The cognitive and behavioral capabilities of an artificially intelligent (AI) agent are increasing rapidly. It has already been over half a decade since algorithms started performing better than humans on labeling the content of images online. This might seem a trivial task (it really is not — image labeling is the foundation of computer vision), but algorithms have recently also matched human expert performance on medical matters. One study found that algorithms based on deep neural network machine learning (ML) methods matched the performance of twenty-one board-certified dermatologists in diagnosing skin cancer.

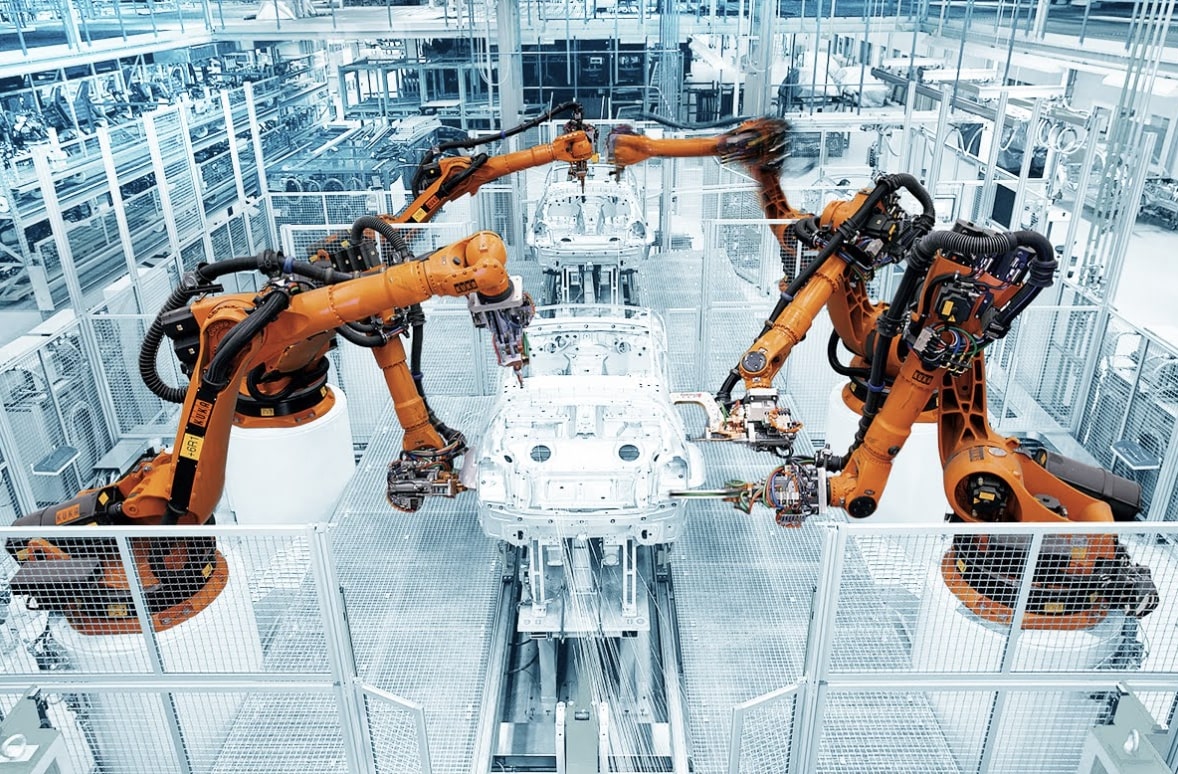

Given the increased competence of algorithms in so many domains of work, the concern of job displacement in the near future has cemented its place in the public conscience. Many people worry that AI will, in a very short time, reach a stage of sophistication in which it easily outperforms humans, in both blue and white-collar environments. According to research done by the McKinsey Global Institute, up to 30 percent of hours worked globally could be automated by 2030, and up to 14% of the workforce may be displaced by the same year.

