Since its emergence, artificial intelligence (AI) has continued to play a key role in the labor markets in almost every country on the planet. New and exciting innovations in technology have been projected to greatly improve labor through the automation of tasks, with online sources claiming AI will help make the workplace easier for nearly everyone. Although this is great in theory and true in some regards, not everyone has benefitted from AI’s new involvement. Millions of low-skilled workers have found their jobs and livelihoods taken from them, as their work was not strengthened by AI but rather replaced by it. This may lead to individuals and nations which already suffer from inequality to fall even further into poverty. In attempts to mitigate this, some organizations are striving to introduce ethical AI policies and education, but it may not be enough to prevent such inequalities from existing. Although the prospect of AI may be exciting, we argue the importance of remaining realistic in terms of how AI will shape humanity as a whole, especially those who are already impoverished. Thus, in this article we argue why AI actually has the potential to make national-level income and global inequality worse.

What does economic inequality mean for society?

Most people can agree that economic inequality between groups of people within modern day society is not a good thing. To name a few reasons, economic inequality undermines the fairness of the economic systems themselves and it gives wealthier people a questionable degree of control over the lives of others. Since the 1980s this steady rise in economic and global inequality has caused members of society, researchers, and politicians to become growingly concerned. Because those who find themselves on the lower ranks of the social ladder are not always able to make use of rising opportunities and often get left behind. As a result, many people start off at a disadvantaged position from the day they are born. Whereas, those that are in a more advantageous position continue to benefit disproportionately. When the majority of people – more so in certain parts of the world – suffer from economic and social stagnation, inequality can pose a real threat to the progress of individuals and to entire countries. With AI’s potential to amplify this effect through the automatization of labor, society and policy makers alike need to be aware of what implications AI can have on income inequality on both a national and global scale.

Yet how exactly does this occur? New AI technologies already are and will continue to revolutionize key industries through high-tech means such as automation. To illustrate the potential for manufacturing, one of the most meaningful impacts of AI-powered process automation is likely to be a significant reduction in the production time and cost of goods– making many products cheaper and faster to produce while simultaneously eliminating human error. The productivity gain and increased efficiency mean lower prices but also increased economic growth, at least for the multinationals and developed economies leading this technological charge. However, there is a dark side that comes with advances in AI, namely that there seem to be winners and losers in the race for increased productivity and efficiency. In this section we argue that the increasingly automated and AI-powered society has played its role in contributing to economic and global inequality.

How the low- and middle class- labor market is affected.

When looking at which countries are heavily investing in AI, the United States sticks out as one of the clear front runners. But does increased productivity and efficiency necessarily lead to economic growth and prosperity? Not necessarily, as there are a number of factors that contradict economic growth as a result of AI, a prime example being economic inequality. The United States serves as an example to analyze the effects of AI on income inequality.

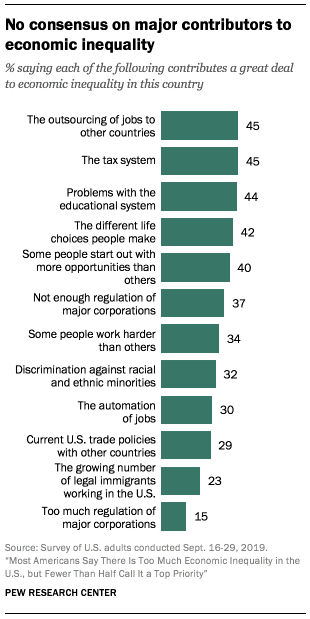

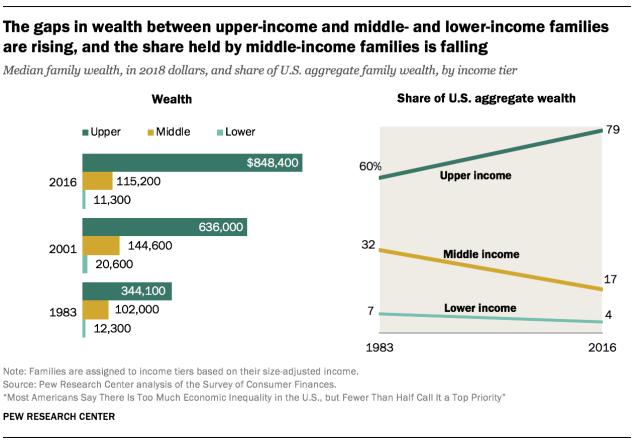

Over the last few decades, the lower and middle classes in the U.S. have seen their fortunes steadily decline. Higher-skilled workers and upper-income households, on the other hand, have seen their wealth increase in comparison. Thus, the economic inequality – whether measured through the gaps in income or wealth between richer and poorer households – continues to widen between these groups. One could think of a variety of factors that could serve as possible explanations for this trend. Many Americans, for example, see outsourcing of jobs to other countries, the tax system and the educational system as major contributors to economic inequality in the United States.

