It finally happened; we’re living the data nightmare.

In a world where money buys the means to influence the beliefs of individuals via personalized ads curated by powerful algorithms, John Stuart Mill’s idealized marketplace of ideas is no longer a free market.

Specifically, in the digital marketplace of ideas, online behavioral advertisement (OBA)—using behavioral targeting technology to offer ads based on a user’s virtual identity—has been wielded to sway others’ feelings, beliefs, and actions a number of times in the recent past.

The result of this algorithmic screening: scandals, like Cambridge Analytica; 87 million American voters covertly robbed of their data and an unfair, not-so-democratic election held in the country in 2016. At the time, just as the scandal blossomed in the United States and United Kingdom, headlines of a darker truth rapidly made it around the globe: they’re not the only ones.

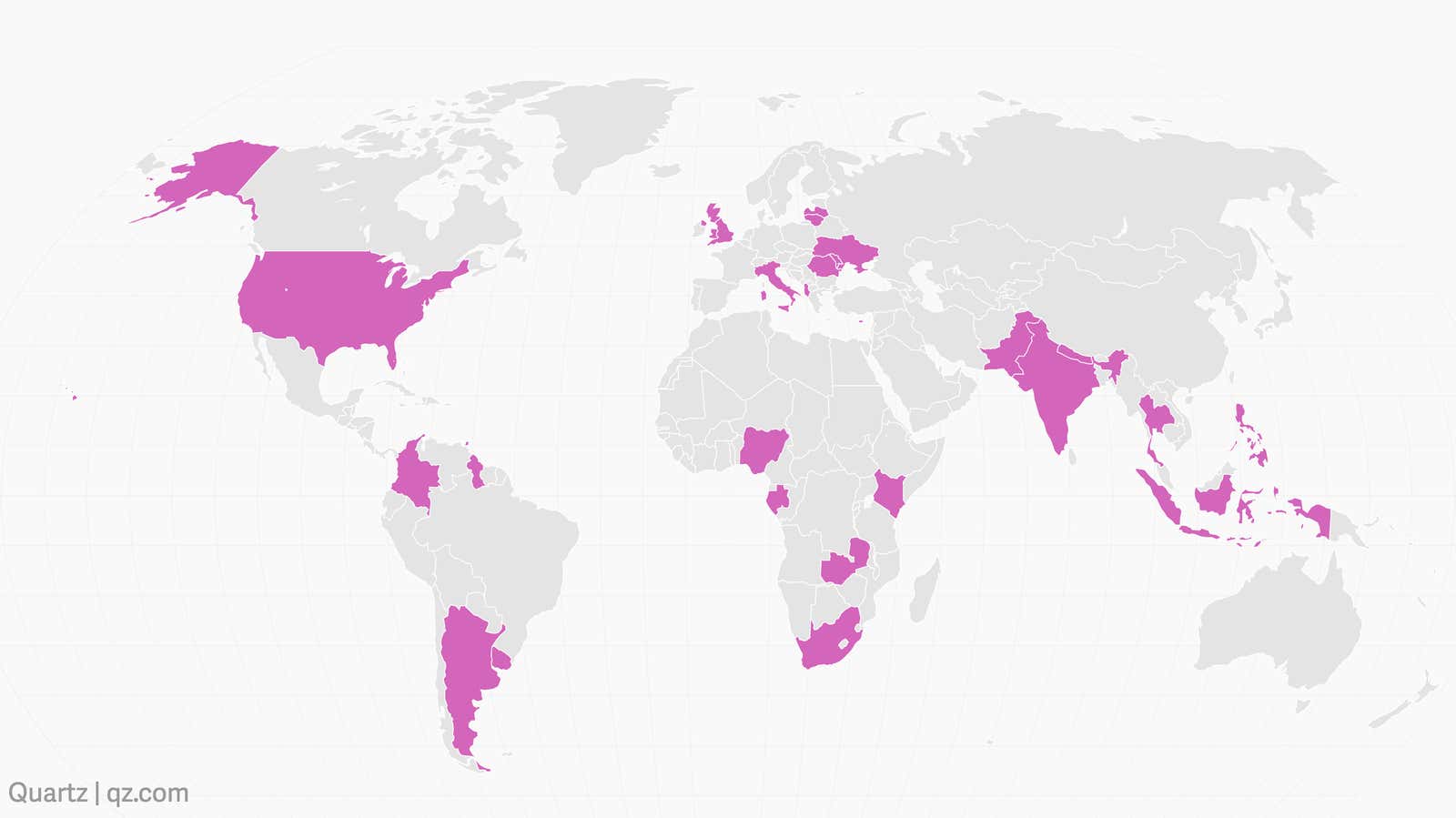

Nigeria, Argentina, India, Kenya, Czech Republic, and many more—as the involvements of Cambridge Analytica came out of the woodwork, the success of microtargeting in electoral manipulation has only served as a Litmus test for the severity of the risks associated with this practice.

And as this controversy has attracted more scrutiny, we have only come to find more evidence of others misbehaving with their OBA toys: On the sidelines of the U.S elections, Russia was another (independent) stakeholder playing with this technology, stoking extremism and lighting a social fire with the static of the polarized American people.

Yet, perhaps this is just the tip of the iceberg; as artificial intelligence (AI) continues its exponential evolution, personality-profiling algorithms become infallible, and generative AI becomes the world’s best content creator, manipulative marketing will only continue to expand its arsenal. After all, if today’s technology can propel the potential of personalized ads into fueling not just Cambridge Analytica’s achievements but also Russia’s attempts to influence political elections with psychographics, one can only imagine a somber future.