Some economists also raise concerns about a phenomenon called job polarization — a term that refers to the erosion of middle-skill jobs. With growing numbers of middle-skill jobs being automated, the labor market might become polarized in favor of high and low-skill jobs. In a polarized market, employees might navigate towards high-wage and high-skill jobs (management, research, etc.) — but the concern is that many people who previously occupied middle-skill jobs would now be relegated to low-skill jobs. As a result of such polarization, large discrepancies in salary, education, opportunity, and workers’ rights become serious concerns. Experts predict that the market could be driven towards this bifurcation, as technological advances tend to be biased against the skills that middle-wage workers possess (think routine tasks: calculation, record-keeping, data entry, etc.).

Still, many others believe that AI and automation pose a threat to workers from all levels of skill. Stanford scholar Jerry Kaplan, the author of Humans Need Not Apply: A Guide to Wealth & Work in the Age of Artificial Intelligence, proclaims: “Automation is now blind to the color of your collar.” He posits that we are currently only seeing the tip of the iceberg and that the full repercussions of automation are yet to reveal themselves. With ML applications becoming more prevalent and the emergence of sophisticated methods to navigate through masses of data (a.k.a. Big Data), companies modernize their operations — they begin to question the necessity of an increasing number of jobs, regardless of the collar. A great example is the implementation of e-discovery software that is able to analyze tremendous amounts of legal documents at rates quicker than any human bookkeeper or paralegal. Accordingly, Kaplan predicts that automation may ultimately result in the redundancy of human services across the entire labor market.

With the looming danger of mass job displacement, how should we react to these projections? The key to a proper response is to actually understand the mechanisms by which this displacement will occur. Do the projections mean that come the year 2030, as soon as the clock turns from 11:59 to 12:00, millions of jobs will have suddenly vanished due to being taken over by machines? Not at all. But, we certainly have a tendency to believe so. It is not helpful to yield to one of our deepest human impulses: fear. We should instead seek to recognize the danger and work towards best preparing ourselves for this scenario.

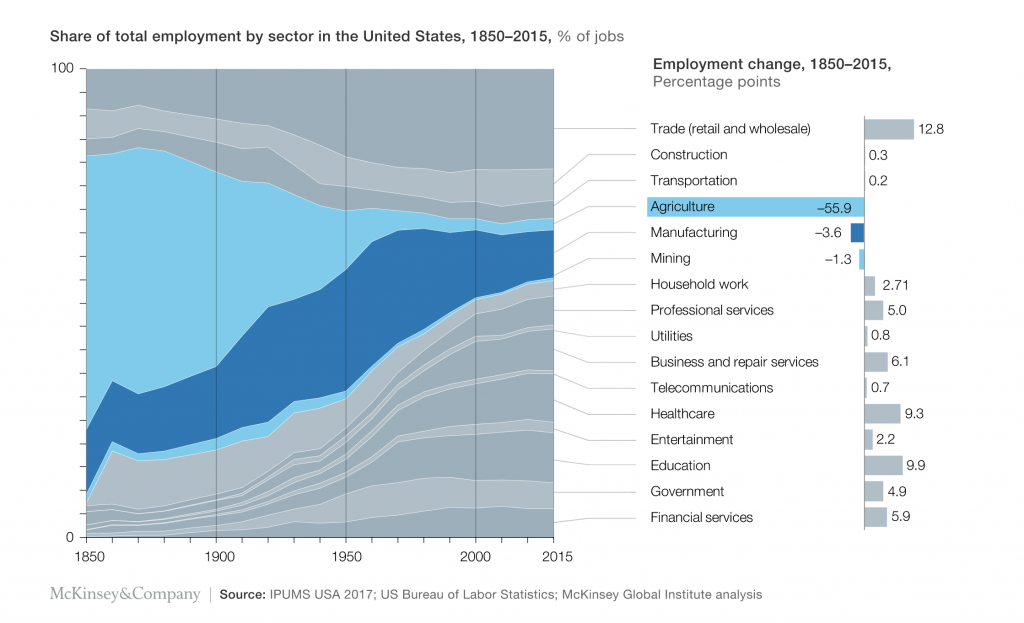

First, we need to understand the mechanism by which new technologies usually penetrate the job market. Perhaps the best example to study this phenomenon would be the industrial revolution and its aftermath. This manufacturing revolution took place in the 19th century, and it changed the world entirely. Levels of efficiency that were previously unknown to humankind were achieved. Machines took over countless manual labor jobs. Sound familiar? Let’s look at the statistics in the aftermath. According to the same report by the McKinsey Global Institute (see below), between 1850-2015, employment in agriculture suffered the largest decline. While the manufacturing and mining industries also took a small cut, many other industries flourished. In just over a century and a half, education, healthcare, and financial services sprang up as sizable sectors for employment. Trade grew significantly, providing many more employment opportunities than before.

