Introduction

.

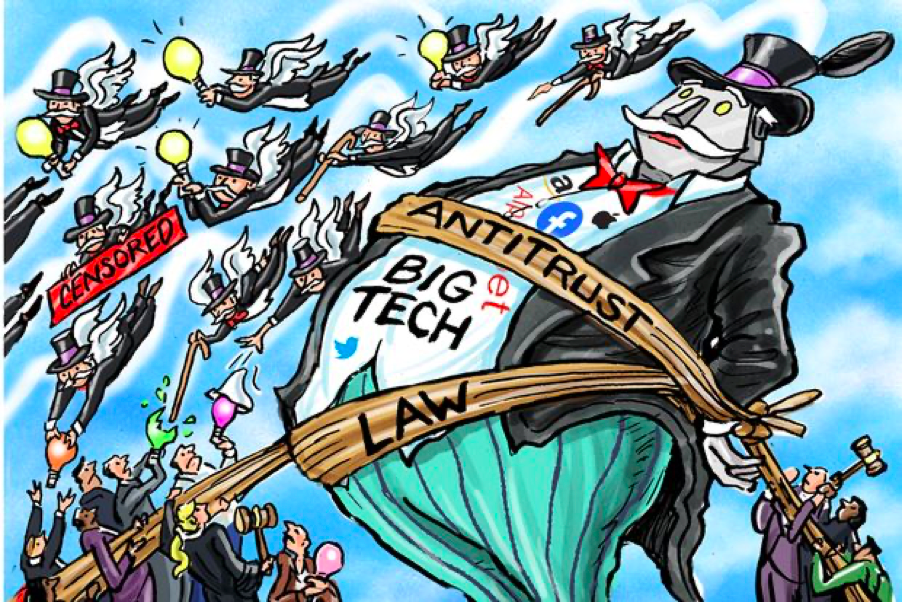

As we move towards a global economy powered heavily by Artificial Intelligence, the prevailing consensus has shifted towards the idea that data, rather than oil, is now the world’s most valuable resource. This digital economy, however, is plagued by a natural tendency towards monopolisation. In the past, companies like AT&T and U.S. Steel have had their monopolies broken up by anti-trust laws, but today, with the rapid growth of Silicon Valley, the legislature required to end this cartel is egregiously outdated and not tailored to counter the growth of monopolies in the tech industry. The monopoly on data accrued by GAFA has serious implications for wide aspects of what democratic societies have held sacred for thousands of years. By looking at notions of ‘Truth’, at elections, polarisation and equality, I will first explore the ways in which today’s big tech monopolies threaten democracy, and then examine how and why we are powerless to stop it.

It seemed at first that the advent of social media was going to usher in a new age of democracy. In 2010, the Arab spring, a series of anti-government protests, uprisings, and armed rebellions that spread across much of the Arab world was initiated largely with the help of social media. Indeed, partly as a result of this, TIME magazine honoured Mark Zuckerberg with Person of the Year 2010. But following a series of high-profile electoral scandals like the Cambridge Analytica fiasco and the Mueller probe, the CEOs of tech monopolies, once regarded as capitalist heroes in our liberal democracies now seem to play out more like autocratic villains.

So what went wrong? Can we even fix it?

Before moving onto the ways in which Big Tech damage society, the problem is best framed as an economic issue. Social media companies like Facebook didn’t set out to ruin democracy. The reality is that negative consequences to society are ultimately collateral in a meticulously-oiled profit driven machine. Social media revenue depends almost entirely on engagement. Without engagement, they can’t run adverts; as Roger McNamee puts it:

If you take out hate speech, disinformation and conspiracy theories, engagement with these platforms goes down – and with it their economic value

Roger McNamee, Wired

Nonetheless, the lack of legislation allows them to get away with inadvertently damaging society. Tech companies are particularly profitable because they are not responsible for the cost to society. And, while these companies have recently tried to police themselves, this raises a serious problem: do we really want the technology monopolies to be in charge of their own regulation? Does it not raise serious questions about power when Fortune500 companies behave and appear like nation states? Indeed, Microsoft recently pledged $500 million to improve affordable housing in Seattle – a job that should be done by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development

.

A divided society: Political Polarisation

.

One of the growing threats to democracy arising from the growth of social media is political polarisation. 2020 has seen this polarisation come to the fore with the US election catalysing the cultural divisions in the country. There is a mainstream consensus that AI is one of the driving factors in this polarisation, exploited by companies like Facebook who use intelligent algorithms to show users increasingly polarised content to increase engagement. In May of 2020, The Wall Street Journal gained access to an internal presentation from Facebook HQ, quoting executives as stating that:

‘Our algorithms exploit the human brain’s attraction to divisiveness … if left unchecked, [Facebook would feed users] more and more divisive content in an effort to gain user attention & increase time on the platform.’.

