Dubai, December 2023. During the UN’s climate summit (COP28), representatives of 198 countries agreed to transition away from fossil fuels – a world first. Moving from one of the largest petrostates to its second-largest consumer, the USA, we see the importance of this topic being underlined beyond the diplomatic world. In a video that’s somewhere in between a marketing stunt and corporate responsibility, Apple welcomes “Mother Nature” as a shareholder to the board meeting. Their climate pledge can be added to an already quite long list – 900 out of the largest 2,000 corporations have such pledges. The consensus on the need for solutions to combat climate change, is in stark contrast with the debate on the million-dollar question: how are we gonna do it?

Enter the world of Artificial Intelligence (AI). We believe AI holds the promise to not only enhance our daily lives but also to offer revolutionary solutions to global challenges. One notable instance illustrating this potential is AlphaFold 2, an AI program that allows for the prediction of protein structures. These structures are crucial in understanding the biological functions of proteins, and due to the significant time reduction compared to prior tools, AlphaFold 2 is a major breakthrough in the so-called protein folding problem, which is widely studied in the field of bioinformatics and molecular biology. This has led to numerous important insights in the protein structure domain and initiatives reducing our ecological footprint, as researchers are already using AlphaFold 2 to engineer enzymes that can recycle polluting plastics.

Additionally, AI has far more to offer than protein and enzyme engineering, it is undeniable that AI will have an impactful role in addressing the climate crisis in many other ways. A 2022 BCG report on this matter, identified how AI can aid us in three ways: mitigation, adaptation and resilience, and fundamentals. In this article, we’ll dive into the former two subjects. While mitigation, consisting of measuring, reducing or removing emissions, is most discussed in the public debate, we also look at adaptation and resilience, as 3.6 billion people live in areas highly susceptible to the effects of climate change. We believe that AI holds the power to enable both citizens and global leaders to take their part in the fight against climate change, and will explain why in this article. We’ll also discuss concerns, ranging from the energy use of AI to privacy.

Restoring the Energy Balance

Every day between noon and 5 pm, when solar power reaches its maximum, the power grid is confronted with a surge in electricity inflow. Meanwhile, homeowners are not making use of this energy at peak times. This imbalance, also referred to as the “Duck Curve” by the US Dept. of Energy, is causing great amounts of stress on the grid (leading to power outages in extreme cases) while fossil energy sources are still needed at off-peak times (still accounting for 54% of electricity production in The Netherlands).

With the massive growth in green energy sources, the need grows for a smarter way of handling their volatility. The fundamental idea presented here is the idea of a smart grid, where data is transported alongside energy. This idea is not new. In fact, the first Dutch homes were offered a smart meter in 2012, and nowadays most Dutch residences have one. Another development is the massive rise in IoT-capable devices (also known as “smart” devices, a smart fridge or smart thermostat, for instance). Almost 75% of Dutch residencies own an IoT-capable device. While most features of IoT devices can be considered quirky at the moment, a clear use case emerges when we make these devices truly interconnected.

We envision a future with a new smart grid, one behind the front door. A central, AI-powered controller gathers data on all smart devices in one’s house, and all available energy sources (weather forecast for solar panels, hourly grid energy prices, (car) battery charge level, and so on). The system monitors, models and orchestrates the energy balance of the house, by directing energy when there is an abundance of it. The beauty lies within the simplicity for the end user, only seeing an extra option when powering their dishwasher: “done within the next 12 hours”, or noticing the house getting pre-heated for the night because the sun is still shining. This future has already been envisioned by researchers and companies like Bosch have designed early adaptations of such a system, which has the capability of enabling end-users to use cheap, green energy, thus contributing to the mitigation of climate change. The U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission estimates that demand-side management systems like these can reduce peak load in the US by up to 150 gigawatts.

These innovations cost money, rendering them unavailable for some. Energy poverty is already a serious problem by itself, so governments should subsidize these kinds of measures. Whether it be for the climate, or as a less costly alternative to revising the entire power grid. Another concern is regarding data. About ten per cent of Dutch homeowners rejected a smart energy meter, worrying about their privacy. We believe the solution can be found in a decentralized architecture, where the AI controller installed at home trains the model locally, without sending any data to the outside world.

Improving resilience for vulnerable communities

Various countries in Europe have experienced severe weather conditions as a result of climate change in recent years. Flood waves in Slovenia, heat waves in Italy, and forest fires in Greece are just a few examples. Specifically, here in the Netherlands, the NOS reports that the summer of 2023 will be among the top 10 hottest summers ever recorded.

