Researchers’ earliest efforts to put Artificial Intelligence (AI) into the law field dates back to the 1970s, with a software called ‘TAXMAN’ developed for cases related to tax law. TAXMAN was essentially a rule-based auto decision-making system, which is capable of performing legal reasoning based on the ‘facts’ it was given and a few predefined legal ‘concepts’. Compared to today’s AI systems, TAXMAN is so primitive that it looked like something from the stone age. The author of TAXMAN, L. Thorne McCarty, wrote an article in 1976 reflecting on this system, in which he pessimistically concludes:

that nothing as complex as legal reasoning can ever be represented in a computer program

Reflections on TAXMAN: An Experiment in Artificial Intelligence and Legal Reasoning

Most researchers during that time somewhat underestimated the future of AI in law. Recent advances in AI technologies such as large language models (LLM) open up exciting new horizons where AI can perform better in a wider range of tasks. However, the debate has never stopped on whether we should use AI in law at all. Opposers view AI in law as the death knell of democracy, and we would be controlled by some robotic overlord or an evil corporation. Their worries don’t come from nowhere, however let’s talk about the significant benefits of using AI in law first.

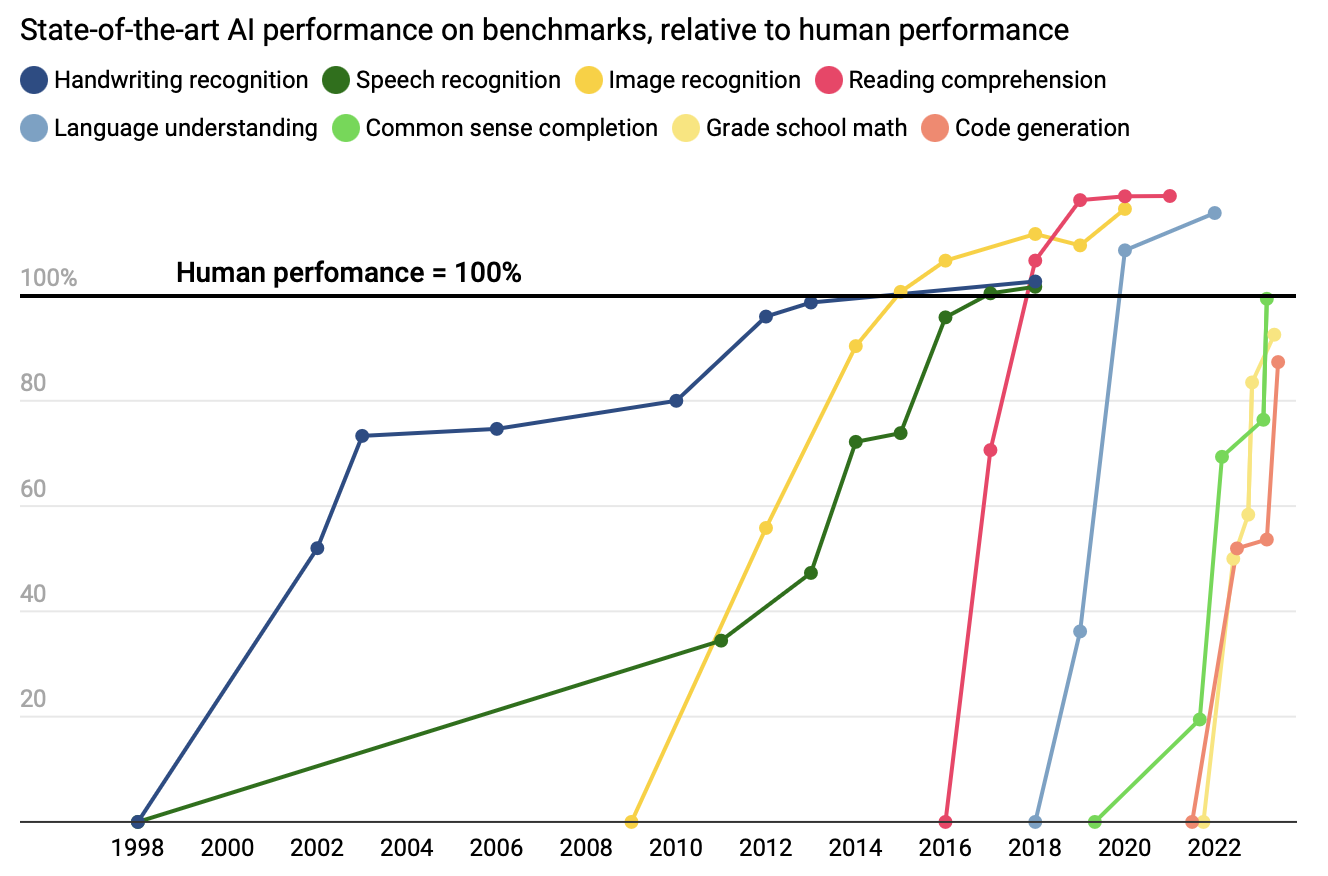

AI is much more efficient. In traditional legal practices, the review of legal documents relating to a case can be an overwhelming challenge for a practitioner because there could be so many of them, for example in a large case the case file could contain multiple thousands of pages. AI is a perfect solution to that. With the ability to sift through the vast volume of legal data, AI accelerates the information retrieval process so that human can focus their attention on more nuanced or complex aspects. Not only can AI do it faster than us, but it can also do it better. A research in 2023 shows that in the tasks of reading comprehension and language understanding, AI has already outperforms humans with a large margin. Some of the largest law firms have already begun developing such AI systems. Linklaters, a law firm based in the United Kingdom, introduced an AI chatbot in March 2023 built on Microsoft Azure AI, which is capable of answering users’ legal queries based on knowledge from a huge amount of Linklaters documents.

AI is more objective. This is bound to be a controversial statement because one of the most common opposing voices for AI nowadays is that it could contain bias or prejudice from its training data. Let’s start with a cliché joke first:

Two men are walking in the woods when they see a bear.

One man bends down to tighten the laces on his shoes.

The other man looks at him and says, ‘Are you crazy? You can’t outrun a bear!’The first guy replies, ‘I don’t need to outrun the bear. I just need to outrun you!’

This joke is a broader reflection of how we tackle some challenges. As long as the current solution can ‘outrun’ the available alternatives, we should consider it to be beneficial and try to adopt it. In terms of bias, the question is not whether AI is or ever can be unbiased, but should be whether it can do better than its human counterparts. Or, if we accept the fact that both AI and humans are biased, is the bias inside AI more correctable than that of the humans? Yes, it is.