The executives at Facebook understand that they can use machine learning to predict the content that users are mostly likely to engage with. Unfortunately, this content tends to be ‘more extreme than average’, as noted by researcher Brent Kitchens, discussing his research with Wired in 2017. The WSJ also quoted Facebook executives as saying that ‘64% of all extremist group joins are due to our recommendation tools’, and that ‘Our recommendation systems grow the problem.’ What is perhaps even more worrying is that a 2015 Michigan University study suggested that that more than 60% of Facebook users are entirely unaware of any curation on Facebook at all. It seems that we users are unaware of this process.

Yet it is not just the recommendation algorithm at Facebook that drives this divisive content, the problem appears to be more inherent. Kitchens points out that [compared to a site like reddit] Facebook requires reciprocal friendship, which encourages a feed of like-minded people and reduces the chance of seeing opinion-challenging content. Facebook’s algorithms create feedback loops that perpetually show users what it thinks they want to see. Indeed, a recent study found that deactivating Facebook for the four weeks before the 2018 US midterm election reduced both factual news knowledge and political polarization.

And while Facebook have started to make strides in fighting polarisation, a lot of the targeted measures raise separate questions about free speech. Balancing the democratic principle of free speech and the democratic imperative to fight division is an impossible act.

We can think of this polarisation problem as the confluence of two very concrete aspects of human existence today.

The first is human’s propensity for dimensionality reduction. Jeremy Harris of Quillette invites us to consider the brain as a biological computer. Human experience is based largely on the two competing elements of perceptual bandwidth: that we are faced with a physical limit on data storage, and that the information that we are exposed to vastly exceeds this limit. In a parallel to the way AI solves this same bandwidth conundrum, our brains effectively perform an analogous process of data compression.

“Rather than remembering each and every noise that two politicians made during a political debate, for example, our brains distill the sounds they hear down to a reduced representation of the exchange, that we end up retaining as a “take-home message”, “lesson,” or “memory”, depending on the context. And these form the basis of our opinions.”

Jeremie Harris, Quillette

This cognitive process is especially problematic when combined with the second factor, the advent of the internet; in today’s world, the amount of information available is truly staggering: the human brain was not built to cope with this mountain of data. When in 2009 Google began to personalise search results, the notion of a standard google was over. Yet the Algorithms that were intended as putative user experience improvements, driving up the convenience and quality of search-results, have had some unintended negative consequences. When we consider that people today derive a huge portion of their knowledge of current affairs from Google and Facebook, there is something incredibly dangerous about ‘tools’ that perpetuate a human tendency towards confirmation bias. These digital chickens have come home to roost with deadly consequences in the USA. As the country gets orthogonalised more and more on a conservative/liberal axis, a culture war is brewing, and this has so far erupted in numerous high-profile instances of violence.

Beyond the violence of the culture war, polarisation also presents serious problems for the democratic process because it makes bipartisan compromise very difficult, this in turn seriously damages the effectiveness of governments ability to veritably act. This was exceptionally clear when the debates over how to deal with Brexit consumed the entirety of UK politics for over 3 years.

But polarisation has another more profound impact on democracy, perhaps an impact that transcends even democracy. In today’s age of Fake News and disinformation, the idea of ‘Truth’ is losing its objectivity. Google, once a beacon of colloquial factchecking is now effectively a personalised fact checker, giving different ‘Truths’ to different users. Thus, Truth becomes relativised and subjective. Each side of a dispute now believes in its own infallibility.

.

If we are all ‘right’, then what is ‘Truth’?

.

We should note 4 facts of this new reality:

- The overload of information available on the internet means that there is almost always a source, valid or not, that supports one side of an argument.

- Google is now more likely to suggest these articles to the people that want to see them,

- Google and Facebook are significantly less likely to show the user sources conveying alternative opinions.

- There has been a massive decline in the use of traditional journalism with 62% of U.S adults getting their news via Social Media – a domain which is legislated by libel laws and legally forced to keep a basic level of truth.

This means that while objective truth may still exist, anyone with access to the internet has access to controversial opinions, a tendency to support those opinions and the sources to back them up. Therefore, the rise in conspiracy theories within the political mainstream is not in fact surprising. Where before we might have decried proponents of theories like Q-Anon as eccentric nut jobs, it is harder now to criticise those so resistant to their own fallibility when the internet so powerfully gives them to tools to be brainwashed with ease.