What do these statistics mean for the incoming wave of automation induced by AI technologies? We can safely infer, based on the outcomes of the industrial revolution and the unparalleled ability of humans to adapt, that AI will ultimately create as many jobs as it destroys (if not more). These new jobs will either immediately be taken up by workers or workers will quickly adjust to the demands of these jobs. Just like how society successfully acclimated to the wave of automation that came with the industrial revolution, it will necessarily evolve with the post-AI job market.

What does this process of evolution resemble? We should note that even though many jobs will be taken over by machines, other novel jobs will emerge that machines are not capable of performing. These positions will have to do with either the maintenance/proper function of machines and algorithms (such as web development or software engineering) or engaging with the platforms generated by such technologies (think web 3.0 — cryptocurrencies, NFTs, metaverse(s), etc.). Human workers will then adapt to the demands of the new job market and navigate toward these positions. While the examples provided may seem quite limited and obscure for the present time, there really rests a vast land of opportunities before us, and it is scarcely visible just yet. This quote1 from John Markoff, senior science writer for the New York Times, illustrates this point: “If we had gone back 15 years, who would have thought that “search engine optimization” would be a significant job category?”

Another point to consider along with the modernization of skills is the already existing competitive advantage humans have over machines. That is, we possess a set of unique skills, also known as thoughts and emotions, which include but are not limited to empathy, creativity, judgment, and critical thinking. If we consider the fact that algorithms and machines are usually best at predictable activity – since even neural network models must necessarily learn from a given dataset and are not able to improvise beyond the scope of the data provided – one can imagine a job market in which humans are no longer required for such repetitive, formulaic tasks. As a result, an opportunity for a mutually beneficial collaboration emerges. Pamela Rutledge, director of Media Psychology Research center, estimates2 that predictable tasks will be delegated to machines, and humans will focus their time and effort into domains in which they can make a difference.

With this potential division of jobs, these uniquely human traits would be in high demand, allowing us to hone them and distinguish ourselves from machines. Michael Glassman, associate professor at Ohio State University, argues3 that the distinction between the skillsets of AI and humans will be accentuated with the integration of AI into the workplace. He believes this stark distinction will lead us to conclude that AI is not as capable as we think.

Just like how society successfully acclimated to the wave of automation that came with the industrial revolution, it will necessarily evolve with the post-AI job market.