Bias is something that is so deeply rooted into human psyche that it can never be fully eliminated. The existence of bias is everywhere, and it can never be simply attributed to reasons such as ‘misunderstanding’. There has already been numerous research in psychology field proving that people who are smarter or with more professional expertise are actually sometimes more prone to bias, and it could be more difficult for them to identify their own bias. Look into the real world, we can also witness tragic events caused by bias throughout history, even till now. Human bias is something that is unrelated to how high the average IQ is or how civilized the society has become, it is bound with human nature.

On the other hand, the AI operates at a completely different logic. Mathematically speaking, the bias inside an AI system is an exact reflection of the bias inside its training data. For example, if the historical data used to train the AI model contains prejudice against a specific group of people, then the model would be prejudiced against this group, too. This is somewhat like conducting a survey. If the people participated into the survey is not a good representation of the target group, then the result from this survey could be biased and unsuitable to assist in decision making. However, this behavior also limits the range of where bias could exist, which means just like survey conductors trying to cover a more evenly distributed participants, AI developers could take technical measures to mitigate the effect of bias in data. Some pre-determined features such as race or gender could be stripped from the dataset to prevent AI making biased decisions based on these factors, and the increasing amount of datasets would make using more diversified data feasible. It might not be possible to completely eliminate the bias existing in AI, but we could easily make it outperforms humans in terms of objectivity.

From what we’ve covered now, applying AI in law is both efficient and more objective, and it just looks so promising. However, there do exist some arguments that make sense if we consider some recent events. There was the case of this lawyer, Steven A. Schwartz, who asked ChatGPT for similar cases and the chatbot gave him bunch of fake case citations which doesn’t exist at all. This case highlights the ‘black box’ problem of AI. For most AI models used nowadays, the process from user input to AI output is just a huge bunch of mathematical operations such as matrix multiplication or convolution, which is totally uninterpretable for humans. This issue is more obvious for the recently emerged generative AI systems such as ChatGPT. For a user query, generative AI by design returns the reply with the highest probability given the context (it’s not a very precise description, but would do for now), and there is no way to guarantee that whether AI gave a valid result based on user requests, or just made up an answer. This means that there needs to be manual review if we would like to use AI in critical scenarios such as legal decision making.

That poor lawyer might not receive the 5000$ fine if he understood the possibility of AI making up answers, or if the law firm and government had rules on using AI-generated materials in court. This leads to the topic of regulation and education, which is how we are going to take AI in law seriously. Regulations should be in place to reduce the possibility of AI being abused, as well as defining guidelines to make sure legal AI is developed with maximum objectiveness in mind. Education to the general public would also be necessary to inform people the benefits and risks of AI, encouraging the demystification and responsible use of AI. The era of AI in law has come, and it would be up to everyone to make legal AI beneficial to everyone, rather than creating a cyber dystopia.