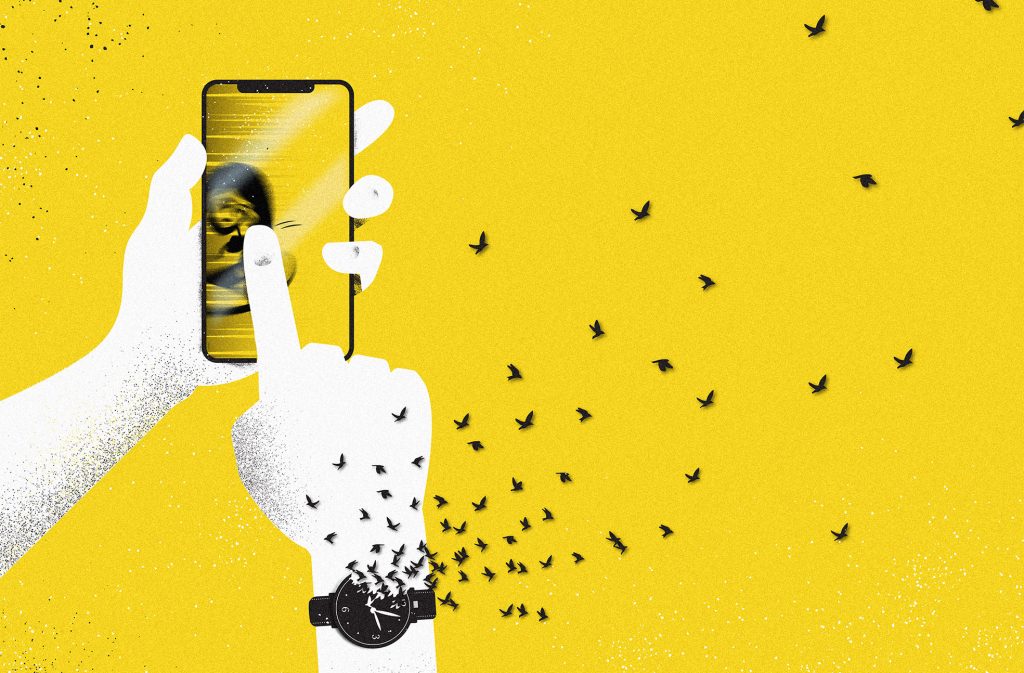

The digital age has created an attention economy, where those who can hold our gaze the longest make the most money. But at what cost? In this op-ed, we explore the dangers of an endless stream of fast-paced content served by AI-powered recommendation algorithms. How it’s changing the way we live our lives. Not only by how we consume content, but in how we create it as well. We plead for a more mindful approach to our digital lives: living with intent. Arguing against mindless consumption of fast created content led by what our devices recommend.

Being mindful of the degree of intent in which we choose our daily occupations leads to a more productive use of time and efforts. Even in leisure. Time spent relaxing after intentionally deciding to go read a book, take a walk, or watch a specific movie for an hour or two, is much more enjoyed than the time that flies by when we are scrolling away, which often happens for a non-predetermined amount of time or with a non-predetermined goal.

Attention economy

The inception of the internet has introduced a genuine information revolution: any topic, no matter how niche the subject matter, has become readily available. This gave us the un-throttled ability to consume everything we deemed interesting at an instant, with few apparent risks at first.

However, as we we will discuss, what we deem interesting is easily manipulated. With an abundance of interesting content, our attention becomes a limiting factor of consumption. Approaching attention as a limited commodity, attention economics applies economic theory to solve various information management problems. Attention should be viewed as a scarce resource in an attention economy. As dr. Crawford puts it in his book The World Beyond Your Head: On Becoming An Individual In An Age Of Distraction: “Attention is a resource—a person has only so much of it”. If attention is a commodity, that implies it can also be exploited for profit. One could argue that social media companies certainly subscribe to the idea of an attention economy. Those who can hold our attention can serve us ads, thus making money. Most web companies are therefor incentivised to keep us hooked in an effort to serve more ads and make more profit.

Attention is a resource—a person has only so much of it

Matthew crawford

Those who can capture our interest the best, can hold our attention the longest. The internet has become an intricate collection of slot machines. Due to forces present in our collective ancient past, humans are wired to seek out novelty. Developers know this and because attention equals cash, website design is thus focused around tapping into our addictive tendencies to seek novelty. The actions that reward us with novel interesting content get rewarded. Two factors influence the strength of this connection: Simplicity of action, and time between action and reward. The clearer a certain action leading to a reward is, and the sooner after the action the reward follows, the stronger the dopaminergic response to that actions becomes. Therefore, an action like swiping up on your phone screen to see a new TikTok video is the perfect recipe for a powerful psychobiological connection. Every swipe provides a large dopamine hit, and in a neurological process similarly to developing drug or gambling addictions, one quickly starts building a bad habit they lose control over.

Consumption and creation

This is where Artificial Intelligence comes into play. AI has a dual role in the attention economy, aiding in the consumption and creation of online content.

On consumption, clever recommendation algorithms are trained to increase screen-time. More screen-time inevitably leads to more ads served, leading to higher profits for a tech company. Trained through reinforcement learning, these algorithms are very effective at serving content which interests the user. The training objective? Maximise retention.

