“How are you feeling right now?” the therapist asks; on the patient’s answer that they’re panicking he replies “Oh no, I’m Sorry! Breath along with me for a minute and then we’ll talk more about it OK?”. The described conversation is not one happening in psychotherapeutic practice, and the therapist is not a real person. The patient is holding this conversation with Woebot, a Chatbot powered by artificial intelligence (AI) that assists people with mental health issues via chatting, as demonstrated in an advertisement video. It exchanges millions of messages with users with mental issues per week by checking in on them daily and providing a platform for them to spill their thoughts and feelings. A user describes Woebot as “therapy that you can take anywhere with you” – Could Woebot pose a viable alternative to traditional therapy? The need to augment existing therapeutic structures is great: Up to 56% of all European adults with a major depression receive no treatment. The main reasons for insufficient treatment are limited access to specialist institutions, long waiting times, failure to detect own need for help, financial hurdles, as well as stigma about mental disorders. At the same time, mental health prevalence is still rapidly increasing and is currently at an all-time high: As of 2020, roughly 26% of the European population was affected by mental disorders of varying degrees, causing 30 – 40% of sick leave at work in western countries. Not only are many people already affected by mental disorders, but the trend is also increasing drastically: In the decade from 2007 to 2017 alone, the WHO registered a 13% rise in mental health conditions. The strain of a recent pandemic, political uncertainties, and war will take an additional toll on society’s mental health in the coming years and decades. The situation is concerning. A change in mental health care is urgently needed in order to cope with the ever-rising treatment demands. While AI is often associated with a negative mental health impact by causing job uncertainty or excessive social media use, advances in conversational AI in particular are likely to play a key role in addressing the deficiencies of mental health care systems.

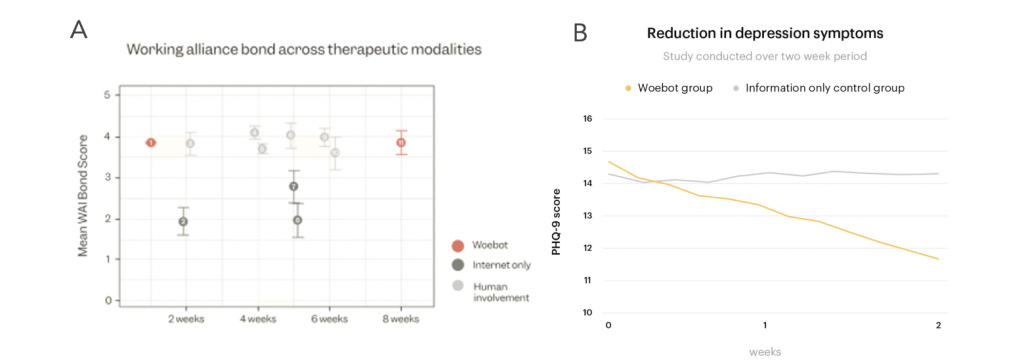

Woebot is by far not the only AI-powered therapeutic assistant around, others include Wysa, Pyx Health, X2ai, or clare&me; the reason for the boom is the promising outlook that these systems provide for mental health care. They are immediately accessible to everyone with a smartphone, come at a much lower cost compared to traditional therapy, and are available anytime & anywhere. Especially for those who might be repelled by the temporal, spatial and financial hurdles of traditional in-person therapy, artificial therapy agents could provide a viable solution when in need of support. A common objection towards machine-based therapy is the lack of empathy and genuine human interaction, as this could be achieved by a computer program. In a meta-review, scientists indeed found that the empathy and genuineness exhibited by a therapist were at least moderately predictive of the therapy outcome, as well as the therapist-patient alliance formed during the sessions. Even though the claim that AI lacks the ability to engage in genuine empathic interaction is (still) correct, research found that patients were able to form bonds with Woebot that were comparable to that of human-human bonds in strength (see Figure A below). Investigations on the effectiveness of X2ai’s chatbot “Tess” additionally report a positive effect of engagement with the artificial agent and decreasing symptoms of depression (see Figure B below). Thus, despite a lack of an actual human counterpart, artificial therapists seem to be effective nonetheless.