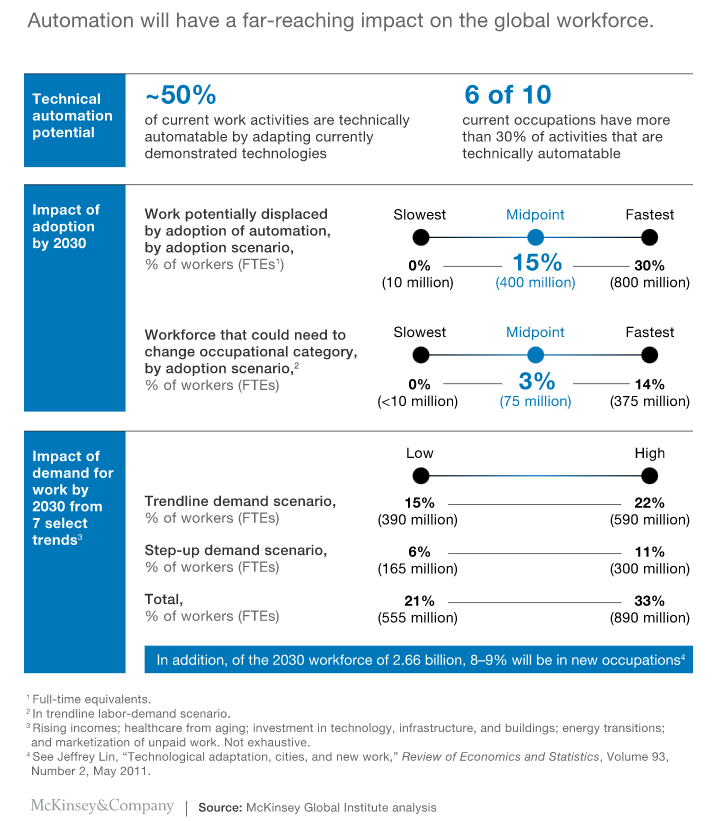

However, according to a report published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, AI and particularly automation have been the primary drivers of income inequality in the U.S. over the past 40 years. How so? By displacing jobs and directly depreciating wages of middle to low skill workers. What could one envision when they think of AI replacing a job? Well, think of a factory worker who day-in day-out performs the same repetitive tasks. This is a prime example of where AI and automation can swoop in to replace assembly line workers to make processes more productive and cost efficient. But how does this effect play out when these AI applications spread out nationwide? In a study by Acemoglu and Restrepo, Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor, the authors found that from 1990 to 2007 adding one additional robot per 1,000 workers reduced the national employment-to-population ratio by about 0.2 percent. Moreover, they found that the percentage of job displacement is significantly larger than the new opportunities that arise as a result of increased automation. From 1987 to 2016 in the U.S., displacement (loss of jobs) was 16% while reinstatement (new opportunities) was only 10%.

“There are major distributional implications,” Acemoglu says. When robots are added to manufacturing plants, “The burden falls on the low-skill and especially middle-skill workers. That’s really an important part of our overall research [on robots], that automation actually is a much bigger part of the technological factors that have contributed to rising inequality over the last 30 years.”

Daron Acemoglu, author of Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor and Tasks, Automation, and the Rise in US Wage Inequality.

Not only has automation displaced jobs but it also directly affected the wages of low to middle skilled workers. Much of the changes in U.S. wage structure, according to the paper Tasks, Automation, and the Rise in US Wage Inequality, were caused by companies automating tasks that used to be done by people. Specifically, the report claims that 50% to 70% of changes in wages since 1980 can be attributed to wage declines among blue-collar workers who were replaced or degraded by automation. Acemoglu and Restrepo also found that the increased use of robots in the workplace lowered wages by roughly 0.4% during the same period that automation displaced workers. As said by Acemoglu: “We find negative wage effects, that workers are losing in terms of real wages in more affected areas, because robots are pretty good at competing against them.”

