious biases that target people of colour and other marginalised communities. Online bad actors may utilise a person’s race, colour, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, or gender identity to determine that person’s eligibility for essential services like insurance or health care. Based on the demographic information, different prices are offered for the same service.

Proponents of the data broking industry also state that because data is collected in an anonymized manner, it does not harm individuals. But it is known that anonymised data can be re-identified when combined with auxiliary data. For example, Lantana Sweeney was able to identify 87% of the US population using only the zip code, date of birth, and gender by analysing the census records. Similarly, in another study, researchers found that it is possible to identify 95% of the 1.5 million cellphone users by approximately 4 cell tower pings in a year. This becomes scarier as hospitals and pharmacies sell anonymised patient data.

Another argument in favour of selling personal data is that companies can understand the consumer’s pain points and come in their support, by meeting their needs. These insights help develop new services, like a personalised advertisement which means that the users will receive only relevant offers and content. A recent United States’ Federal Trade Commission report stated, “Data broker products help to prevent fraud, improve product offerings, and deliver tailored advertisements to consumers.”. We oppose this argument because these companies tailor the way the world is presented to specific users – which can be harmful and create an illusion of the real world – only based on their online preferences which don’t provide the complete picture of someone. It could also do more harm by advertising products that will sell more to a vulnerable demographic. For example, advertising predatory loan services to people living in poverty or on the verge of bankruptcy. The report notes that a fraud prevention process based on collected personal data also poses a risk to consumers. It says, “…if a consumer is denied the ability to conclude a transaction based on an error in a risk mitigation product, the consumer can be harmed without knowing why.”

The risks far outweigh the benefits provided by selling personal data in both number and severity. No risk control on who can buy data poses a threat to individuals such as abortion-seeking women and survivors of domestic abuse. It threatens democracy because it allows the government to buy data that would normally require a court warrant. It also allows political parties and external entities to spread misinformation and create unrest in a country. Finally, it affects people in minority demographics through doxing or unfair service offerings.

Privacy laws do not keep pace with the Internet’s evolution, leaving a large percentage of the population vulnerable. The personal information they may share to conduct regular, daily activities online can be used against them. Our point of view is that to eliminate this discrimination, the protection of personal data while people browse the internet is critical. Companies should not be allowed to engage in data practices that are harmful or abusive to consumers.