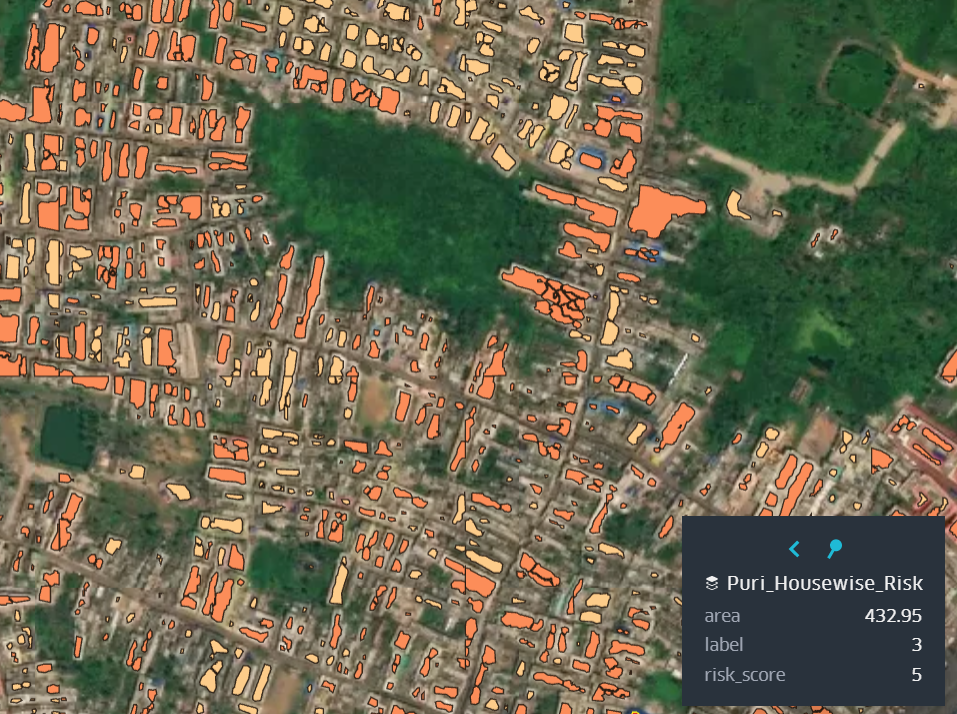

However, various vulnerable communities face conditions of even greater severity, for example, India and the Philippines, which have encountered many cyclones in the past decades. The Philippines on its own faces 20 cyclones each year on average, and super typhoons like Odette have resulted in hundreds of deaths and millions of people affected. One initiative aimed to combat the effects of these extreme weather events is SEED, which stands for Sustainable Environment and Ecological Development Society. This organisation actively mitigates among others the effects of cyclones, using an AI model called Sunny Lives developed collaboratively with Microsoft. Prior to the cyclone, Sunny Lives can identify the most vulnerable houses by analysing the estimated affected area and categorizing houses into low to high risk by looking at properties such as the type of roof. This is groundbreaking, as this allows for fast and efficient evaluation and proper notification of vulnerable households, for example, household-specific instructions to prepare for the approaching cyclone.

Another climate event that has long-lasting ramifications is sea-level rise, a result of the melting icebergs. The Antarctic ice sheet has been significantly decreasing since 2016, and with the increasing global temperature accelerating this effect, the icebergs will come to an irreversible point at the end of this century if we continue at this pace. Observing icebergs has been a challenge, as factors such as weather, daylight and complex environments interfere with the observation methods. Using AI, this observation can be conducted 10.000 times faster than humans, providing the locations of icebergs, as well as insights on the amounts of melting ice.

The Hungry Elephant in the Room

While the solutions presented above have a big potential, we must also discuss a reason to avoid AI: its energy consumption. In 2019, researchers calculated that training a medium-sized AI model emits 626 thousand tons of CO2 equivalent. For climate-oriented AI models, this could create a paradox where the bad effects on the climate outweigh the good ones. We believe, however, that this will not happen if AI is implemented responsibly. The AI controller in the first solution would be shipped out with an ultra-low-power AI processor, and it would gather its energy for modelling only when there is an abundance of it. It is a simple example of the leveraging effect AI solutions can have: while they consume energy, they can help us save a lot more. Besides that, researchers and policymakers are already working on guidelines for sustainable AI.

Conclusion

We discussed two ways in which AI tools can help us fight the climate crisis. A DMS system would enable citizens to use more green energy, more efficiently. It is an example of how AI can be used to democratize the energy market while increasing sustainability. Subsequently, we looked into models that can aid communities in becoming more resilient to the consequences of climate change, and how researchers use AI to map its effects a lot more efficiently. While we acknowledge that AI tools use quite some energy, developments like ultra-low processors and guidelines on sustainable AI will address this consumption for a big part. The energy that will still be consumed by AI should be sourced from non-fossil fuels, but will buy us one thing that we need desperately in the climate crisis, but no one can buy: time. We conclude that the environmental cost of AI development is wellworth the potential it poses.