Two notable examples of successful recommender algorithms are YouTube’s Auto-Play feature and TikTok’s For You page. Both systems have an incredibly strong pull on your attention. Through the recommendations people discover interests they never knew they had, diving from rabbit hole to rabbit hole in hours long binge sessions. Teens now spend an average of 91 minutes a day on TikTok. Even the first cases of true YouTube addiction have been reported.

The nature of how these recommendation algorithms are trained does not necessarily lead to the content served being related to what a user was watching, nor does it have to be of a journalistic standard or even truthful. It just needs to spark your interest, keep you engaged. The dangers of these recommendation strategies leading to misinformation and echo chambers protected by filter bubbles have been widely explored. However, the art of attention retention through an infinitely scrolling video stream tailored just for you poses even more dangers.

The act of enchantedly staring at a screen, scrolling through an endless stream of thoroughly useless information is dangerous in and of itself. We are wired to seek out new information, but what if this quest is no longer intentional? While one might discover interests they never knew they had, we also tend to forget these interests just as fast. Never really acting upon them in any useful way. One week you might be infatuated with primitive technology, the next you’re into citizen police audits.

Fast content consumption unquestionably introduces a need for fast content creation. AI assists in the creation of fast content tailored for recommender algorithms to serve. Computer speech (TTS) is already being used to create content faster. Supporting images are generated with the click of a button. With the rise of generative AI, content creation has become a low effort endeavour. An entire children’s book can be written, illustrated, published and printed in just one weekend. In an attention economy where quantity supersedes quality such accomplishments are even praised.

Note that the bar for online content is not very high. As mentioned above, successful content only needs to retain someone’s attention, not inspire or even truly entertain them. With the current state of generative AI systems it is not hard to imagine a computer being able to generate simple entertainment videos in the near future. In fact a proof of concept can already be found in Nothing, Forever, a show about nothing, that happens forever. This Seinfeld inspired live TV show is generated by an AI model and is permanently streamed on Twitch.

Currently social media platforms rely on creators to generate content. In return a creator earns a significant share in the advertising profits. When will AI cut out this middle man?

Imagine a world where we mindlessly scroll through an endless stream of personalised content. Generated live, just for you at each flick of your finger.

Fast content, fast life

The rise and use of these technologies for both consumption and creation of content is indicative of the same underlying problem: life is getting faster. We don’t take the time for things anymore. We value quantity over quality. Speed over depth. We do not intend to experience our experiences fully and in the moment, instead we indulge to have as many experiences as possible.

It’s fine to intentionally decide to actively dive into a rabbit hole from time to time, just like planning to read a book or to go for a run. However, in our experience, social media usage is seldom intentional. It’s not an uncommon occurrence to decide that you don’t have the time to spend on some leisure activity, and subsequently spend way more than that amount of time scrolling away. The temptation of applications based on recommender algorithms can cause you to bypass the intentional plan-making used in deciding how to spend your time, and hijack your scarce attention.

The result is a phenomenon seen in many young people; they have no real hobbies anymore. They lose focus, hopping from one rabbit hole to the other. Dan Scotti, lifestyle writer at the website Elite Daily, wrote: “With a pair of iPhone speakers and a Netflix subscription, I rarely feel as though I’m missing out on anything”. One could say that there is not really a problem with high media consumption as a pastime activity, but there is a good case to be made for having proper hobbies. As Dennis Prager from National Review puts it: “There is a world of difference between being active and being passive, between creating something and watching something, between doing something and being entertained.”

Another often heard argument is that it’s just entertainment. What harm can be done by engaging in a bit of fast entertainment like YouTube, TikTok, or Instagram? However, a similar argument could be made for entertainment industries of which the dangers are more well known and established with the public. What is the harm in gambling? How bad can drinking on a night out be? To most these indulgences remain harmless. To some however, and in the case of fast online content an ever growing group of youth, they pose a serious danger of addiction.

In a world without addictive engineered recommender systems, entertainment would still be enjoyed by consumers. The choice of seeking this pleasure would simply have to be more intentional. Causing users to seek out quality content they want to watch. This would increase overall quality standerds as compared to the current situation and make people get distracted less.

“There is a world of difference between being active and being passive, between creating something and watching something, between doing something and being entertained.”

DENNIS PRAGER, NATIONAL REVIEW

Intentional living

We do not have a direct solution to offer in this essay. The technology is here to stay. Generative AI-models offer wonderful tools for creation, however it is likely that in the attention economy of today they would be used to create low quality fast content. We do not argue for more regulations on recommender systems either. Nor should governments impose time limits on entertainment apps. We find that these solutions are undesirable and perhaps infeasible in the liberal society of today. The problem presents itself on an individual level, and the solution should be tailored towards individuals too. We argue for awareness. Consumers should be aware that their attention is a commodity. By embracing the attention economy as a reality, consumers should spend their attention with intent. Treating it just as valuable to themselves as it is to the platforms that profit from it. With this awareness it is unlikely that content is sought out because of anything else other than quality. Therefore, producers of content would be incentivised mainly to create quality products.

True quality requires effort. Fast content should not be rewarded with your attention. Our advice is to live an intentional life. Be aware of the risks of addictive and/or low-quality entertainment and be intentional about the way you spend your time. Do this, and you should be able to navigate this new world full of possibilities at your fingertips just fine.