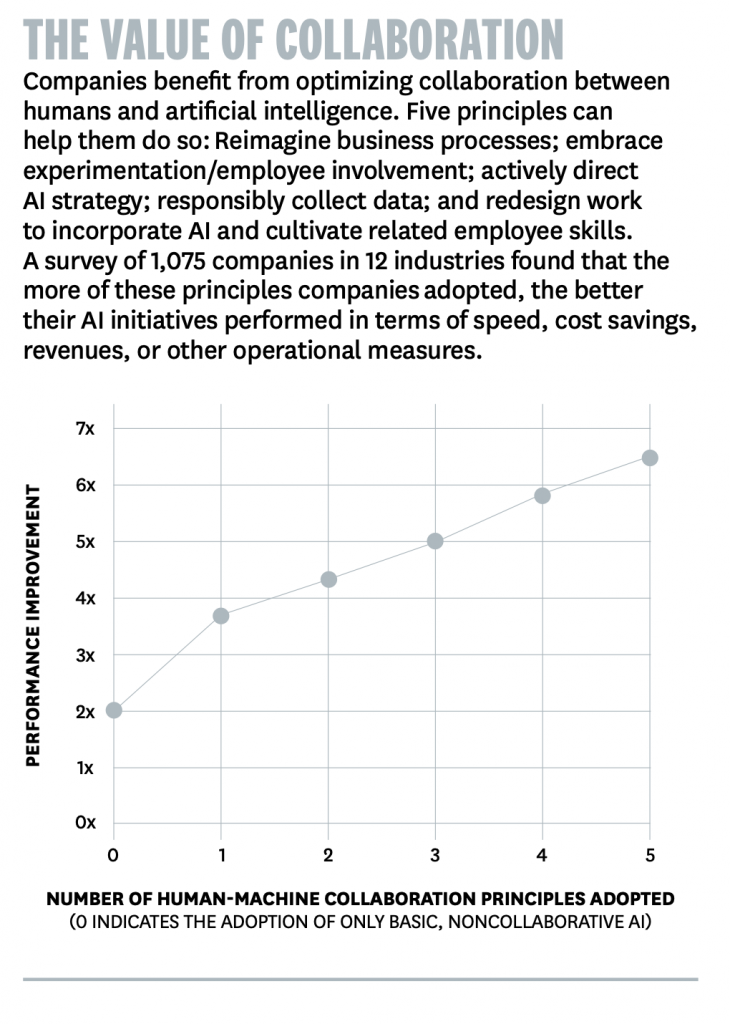

An article published by the Harvard Business Review in 2018 concurs with these arguments. In their research involving over 1500 companies, they report that firms achieve the highest productivity when humans and machines work in tandem. More specifically, the more collaborative principles were implemented in the companies, the higher the performance increase would be (see right). For this new environment in which jobs will involve a “fusion” of human and machine skills, humans must learn new skills to work with machines. They identify three domains in which humans will be chiefly responsible: training (training ML algorithms to function properly), explaining (demystifying the typically opaque processes of algorithms to the general public), and sustaining (ensuring algorithms and machines are committed to ethical standards and function responsibly).

Evidently, there are important steps to be taken to bring about the modernization of the worker’s skill set. But, one may object, this modernization will take time. As new technologies are introduced to the market, many firms will offload employees, freeing up their payroll and purchasing artificially intelligent machines instead. What will these employees do in the meantime? Living paycheck to paycheck, they might not have the means to re-educate themselves on some other skills. If these people do not possess skills translatable to “human” jobs, they will be destined for unemployment with no means to escape.

This objection is valid. With the astronomical job displacement estimations, many workers face this very real danger. In this case, the onus is on our social, legal, and political institutions to interfere. They must acknowledge this danger and plan to provide a safety net, while also offering opportunities for citizens to learn skills that will render them candidates for employment in the new landscape.