However, the deterioration of Truth has not merely affected the civility of political discussions at the thanksgiving table, indeed, in 2020, the loss of truth has had deadly consequences. Studies have shown that disinformation campaigns such as those that connect 5G to the spread of Covid has directly increased the death toll in many countries. A similar thing has happened in the domain of climate science, where Facebook was used to spread ads promoting climate change denial science.

Of course, Facebook has attempted to fight the spread of misinformation by offering fact-check warnings on viral posts, however, this solution suffers from the same problem as their solutions to fighting polarization:

Balancing the democratic principle of free speech and the democratic imperative to fact-check lies is an impossible act.

If the barrage on Truth that arises from algorithmic negligence from Big Tech can be considered accidental, then there is a far more nefarious assault on truth that is very deliberately sewn by agents of disinformation.

.

Democratic Elections require Truth

.

When truth becomes equivocal, anti-democratic agents have the tools to damage democracy. This came into fruition in 2016 with the spread of false stories during the US Presidential Election, when Russian agents used Facebook and Twitter to help elect Donald Trump and generally sow distrust in American democracy. Similarly, by going through the poorly legislated sphere of social media, Cambridge Analytica were able to have a huge impact on the outcome of the Brexit referendum, spending millions of pounds posting fake information through targeted facebook ads, thereby circumventing UK laws relating to electoral spending. The reality is that algorithmic features of online platforms encourage clickbait headlines and emotional messages, and that they those seeking to damage democracy can reach wide audiences using paid trolls and bots.

Hypothetically, legislation would force social media executives to prevent the spread of misinformation. Indeed, Facebook’s hiring of a large number of content reviewers, and Google’s implementation of machine learning to help in removing extremist content, suggest that companies are beginning to acknowledge their responsibility in fighting the spread of extremist ideas. However these interventions fail for 2 main reasons.

- Tasks that may seem trivial to many—detecting online bots or trolls, categorizing content as real or fake news, and deciding what is “obviously illegal”— are notoriously difficult to implement.

- Because their power gives them prerogative to self-police, every time there is pressure on companies to either eliminate a bad actor like Alex Jones, or to take down a piece of bad information like something on the pandemic or Trump’s “looting shooting” post, they take down the bare minimum.

But it’s not only established Western democracies that suffer from the dangers of social media. ISIS, for example have been using Facebook very successfully to recruit agents to their cause, taking advantage of the ease of reaching so many people and the efficacy with which emotional messages are spread through friend to friend contact. Indeed, ISIS proficiency with social media is such that Wired made the following claim:

Today the Islamic State is as much a media conglomerate as a fighting force.

Brendan I. Koerner, Wired

While in Cambodia, the country’s authoritarian prime minister has been using Facebook to manipulate public opinion and strengthen his hold on power.

After facing criticism from Journalist Maria Ressa for the way he had used Facebook to spread outdated news stories as propoganda that justified calling a national state of emergency, Filipino President Duterte subsequently weaponised Facebook again, creating thousands of fake accounts to incite a national hate campaign, bullying Ressa into silence.

Facebook even admitted to their platform having helped to incite violence in Myanmar, with fake stories widely spread such as the 2014 story of a Muslim man who had apparently raped a Buddhist woman, directly sparking an upsurge in attacks on Rohingya muslims.

.

Inequality: When the rich get rich, the poor get poorer

.

The power that tech oligopolies wield is not solely dangerous to democracy because they are unaccountable for the damage they do to society. The consequent economic inequality inherent in the formation of ultra-powerful tech conglomerates is a danger in itself.