In contrast to this, worker groups that were not displaced from their tasks, such as those with a postgraduate degree, enjoyed real wage gains. Since the 1970s, the growth in income in the United States has largely skewed to upper-income households. Simultaneously, the middle class – which made up the majority of Americans – continues to shrink. Thus, a greater share of the aggregate income is going to upper-income households and the share going to the middle- and lower-income households is steadily declining. This trend has been heightened in the last century as the wealth gap has grown sharper and continues to grow rapidly.

It should be noted that advances in technology have not always been the gloom and doom for low-skilled workers as many think it is. From the 1960s to the 1980s, advances in technology largely benefitted the lower and middle classes as it brought about new job opportunities that suited and complemented their skill levels well. However, since the 1990s workers saw those benefits depreciate as they started to feel the effects of job displacement and watched as new opportunities favored the high-skilled workforce.

Today the effects of economic inequality have actually worsened as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. Multiple technology manufacturers reported increased demand for their bots and AI solutions since the start of the pandemic. As many lost their jobs and entire sectors stagnated, the pandemic vastly accelerated automation, remote work and the technologies needed to make sure businesses could continue without large groups of workers on location. This ‘turbo boost’ for adoption of technologies, as said by Christopher Mims for The Wall Street Journal, could further displace lower-wage workers as the means to continue processes without workers on site have entered the picture.

AI, automation and the economic inequality in developing countries.

The trend for technological change to replace routine tasks, such as in manufacturing and other low-skilled labor, is set to continue. However, there are further implications of shifting towards an AI society – where low-skilled jobs are replaced – than just economic inequalities within nations. Namely, advances in AI threaten to completely disrupt the economic model underpinning the development of countries that disproportionately rely on industries that are most vulnerable to AI and automation (i.e., where jobs involve repetitive work or manual labor). This stands to worsen global inequality because as developed nations get richer by benefiting from advances in AI, the poorer nations could actively be pushed backwards as a result.

To date, robots have replaced well over half of the jobs in the car- and other related industries. Moreover, AI enabled systems are also leading to significant job losses in administrative functions such as in banking, health, insurance and accounting. These are examples of roles that had been largely outsourced to developing nations such as India, Vietnam and South Africa. Significant job losses have occurred all over the world as a direct result of advancements in AI, however, the greatest share has clearly been lost in the developing world. To illustrate, developed economies that previously outsourced their labor to developing countries are likely to turn to AI-driven solutions. Thereby replacing their factories in developing countries with cheaper, more efficient alternatives to human labor. As this shift to AI and automation will likely not be gradual, developing economies may face huge socio-economic risks as they cannot adapt their welfare and economic support nets quick enough. Thus, a human cost may be seen in the form of mass layoffs as many multinationals replace their factories at the same time. So while developed economies profit from the reduced cost to produce goods and services, developing economies risk mass unemployment and welfare crises.

Furthermore, since October 2021 it has been reported that 44 countries have their own national AI strategic plans. These countries also include developing economies such as China and India, which are key players in progressing national AI plans for the developing world. However, when scored on the preparedness of countries when it comes to using AI in public services, the lowest-scoring regions are developing countries in regions such as sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and South Asian countries. This doesn’t come as a surprise as the developed world is in a far better economic position to make larger investments in the R&D that is needed for the advancement of AI capabilities and models. In contrast, countries in the developing world have far more pressing issues to attend to before they can allocate a sufficient budget for AI development. Many developing nations have to worry about basic educational, sanitary, healthcare and food provision needs, which take clear priority over investments in tech. Thus, with certain players being able to expend vast sums of money on the advancement of AI, whilst others cannot, AI stands to further widen the digital divide that is already present between the developed and developing world.

Is all hope truly lost? Some hold a more optimistic view.

Despite all of this however, some believe that the potential negative effects of AI in terms of the loss of jobs are not so dire. In fact, the World Economic Forum estimates that tech will create 12 million more jobs than it replaces by 2025, thereby making such automation beneficial in terms of providing sufficient employment for low-income workers. They argue that with the development of AI technology, rather than replacing humans outright, will create new jobs which require cognitively-challenging human abilities which (currently) cannot be replaced by automation. This could allow for low-income workers around the globe to obtain higher-paying and safer jobs, helping both class inequality and global economic inequality. With the help of wealthier nations, those in need can receive help in terms of education for skilled jobs, the implementation of AI infrastructure in their own nations, and assistance from their own AI. The organization ‘AI for Good’ for instance has goals to ensure the fair and ethical incorporation of AI all throughout the globe, and other organizations that strive to do the same. One programme as rolled out by MIT in 2005 provides laptops and technical education to children in over 30 countries, to provide education and thus improve economies. Therefore, with such help, it may be the case that impoverished nations will eventually be able to participate in the AI race themselves.

