Why deepfake technologies may have unprecedented implications for society, justice and politics, and why their development and open-sourcing must be reconsidered.

Imagine this: You are scrolling through your newsfeed when suddenly a video catches your eye. The video shows Barack Obama, former president of the United States, addressing the public in what seems to be a formal address. You are intrigued. You click on the video expecting a grand announcement by the former president, but what you see is quite something else. In the video, Obama expresses several controversial opinions and insults his successor Donald Trump, stating how the then-sitting president is a “total and complete dipshit.” At first sight, the video looks real, sounds convincing, and above all, seems politically plausible. You share it with a friend, who shares it with his, and soon everyone and their mother has seen it.

Yet, this video was not real; that was not Barack Obama in that video, nor did he make spiteful remarks regarding his successor in the public address. Instead, the video was generated using clever computer graphics and state-of-the-art machine learning.

In recent years, researchers and media outlets alike have praised the advances made in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning on their ability to do things that just a few years ago were deemed unimaginable; today, AI can help diagnose illnesses, it can generate art and it can even compose entire musical symphonies with no more than a press of a button. Yet, at the same time, it has been widely acknowledged that these same technologies may provide opportunities to those with malicious intent. For example, to impersonate someone else’s likeness in order to spread misinformation or incite societal unrest.

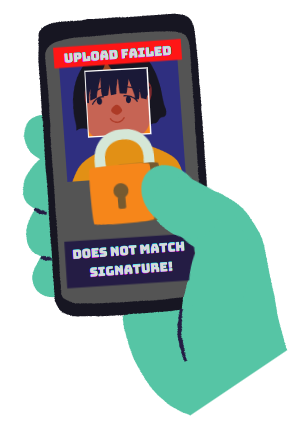

The video you imagined watching before is commonly referred to as a deepfake, a term used for images, videos or audio files which appear to be real, yet are partly or even entirely generated using deep-learning. Today, deep-learning in the form of autoencoders and generative adversarial networks (GANs) can produce persuasive counterfeit videos of people by studying large collections of headshots, to then drive their facial behavior from someone else’s movements, allowing an actor to effectively puppeteer someone else’s likeness. Couple this with the reach of social media and you have a technology that can spread convincing fake videos of people saying or doing anything to an audience of potentially millions of people.

In this article we will shed light on the implications surrounding the development of AI-powered deepfake technologies and argue why they may cause considerable harm to the societal and political sphere in the near future, despite only having a minor impact on society and politics thus far. In the sections that follow, we argue that deepfake technology can easily be weaponized, has many political and social misuses and has the potential to disrupt what is seen as evidence and truth. Then, we will discuss why recent attempts to prevent and detect deepfakes will merely slow down their impact on society and why governments and platforms must instead consider tackling the spread of deepfakes at a more fundamental level; the development and distribution of these technologies themselves.

One technology, plenty of concerns

Today, a considerable number of research papers are published every year concerning the advances made in facial reenactment and deepfake technology. Yet, despite their often harmless intentions, from entertainment and visual effects to witness protection, many are worried that these same technologies may be used maliciously.

Back in 2013, the World Economic Forum already listed the spread of disinformation as one of the top 10 trends emerging in the coming year. As social media has grown in its user base, so has the dissemination of misinformation. Social media has become the perfect breeding ground for disinformation and manipulated media with the ease of sharing things with just a simple click and people often paying limited attention to the credibility of posts. Fake news outlets, articles and pictures are already circulating on social media and now this same phenomenon may start to emerge for video. Manipulated videos have recently been shared by politicians in order to push their own agendas, one example being the doctored video of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi which was reedited to make it seem like she was intoxicated. Though, this video was not as sophisticated as a deepfake, often referred to as a shallow fake, it shows the potential for convincingly manipulated videos to go viral, be used as slander and influence the political discourse. AI is already viewed as a potential threat to democracy and privacy by many in the scientific community, where one’s behaviour can be manipulated through targeted propaganda and fake news, leading to more doubt in trusted establishments. Similar concerns are now raised regarding deepfake technology; the introduction of deepfakes will not only increase the ways disinformation can be spread, but also seriously harm the credibility of individuals and organisations.

It may seem rather fun, being able to puppeteer public figures to have them say something utterly ridiculous, but deepfakes can do a lot of harm to the people they depict; and its influence reaches far beyond high-profile CEOs, politicians, celebrities. According to researchers at Deeptrace, an overwhelming majority of deepfakes online today are of pornographic nature with almost 100% of them depicting women. Women’s faces, whether that be actresses or regular people, are used without consent for pornographic videos. This kind of misuse is a threat to one’s privacy and can be very damaging to someone’s mental health, even if it is known to be fake. In the worst case, deepfakes can be exploited in order to commit fraud and identity theft and used as a tool for extortion by blackmailers threatening to release revealing deepfakes.