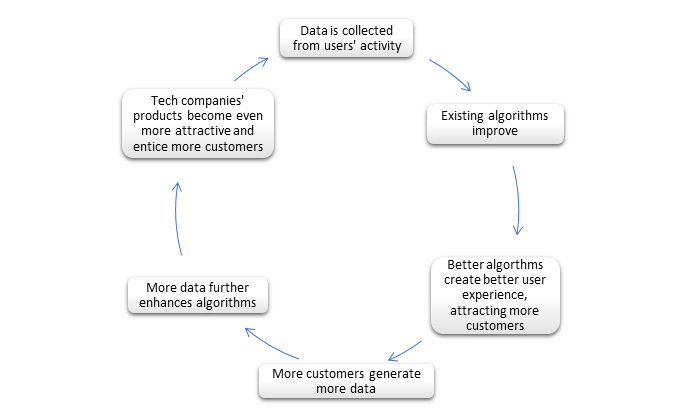

Big Tech power concentrations arise because intelligent algorithms fed with large datasets lead to better user experience and improved features. This, in turn, attracts a larger user base. More customers accordingly generate more data, refining the original algorithms to improve products, perpetuating a cycle of expanding market control. in 2018, this process saw the Duopoly of Facebook and Google reach an 84% share of new advertisement revenue, once the domain of a plethora of private press outlets. Indeed, Apple’s annual revenue is so large that when compared against (Tax) revenues of World States, it ranks 23rd, ahead of major economies like India, Belgium and Mexico. Scientists now warn that rising inequality can trigger resource collapse and poverty. True democracy absolutely depends on power being in the hands of the people, true democracy absolutely depends on the threat of revolution being credible. Such massive inequality inherently prevents the people from having the resources to keep their government in check.

Whilst Big Tech yields great power at the peak of their success, it is also valid to point out that these tech giants are perpetually subject to ‘disruption’. MySpace was once the world’s largest social network and Yahoo once Fortune magazine’s top search engine. Indeed, smart bots could soon threaten Google’s core search business. However, even if GAFA in 2021 are able to be replaced by giant competitors, we have to see any formation of ultra-powerful tech conglomerates as an affront to democracy

.

Solutions? Regulation, Regulation, Regulation

.

There seem to be only two solutions to this problem: regulation in the form of anti-trust laws and regulation in the form of industry standards. Indeed, when it comes to regulation, the tech industry is a noticeable exception to the laws that generally govern industries in democracies. When the growth of the automotive industry began to start causing deaths and injuries worldwide, the legislation arrived, and now every car on the street is subject to intense (and expensive) safety approval testing. Even giants of the fashion industry are being slowly forced into providing workers with safe working conditions and not pumping toxic waste into third world water supplies. But when social media is heavily linked to an increase in suicide in the U.S, or when Facebook admits to helping drive genocide in Myanmar, there are no legal repercussions resulting from their corporate negligence and failure to protect both users and society.

What links the slowness in prosecuting Primark over child exploitation, and the legal impunity of Zuckerberg and co. is the inherently global nature of international companies, transcending the legal boundaries of country-specific legislation. If there is any hope for legally challenging the tech powers, it is a lone 2014 case in the European Court of Justice who held that Google Inc. is directly subject to Spanish data protection law. This however, pales in comparison to the litany of legal challenges in the last decade that Big Tech companies have wriggled out of like water off a duck’s back.

Therefore, both suggested solutions really depend on whether or not companies like Facebook and Google are willing on their own to decide to save democracy at the cost of losing revenue. Facebook have in the last week agreed to stop recommending political groups. However, there is a long way to go before more radical ideas like taxing data and giving human’s data rights as human rights ever become a reality.

.

Conclusion:

.

Ultimately, this author concludes that big tech is inherently incompatible with democratic ideals. Their problems are intrinsically cultural and by no means accidental. We know that Facebook’s bottom line is driven by painstakingly engineered hate speech, disinformation and conspiracy theories. Google and Facebook are very deliberately bringing an end to the age of traditional journalism. None of this is a secret. When we regularly see reports of exploitative practises at Amazon and Uber, we understand that the culture of Big Tech is one that demands unprecedented convenience to its customers, accompanied by complete negligence towards the negative impacts that their services have on society’s external stakeholders.

And yet, we as a society, seem both powerless and reluctant to halt the relentless march of the tech giants. As Yuval Noah Harari puts it:

Ordinary humans will find it very difficult to resist this process. At present, people are happy to give away their most valuable asset — their personal data — in exchange for free email services and funny cat videos. It’s a bit like African and Native American tribes who unwittingly sold entire countries to European imperialists in exchange for colorful beads and cheap trinkets.

Yuval Noah Harari – 21 Lessons for the 21st Century

Hundreds of years since Europeans colonised and ravaged the indigenous new worlds, international inequality still remains egregiously persistent. Reflecting on this offers a pessimistic outlook on the future of digital equality in the next century. When the world’s most powerful judicial body – The United States Senate – fails to adequately punish Facebook for allowing Cambridge Analytica to illegally change the outcome of US democracy, it seems that it is too late to halt the power of Big Tech. Pandora’s digital box has been opened and one wonders whether the only way back is revolution:

Just as communism emerged as the response to deteriorating living conditions among ordinary workers, it is likely that the advent of AI will create new ideologies and movements of an unprecedented scale.

Sukhayl Niyazov, Towards Data Science