Figure B: Reduction in depression symptoms over time of “Tess” use. Source: Fulmer et al., 2018

These encouraging results are based on the current, still deficient state of technology; given the rapid developments in the field of conversational AI, however, artificial agents could even be able to act as autonomous therapists in the near future. AI technology may combine human-like communication with possible emotional understanding, allowing therapy agents to understand clients’ stories, interpret the emotional context, and respond in an appropriate empathetic manner guiding the patient on their journey for better mental health. With such an advance, the bond between sensitive artificial agents and humans could get even closer to that of a human alliance, and their effectiveness could be considerably improved. What concern remains, however, is the matter of acceptance: The mere knowledge of interacting with an artificial entity and not another human is detrimental to using and endorsing an artificial therapy agent, regardless of how helpful the content might be perceived. This is nicely demonstrated by a recent experiment by Koko, a mental health platform providing support to people in need without using AI: In the experiment, the human responses provided to the users’ requests were replaced by responses generated with GPT-3, an advanced conversational AI. Even though the AI-generated messages were rated as more helpful compared to the human-generated answers, the rating decreased drastically when the user learned the content was created by means of AI. A possible reason for this lack of acceptance might be the prejudice about interacting on an emotional level with an artificial agent. This, however, might be overcome as interaction with AI is becoming normal with ongoing technological progress. Interestingly, exactly the criticized “inhuman” nature of artificial therapists appears to be even beneficial for others: A recent study reported that some patients actually prefer artificial conversational partners, due to the decreased perceived stigma of talking about mental issues. This is a particularly important point, as the stigma associated with mental health problems is a major reason for not seeking treatment when it is needed.

Due to its easy financial, temporal and spatial accessibility as well as the “anonymity” with which the service can be explored, therapeutic AI applications in sum significantly lower the entry barrier into therapeutic structures. In support of this claim, a Woebot user states: “I never would have gone to a psychologist, Woebot kind of pushed me towards it”. Despite those promising-sounding results, none of the aforementioned applications aims to replace human therapists as of now, as exemplified on Woebot’s Homepage. Instead, artificial therapy agents as an augmentation of currently existing human-based therapy structures. For example, artificial therapy agents could help to prevent a delayed treatment of mental disorders, by indicating that a user should seek professional treatment if signs of a disorder are detected. This is highly relevant, as delayed treatment is strongly associated with a decreased therapy outcome. In a different scenario, therapy agents could serve as a helping instance when the human therapist is not available, e.g., between sessions or while waiting for a therapy place.

However, in the scenario where mental health support is at the user’s fingertips at all times and everywhere, concerns arise about people’s dependency on technology and their ability to cope with arising problems themselves. The fear is that the opportunity for instant help leaves people with a decreased resilience, missing adaptation to outer circumstances, leading to a higher vulnerability. Similarly, people having an instance by their side that is always available to listen to their sorrows and problems could leave people more prone to seek support from machines and not from human allies, possibly isolating people from their friends or family. This might not be a serious concern as of now due to the limited capability of current therapeutic AI agents; in future scenarios, however, when AI agents get more advanced, this might be a problem to consider in the design of such technology. The potential abuse of therapeutic assistants could (and should) be prevented by introducing usage limits or designing the therapist to highlight excessive app use. Not only could this help to prevent deteriorating patient resilience and loss of human contacts, but it could also help to achieve the therapeutic goal of the AI agent. The focus of a therapist – whether a human or an artificial agent – is not to provide immediate solutions to a patient’s negative emotions, but rather to provide guidance for a patient to solve it for themselves in their everyday life. A good (artificial) therapist thus not only gives advice on how to cope with problems but also regulates how much a patient can rely on their help when necessary. Just like human therapists, artificial therapists could recognize when help would be disadvantageous and act accordingly.

Conversational AI has a large potential to provide a remedy for the current deficiencies of an overburdened health care system. The current state of technology and the ongoing developments forecast a future with AI agents supporting and augmenting existing therapeutical structures. A lower barrier to mental health treatment through a decreased financial burden, better accessibility, and decreased stigma could help more people receive the help they need, as well as improve the care for people already in treatment. AI can further influence mental health care beyond what is outlined in this article, for example by helping to understand the underlying causes of psychological problems or the detection of mental disorders. In all possible applications of AI in the context of mental disorders, special ethical and legal matters of capturing and handling sensitive patient information have to be considered. We emphasize that these technologies have to be developed and applied with the same care as traditional human-based therapy, however, we are convinced that conversational AI is of great benefit to the deficient mental health care system.