With the recent advances in deepfake technology, open-sourcing becoming a de facto standard and deepfake services popping up, it will become inevitable that deepfake technologies will at one point become yet another tool in the toolbox to be used by malicious parties to threaten our society, security and privacy 一 the possibilities for misuse of these technologies are endless.

Deepfakes and our perception of evidence and truth

Fortunately, the direct impacts of deepfakes have thus far remained limited, staying within the realm of entertainment and small-scale, non-consensual pornography. Whether any of the grand fears of deepfake technology will materialize will remain a matter of speculation until that time comes. However, one thing can be known for sure; the technology exists 一 a fact which on its own may have profound implications in the near future.

For decades, audiovisual evidence has been an important tool in the context of justice, law and everyday life with the underlying assumption being that convincing audio and video manipulation would be prohibitively difficult to get right; now with the advent of deepfake technology this view may be contested. As with images that can now be so convincingly manipulated, audio and video will lose their status as infallible evidence when their manipulation becomes as trivial as photoshop is today. Think of how CCTV footage could be doctored to frame someone innocent for a robbery they did not commit; or perhaps, how someone could be framed using a counterfeit audio recording in which they confess to a murder. In the age of deepfakes, the consequences of blindly trusting audiovisual evidence may be devastating.

The existence of deepfake technology would also provide a means to further materialize the so-called “liar’s dividend”, allowing the guilty to shrug off evidence as manipulated or faked. When evidence looks even remotely suspicious, people under scrutiny will have an incentive to openly point out these flaws and deny its legitimacy. With the existence of readily available deepfake technology, any video or audio that looks or sounds remotely artificial may plausibly be doubted, leading to the ability of the public to dismiss legitimate evidence of events that did happen.

The problem of post-hoc deepfake detection

It is often the case that different people propose different solutions to a problem and some argue that there are methods to prevent the harmful consequences of deepfake technology and that tempering the development and distribution of the technology need not necessarily be a part of it. Today, researchers have focused primarily on the detection of deepfakes; researchers at DARPA, Microsoft and Facebook have been hard at work to build machine learning systems to detect, flag and remove generated media automatically before anyone gets to see them. Simply run the video through an algorithm and boom, all misinformation is removed! And this idea has had some success. However, despite recent successes, the idea of fighting machine learning with machine learning is inherently flawed. To see why, we will need to discuss how these algorithms function.

Before a detection algorithm can be deployed, it first needs to learn what quirks and artifacts to look for in an image in order to identify it as a ‘fake’; that is, it needs examples of real images and deepfakes to learn from 一 and, lots of them. Yet, with every new deepfake approach published, each with its own distinct quirks and artifacts, a new detection algorithm will need to be trained or the old one updated. But, how do we get these new examples? If the deepfake generator is readily available the answer is simple; by generating examples ourselves. But, what if the circulation of this new approach has remained under the radar? Algorithms cannot fight what they have not seen.

Detection algorithms will, by definition, be on the back foot, making it such that the consequences of new deepfake technologies will be felt before anything can be done about it. In an attempt to stay ahead, tech companies have encouraged the creation of deepfakes. In 2019, along with other tech companies, Facebook set up the Deepfake Detection Challenge where they created and shared a new dataset containing more than 100,000 videos. However, as these new datasets are accessible to the general public, and thus deepfake creators, it will only be a matter of time before these same datasets will be used as fuel for generators to become even better and bypass detection.

The development of deepfake detectors will be a game of cat-and-mouse. First, some new technology is released after which methods will be devised to recognize its distinctive artifacts in order to detect it; shortly after, solutions are found to patch these artifacts and circumvent detection, and the cycle continues. In fact, this can already be seen in recent publications; today, the telltale signs of deepfake imagery, such as gazing eyes, have now long been resolved, rendering previous detection algorithms obsolete. Researchers have even built approaches to purposefully circumvent detection (so called adversarial attacks), making the detection of deepfake videos with machine learning a Sisyphean burden.

But there is an even larger problem with post-hoc filtering of deepfake media; a problem related to human nature and our tendency to become reliant on technologies to think for us. Think of automated spam detection and anti-virus software. In recent years, we have come to rely on these tools to determine for us which of our hundreds of emails and files we receive every day are dangerous and which are harmless; when our anti-virus does not complain about some file and our spam filter does not filter out a message, they must be legitimate, right? Well, computers around the world get infected with viruses and ransomware every day. The moral of the story; algorithms make mistakes, but we still rely on them. And just like anti-virus software and spam filters, deepfake filters will make mistakes, however infrequent they may be.