Moving on to the topic of losing jobs, some argue that AI in the workforce will primarily assist humans rather than replace them. Take the field of healthcare for instance: due to the high degree of communication and human contact involved, the likelihood of nurses being replaced by AI is very slim. Rather, the field would in fact benefit from the incorporation of AI which could replace menial, repetitive tasks, therefore making work more efficient for both employers and the employed.

Although this optimistic take is ideal, and some do indeed benefit, it is seemingly negated. First and foremost, although forecasts on the potentially growing labor market are valuable, examining the known history of many jobs being lost provides a perhaps more realistic expectation. Additionally, even if these new jobs are indeed created, it will not necessarily make them accessible to low-income workers. This is due to the fact that such new jobs will most likely require specialized training, something that requires time and money- something in which low income people and those in impoverished nations may not have. This begs the crucial question: how will such training be made possible? Sadly, it simply may not be. Although this critical issue is acknowledged by policy makers and non-profit organizations alike, the logistical and financial organization on such a grand scale is not entirely feasible. This is exacerbated by the fact that many corporations simply favor automation over human employees to save funds on tax breaks and wages. Therefore, they are not necessarily personally incentivized to ethically contribute if left to their own devices. Finally, even if a significant number of impoverished individuals were educated, there is no guarantee they will remain there and contribute economically. It was found that highly skilled workers tend to prefer to live in more developed cities, meaning training may indeed help individuals but not necessarily improve the national economies on a grand scale.

Offering a helping hand: can global equality be achieved through the generosity

One reason in which nations are behind others economically is due to the fact that all resources are dedicated to achieving a basic standard of living, such as sanitization and healthcare. Although people in impoverished nations may suffer more from loss of jobs, does this mean that AI is bad for them overall? It may not. Although poorer nations may not have the infrastructure for AI themselves, generous organizations are able to assist them in not falling further behind. The idea is that even if such nations lack the AI infrastructure themselves, wealthier nations can offer assistance using their own. In turn, this would allow for such nations to focus on building their economies and labor markets to eventually include AI, rather than falling further behind because of it. An example of a nation which was assisted using outside AI is Nepal; after a 2015 earthquake leading to the displacement and death of many Nepalese people, over 4000 private organizations and NGOs offered both physical aid and AI resources. Data collected through geological surveying was used to determine areas in which were safe or unsafe to reside, with the purpose of providing guidance as to where people should relocate to in order to prevent future disasters. Unfortunately however, the realities of such humanitarian efforts do not always go as intended. Concerning the situation with Nepal, although safe and unsafe habitual zones were identified, 52% of people identified as living in an unsafe zone had to remain there, and only 6% of settlements that were to be made safe were completed. This occurred as although numerous organizations offered help, technical difficulties, communication barriers between organizations, and other factors stalled or halted efforts. Therefore, simply offering help to such nations in need is not a trivial task. It may take the incorporation of their own AI infrastructure to be included in the benefits of such new technology. In the meanwhile, it unfortunately appears that they will continue to suffer.

A final word.

To conclude, advances in AI continue to have widespread effects on the labor market all over the world. There are not many sectors that remain totally untouched and there are some that are being completely transformed as a result. Low to middle skilled workers have witnessed the effects this can have on their working lives, income and livelihoods. Entire countries are struggling to keep up and risk being left behind as their economic models depend on the industries where AI is most prevalent. Thus, economic inequality as a result of AI and automation is still growing wider. As wages for these workers continue to decline and new opportunities are not readily available to them, there is no sign that the gap in economic inequality will close. Although it is true that humanitarian efforts and governmental policies alike are being established to mitigate such effects through educational outreach and assistance, it may not be enough. This is as solving economic inequality is no menial task, and there are millions of people who may be effected. Admittedly, it is easy to focus on the positive of AI’s effect on the economy and labor, as it has indeed improved some aspects for wealthy nations. Through strict governmental policies and regulations, it may one day be possible to help those in need and allow everyone to benefit from AI. Until then however, we must keep in mind those who are negatively effected, and attempt to pressure both governmental and corporate agencies alike to make serious attempts in solving the issue.