By Elmamoune Bouchareb and Maria Ismini Katsouli

Western colonial domination over the Global South occurred between

the 15th and 20th centuries, during which European countries exerted

power and dominance over regions in Africa, Asia and the Americas. European colonial powers accumulated vast amounts of resources and wealth through the extractive appropriation of colonized lands. Extracting natural resources from other lands into capital is a colonial framework which still persists through neo-colonialism. After historical colonialism, many former colonies achieved economic decolonization and freedom, yet political decolonization has not consistently followed. Countries like France continue to exert significant influence over the politics, language and state affairs of their former colonies. Today, data colonialism might be paving the way for a new capitalism variant. The ongoing colonial wealth transfer and oppression effects appear in the economic, cultural, and political exclusion of African people from AI technology development. In pursuit of profit, companies often prioritize efficiency and scalability over fairness and accountability, sidelining the ethical considerations necessary for equitable technology deployment.

We argue that AI is a colonial tool whose development is rooted in deeply historical and economic contexts. Furthermore, it is inherently biased and underlined by capitalist frameworks that have also pre-empted colonial inquisitions. However, it has potential to change in the long term with the application of de-colonial theories.

Why is AI a colonial tool?

Big Tech Companies, Data Colonialism, and Power

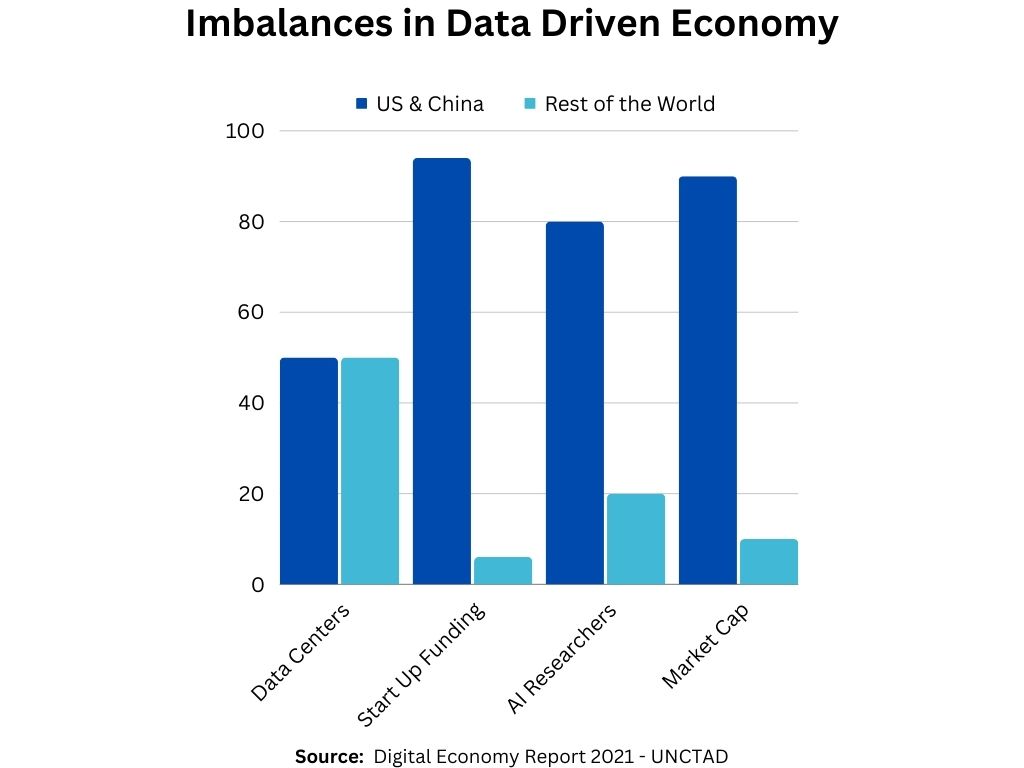

Currently AI is dominated by big tech companies in the United States and China. These global superpowers account for half of the world’s hyper-scale data centers, 94 percent of start up funding and most of AI research according to UNCTAD statistics.

Big tech firms have capitalized on their data and technical infrastructures monopolies to extract, appropriate, and control the majority of the Global South’s data. Platforms like Facebook, Google, and TikTok transform user interactions into sellable data for advertisers, government, or law enforcement, exploiting underdeveloped local AI governance laws. While these companies arguably contribute to local economies, a report indicates they’ve avoided paying $2.8 billion in taxes, money that could fund essential public services. Moreover, AI jobs in the Global South often involve exploitative conditions, including underpayment and the psychological distressful labor. Big tech companies like OpenAI and Facebook are among those who are disregarding AI ethics for cheap and exploitable labor in the Global South. Ultimately, data colonialism is forging a new form of capitalism, one where the colonial transfer of wealth manifests itself by the marginalization of African people in the development of AI technologies.

Considering that the US and China own the majority of AI data infrastructure, doesn’t that necessarily imply that AI isn’t inherently a tool brought up by the colonial control of the West over the Global South?