And this is where the danger lies. When we come to rely on imperfect filtering technologies to discern real from fake, what will happen when a mistake is made and a fake remains undetected? If we can learn anything from their matured counterparts, any mistake by the algorithm would render a deepfake to be believed and will likely be seen as legitimate (at least initially). Conversely, real videos wrongly detected as fake would likely be distrusted. Our sense of truth would become as good as our detectors are at recognizing fake media.

Detection of deepfakes will not be sufficient to prevent the aforementioned consequences of fake media from coming to fruition. In the worst case, it may even strengthen one’s belief that some video is real when falsely allowed to pass through. To prevent malicious deepfakes from reaching their audience, the problem will need to be dealt with at the source.

Treat the source, not the symptoms

As deepfake technology advances and the manipulation of video becomes effortless, what can be done to mitigate the impacts it may have? So far, the proposed solutions only try to put out the fire after the fact, whereas we should try to prevent the fire in the first place. A solution could be found in Blockchain technology. In short, Blockchain is a secure, digital ledger which stores information in a way that ensures it cannot be easily tempered with. With Blockchain-enabled devices that transfer videos the moment they are recorded, social media could use that Blockchain to verify posted content and ensure that media edited after the fact cannot be published on the platform, preventing manipulated content from seeing the light of day. Thus far it has only been tested with the Department of Homeland Security, and it may pose a bit of a challenge for social platforms. People would need upgraded devices to allow images and videos to be digitally signed, and, as people often wish to apply filters to their pictures after the fact, some form of mechanism will need to be in place for harmless editing to remain possible. One of the staples of social media has been meme culture 一 take for example Senator Bernie Sanders at the recent inauguration who was edited to appear in tons of other situations. Such a solution as Blockchain would be a deterrent for people to create deepfake content, but could deter the general user base of social platforms from posting as well.

However, apart from technological solutions, legislation may also prove effective. While tech companies are looking for solutions in the form of detection, governments have been trying to push for more regulation through legislation. In the United States, the DEEPFAKES Accountability Act was introduced in 2019, which requires all deepfakes to bear a disclaimer and establishes a right for victims to sue the creators. The state of California has also proposed a bill making the creation and distribution of deepfakes of politicians within 60 days of an election illegal and allows people to sue if their image is used in sexually explicit content. The Cyberspace Administration of China announced new rules concerning media online with a ban on the publication and distribution of deepfakes without proper disclosure, almost going as far as banning the technology outright. Even though these laws might be hard to enforce, as people who create fake media for malicious reasons will not adhere to these laws and publish their creations anonymously, it does set a legal foundation for something that previously was not fully covered under the law and can serve as a further deterrent for creating malicious deepfakes.

Deepfake technologies may in the very near future influence many facets of society. We as the scientific community should therefore reconsider the roles we play in the development of these algorithms as well. Many of the technologies used to create deepfakes have their roots in academia or are derivatives of scientific research. For one, there should be more oversight on how research is performed and most importantly where datasets and models are published and how they are distributed. When deepfake algorithms are not published alongside research papers or made open-source, the access that everyday people will have to creating high-quality fakes will be greatly reduced, thus limiting the ways regular people can freely use such technologies for their own agendas and distribute manipulated media online. One might say that it is too late for this; however, as of today, deepfake technology that is easily accessible for the majority of people is still in its infancy and can often be easily discerned from reality with the naked eye. Nonetheless, it will be important for researchers to consider the possible negative aspects of publishing and open-sourcing their research. With the ever-increasing presence of AI in our society, it is of essence to think about research not just scientifically, but also ethically and what the technology would entail for society.

Only time will tell

Despite not having as big of an impact on society as initially thought, AI-powered deepfake technologies may soon become ubiquitous with unprecedented implications for society and the political sphere as a result. We have mentioned the effects of deepfake and facial reenactment technologies on society from the spread of political misinformation and non-consensual pornography to the plausible deniability of audiovisual evidence. We then argued why the current measures of defense will not hold up to the advances made in the technology in the coming years and why legislators, platforms and the scientific community must instead consider tackling the spread of deepfakes at a more fundamental level; that is, the development and distribution of these technologies themselves.

Whether any of the grand fears of deepfake technology will materialize will remain a matter of speculation. But, until that time arises, it will be wise to reflect upon the potential dangers these technologies may pose for society in the near future and strive towards preventive measures that ensure these fears will not materialize.