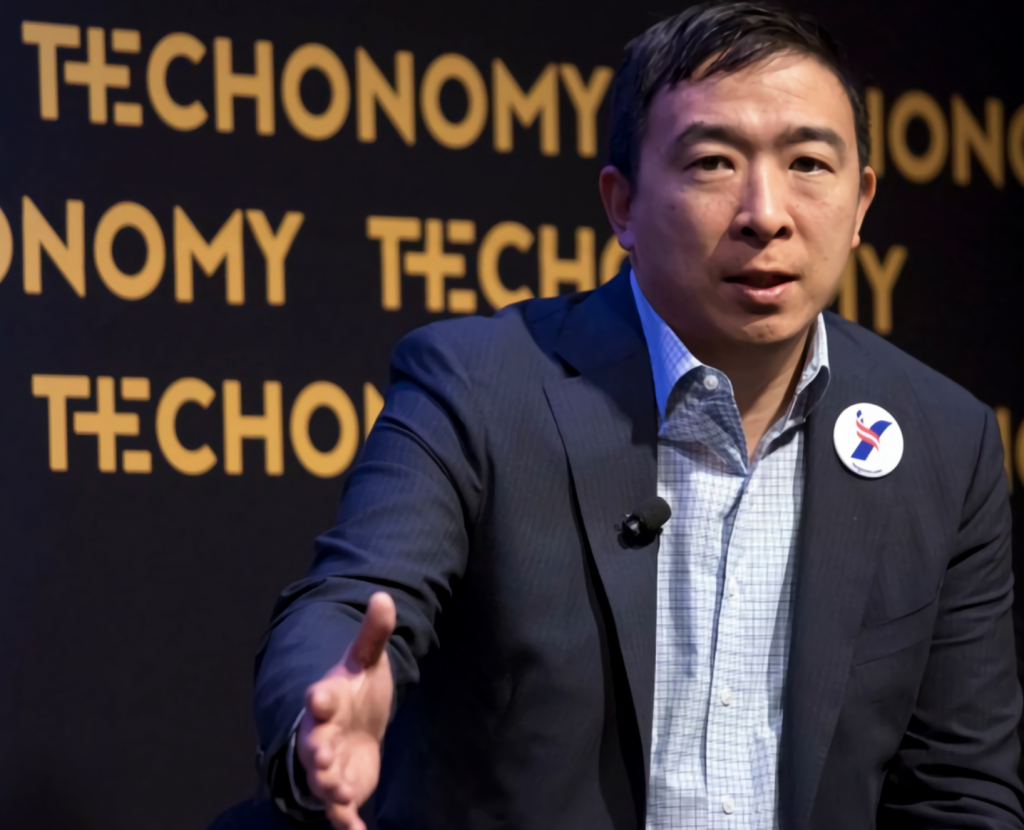

Some politicians have foreseen this threat and proposed solutions. Andrew Yang, a presidential candidate in the 2020 U.S. Presidential Elections and New York-based politician, has outlined his plans to implement “The Freedom Dividend”. This dividend is a universal basic income of $1000 a month — money handed to every American citizen monthly over the age of 18. Yang describes that many Americans have already lost and continue to lose their jobs to automation, and the rate of this job displacement could increase with advances in AI. This dividend is meant to provide relief for citizens who are displaced from their jobs while they navigate to a different job or invest in educating themselves for different skills. Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla and SpaceX and co-founder of Neuralink, has voiced his support of universal basic income.

Andrew Yang ran for president in 2020, and for the mayor of New York City in 2021. He eventually conceded both as it became evident he would lose. Still, the traction he generated, especially during his presidential campaign, prior to which he was a nobody in the public eye, is commendable. Yang successfully distinguished himself from other candidates, and continues to do so, as his rhetoric has earned him labels such as “Silicon Valley’s candidate” and “The Internet’s Favorite Candidate”. His appearances have generated over 10 million views on The Joe Rogan Experience, The Ben Shapiro Show, and Real Time with Bill Maher. Clearly, Yang’s talking points related to the perils of widespread automation are shared by many others. Not only those at the forefront of AI technologies, such as Elon Musk and Jack Dorsey, have endorsed Yang’s policies, he also seems to appeal to a very large audience through the power of the Internet. Public figures like Yang are tasked with, and to some extent are, using their influence to raise awareness and enact policies about the potential impact of technology on the future of jobs.