China is currently a global superpower with neocolonial interests in Africa where they have been able to compete with prior colonial countries by achieving soft power through loans, investments, political influence and migration. China’s public infrastructure has has reached a saturation point which can be detrimental to it’s growth rate expectations. As a result China has looked to sell it’s infrastructure building capabilities to African countries in exchange for contracts that grant ownership to ports and resources in the African continent. While China’s AI infrastructure is not as observable as the Western infrastructure due the barriers of entry to the Chinese internet. We are now seeing the emergence of global Chinese platforms that aim to compete with social media and e-commerce giants such as TikTok and Temu. These platforms ultimately are the Chinese response to the Western competition and are also being used to farm data and ultimately reach the same monopolistic dominance over that sector. While Chinese neocolonial practices in Africa are gaining the approval of the popular sentiment of African people, they ultimately have the same goal in mind as Western colonial practices: gain power and extract the resources necessary to generate more capital.

AI is inherently biased

Considering that the vast majority of AI research, data and development is monopolized by two countries, AI is vulnerable to reflecting biases ingrained in the environments from which is is developed. AI is mainly being developed by a group of educated Western and Chinese engineers that reflect the values and outlooks of their societies. The Global South has to rely on the AI infrastructure of these superpowers which is developed without the consideration of their social, economic, intellectual, and political contexts. Today, the majority of literature regarding AI ethics is biased toward Euro-American values and perspectives. AI Governance frameworks are mostly concerned with developing universal technology policies to govern AI, failing to address the local contexts and concerns of the Global South. AI regulatory frameworks and policies in the Global South have not been developed adequately which could further problems of injustice and inequality in the continent. AI research tends to lack consideration for the African context as it relates to needs of local communities. Furthermore, there is a lack of accessibility to African data from which AI to the local context can be developed. There is currently an asymmetrically low development of AI for the African context from African communities for the rest of the world.

Arguably AI can democratize access to information about politics, healthcare, and education. But how can we assume that an AI tool is democratic, when we already have evidence that AI can be biased?

Let’s consider the development of television in the Global South. The Global South has for the most part had access to local and global TV for at least a decade now. In the early TV era people in the Global South mainly had access to TV channels screening Western movies, Western news, all made from a Western perspective. This inevitably led to a whole generation influenced by Western media due to the disproportionate Western monopoly early TV channels. Is this how we want to go forward?

The De-Colonial Solution

The lack of focus on African contexts (among others) in AI research, development, and governance, along with limited accessibility to African data for local AI development, underscores the need for a de-colonial approach to develop AI that includes African developers and addresses the legacies of colonial wealth and power asymmetries. The de-colonial movement seeks to challenge these asymmetries of power and wealth in the AI space, advocating for the development of AI technologies that truly serve the needs of all communities, particularly those in the Global South. This entails serious efforts by local communities in Africa and the Global South to ensure that they can be heard in the development process.

First of all, de-colonial AI theories support localized AI systems, developed in the Global South, for the Global South countries. Local education programs such as the African Master’s in Machine Intelligence must increase substantially in order to create the human infrastructure necessary for the development of technology and empower the otherwise unskilled workforce to actively contribute in this field. Nations educated in AI will also help reduce their dependency on the West, leading to a more equal world. Ultimately, this approach emphasizes a dignified approach where resources are put forth for communities in the global south to decide their own AI future.

AI governance laws in the global south are underdeveloped, leaving open holes for big tech companies to exploit data, privacy, or even human rights in some cases. De-colonial AI governance entails that local communities and global law should aim to reflect the ethics, values, historical contexts of local communities and cultures. Would have such an approach allowed for the big tech monopolization of the Global South?

It is important to acknowledge the non-western ways of life such as the Ubuntu community-centric framework. Community-centric technological frameworks prioritizes human well-being in general by fostering a diverse range of perspectives, leading to a wider variety of actions that will eventually manage societal decisions. Locals are involved in decision-making, and thus ensure that technology aligns with their values and needs at any moment, making AI frameworks sustainable in the long-run.

An example of how AI is currently being decolonized is observed in South Africa where AI is being used by surveillance companies in South Africa for digital surveillance contributing to a digital apartheid. However, decolonial organizations such as the Distributed AI Research Institute, are using computer vision tools and satellite imaging to investigate the extent to which racial segregation in South Africa affects local communities. South Africa has recently championed AI device that monitors air quality. Groups like Masakhane are emergent groups that aim to decolonize AI and science by working on developing AI systems for Africans. This is to say, a lot currently is being done in the de-colonial forefront!

Conclusion

AI’s roots in colonial asymmetries, continued data colonialism, labor exploitation, and resource extraction in the global south, calls for a reconsideration of AI development tailored to the Global Souths needs. This includes investing in research and frameworks that address the specific needs of diverse communities and working towards a future where AI is developed in a manner that is equitable, inclusive, and respectful of all human dignity.