Therefore, in its current state, OBA doesn’t just threaten our ability to think and act freely; it’s a Chekhov’s gun pointed at democracy. As such, targeted ad campaigns should be offset by a balancing factor: human critical thinking and reasoning. To give the online populace a chance to escape the puppet strings of advertisements, targeted ads should demonstrate greater transparency—visible company names, labels indicating the campaign’s target groups (e.g. gender, location, etc), the number of individuals reached, and all variations of the ads shown to their users.

Amongst a variety of benefits, doing so would play into the concept of creating conscious consumers. According to V. Danciu, a researcher at Bucharest’s University of Economic Studies, the conscious consumer is that who behaves responsibly in economic, social, and environmental sustainability contexts—one who is able to identify, understand and abstain from unnecessary or unwanted consumption: a critical thinker.

Danciu believes that the greater the conscious consumer’s awareness of the intentions and methods of advertisements, the lower the likelihood of manipulation. A belief likely closer to reality when examining the literature. A study presented by the International Journal of Advertising reached the conclusion that compared to the standard disclosure in ads, displaying more detail, such as the identity of the sponsor or insight into the sponsorship’s business model, leads to lower credibility of misinforming sources. Even better, if individuals are aware of the data used to target them and its relation to their personality, this increases the detection rate of microtargeting by an additional 26%, as reported by the Max Planck Institute on Human Development. Conscious consumption elicited by transparency is real, and it doesn’t demand the advertiser’s social security number or balance sheet.

In spite of this, some advertisers think otherwise, arguing that ad performance will suffer as a result of these less opaque practices. Although the claim has substance, it comes in favor of transparency; multiple studies suggest that it’s only when consumers believe their data was unacceptably obtained that the effectiveness of the advertising suffers. Therefore, advertisers making acceptable usage of user data shouldn’t have cause to fear for their ad’s performance. Not only that, platforms will be incentivized to build user trust as this is shown to increase the efficacy of advertisements. This means that improved transparency measures actually may provide additional benefits by discouraging invasive advertiser behavior.

In fact, more disclosure from these companies won’t so much as hurt their revenue as it would boost it. Currently, a range of research on public perception demonstrates that microtargeting practices are to the online consumers as what the candy-offering stranger is to our children: creepy, intrusive and scary. AdReveal, a tried and tested measurement and analysis framework for targeted advertisement, conveyed that increasing trust in the company can prevent this negative reception and improve the user’s experience. One accessible way to achieve this has been shown by an experiment in the journal of Communications and Research Reports; providing some explanation for the consumer’s targeting such as a broad overview of the data used to include them, significantly increases the positivity of their responses to the ad. Perhaps, advertisers have yet to learn the adage, “you catch more flies with honey than with vinegar.”

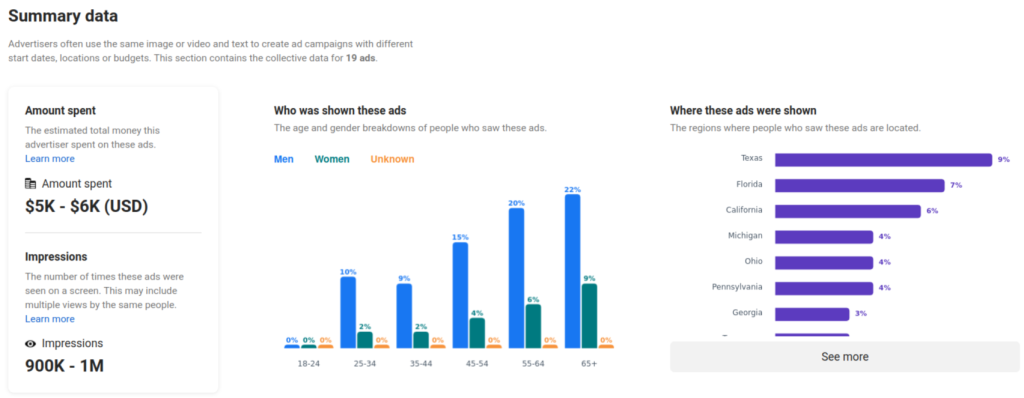

Naturally, some might argue that the big tech giants have already done enough to tackle this issue such as Facebook, Google, and Twitter’s commitment (in the wake of the 2016 US Presidential election) to provide archives of political ads run on their platforms. While these are steps in the right direction, further improvements and policies are needed—one study found numerous issues, including that “advertisers are intentionally or accidentally deceiving and bypassing these political transparency archives.” Furthermore, the transparency details within these ad repertories are unclear to the targeted users; ads don’t link to their entry in the archive, and users can’t see which of their details were used to target them. Whatsmore, given that media platforms may perceive possible conflicts of business interests with transparency measures, it’s apparent that self-regulation is insufficient and legal policies for such measures are necessary.

Trust, Transparency & Respect

With the ubiquity of OBA across the web, and the mismatch of power between advertisers and individuals whose personal details are blindly exploited, it’s natural to question the trust we place in the online platforms we interact with daily. But a better world is attainable for users, advertisers, and media platforms alike; a world centered around the values of trust, transparency, and respect.

With some of the media giants already taking some steps towards transparency by archiving advertisements for public view, the time is ripe to push the status quo a step further: We must enact policies granting users the right to know which of their details influence each ad they’re shown, and add stricter measures to verify the true identity behind advertisements.

Such changes will empower conscious consumers to be more informed about the data practices of the companies that already know so much about them, increasing their awareness about how their personal information is used. At the same time, the marketing businesses will benefit as well; as increased transparency breeds incentives for fairer data usage practices, well-behaving actors will be rewarded by the enhanced engagement that comes with establishing user trust.

A world with more visibility around targeted adverts, levels the power imbalance between data-hungry advertisers and public citizens—ultimately, creating a more equitable marketplace of ideas.

It’s not too late; it’s just time to shift from the data nightmare, into the data dream.