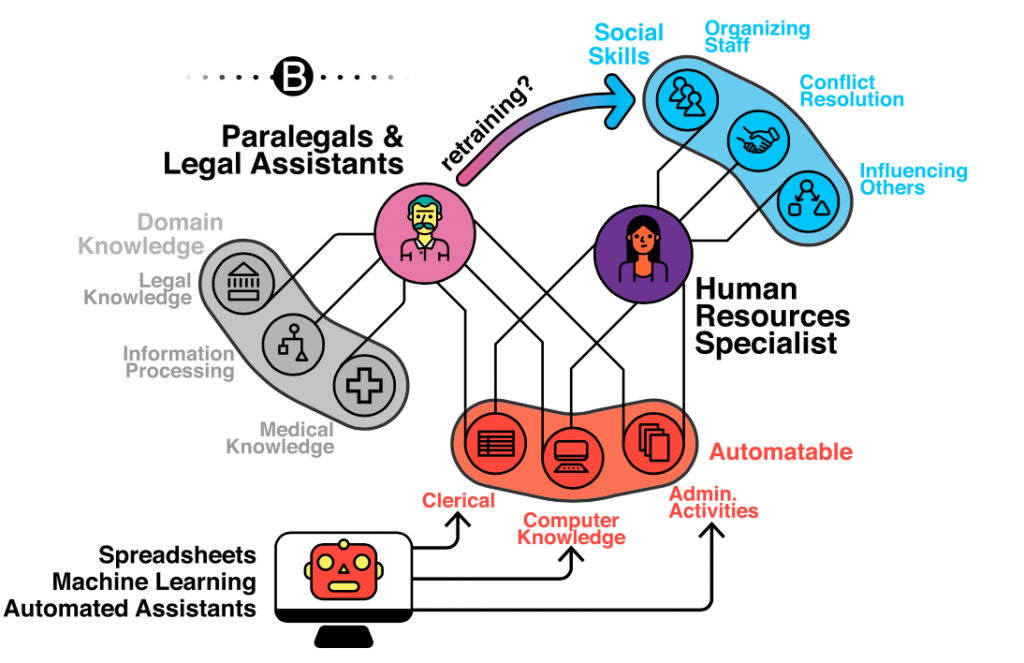

Besides fighting for policies such as universal basic income, how might we prepare for this wave of automation that we so fear? It is very important to understand exactly which skills are being replaced by automation. Especially for policymakers, who only with clear information on what awaits us can make informed decisions on how best to support workers and businesses through this revolution. Many jobs require the mastery of a multitude of skills and the execution of tasks that employ these skills concurrently. Machines will be able to perform some of these skills, to the extent that they can be coded and automated, but not all of them. In a scientific article published in 2019, Morgan Frank et al. argue that detailed, high-resolution data into skill demand trends and labor dynamics (assessment of worker mobility based on their skillset) is necessary to forecast and combat the risks of increasing automation. With a clear breakdown of skills that are in demand and those possessed by each worker (which is data that is admittedly not so easy to obtain), workers can be successfully supported in devising a new career trajectory.

Public figures like Yang are tasked with, and to some extent are, using their influence to raise awareness and enact policies about the potential impact of technology on the future of jobs.

Think of it this way: you could take a worker, have a list of skills they possess, identify the skills they have that machines can now perform, and given the skills they have that machines cannot perform and will not be able to in the near future, you perhaps direct them to another position or put them through a brief training to equip them with complementary skills that will render them candidates for another position. The aforementioned article provided the figure below to describe this process. It describes how a paralegal could go through a re-training procedure, while also using some of their pre-existing skills, to present oneself as an HR specialist who works in collaboration with AI.

The bottom line is that we should stop demonizing AI-based automation. When it comes to the threat of job displacement, we need to understand that this is something we can mitigate. Will some people be unemployed? Yes. Will there be minor destabilization in certain industries? Sure. But both these effects can be easily cushioned if we do our research and act in a timely manner. By properly preparing for skill automation in the ways listed above, we can facilitate a nondestructive introduction of machines into many sectors. As a result, with minimum damage, we can automate many tasks and reap the benefits of developing technologies.

Plus, why are we not seeing these radical changes in the job market as an opportunity to radically change our relationship with work? A re-evaluation of society’s understanding of work-life balance is long overdue. With AI and ML-based technologies, we might find that we can actually work less and keep productivity levels the same, if not increase them. When part of humans’ work is conducted by automated machines and/or algorithms, people can work less and still produce the same output at their jobs. If we can then evade the baleful pursuit of ever-increasing productivity, then we successfully will have brought about a vastly different work culture. Yes, that is a big “if” — but throughout history, technological advancements have always destabilized the status quo and precipitated major social change. Let’s heed the words of former professor and current economics blogger Noah Smith (a.k.a noahpinion):

Believing in technological progress is about believing in the potential of humankind. Do we really think that QR code ordering in restaurants will be the innovation that finally renders humans obsolete? Do we really think that wandering around a restaurant saying “Are you still working on that?” was the last thing that the average human being was good for, and after this we’ll never be able to find something new for people to do?

I don’t believe that. I believe we’re only at the beginning of our quest to unlock average people’s true economic potential.

Footnotes

1, 2, 3. Taken from Smith & Anderson, 2014