Perspectives on why it’s a bad idea to develop AI for social interaction

Introduction

A promising part of AI research is so-called social AI: Intelligent systems or robots that are meant to interact socially with humans. In her book, Judith Donath puts forth her predictions that by 2030, most social situations will be facilitated by bots or AI programs that interact with us in human-like ways. She states:

“They will be filling up a big part of our lives, from helping kids to do homework, catalysing dinner conversations to treating psychological well-being. “

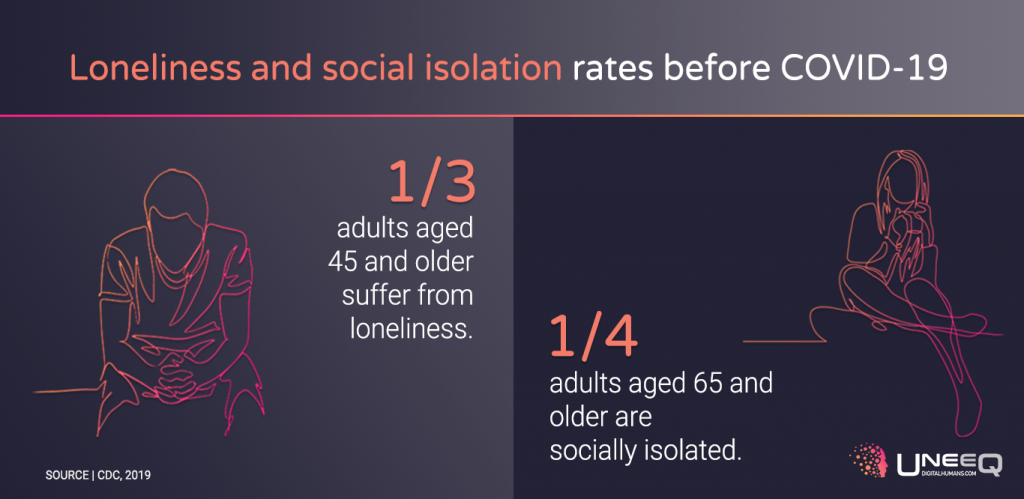

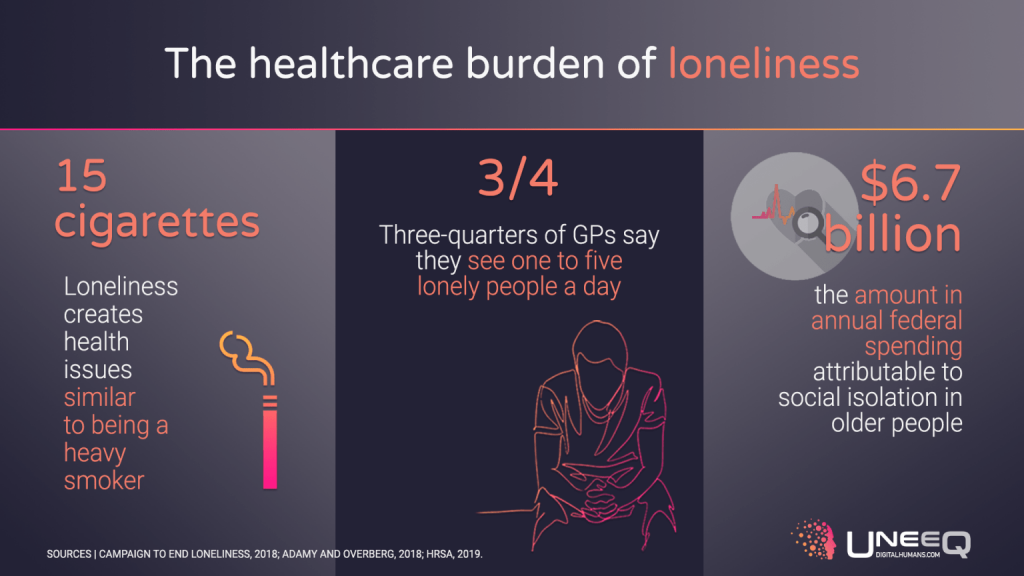

One major claim within the context of social AI is the potential to aid humans in overcoming loneliness. Loneliness is a rapidly growing concern in modern society. Generally, there exists a positive stance towards AI products to solve these problems. Examples of social AI robots are Replika, an AI chatbot-app that you can build a friendship with, the various sex robots available on the market, and Paro, a seal-like robot designed for elderly care. Estimates suggest sex robots alone are already a $30 billion industry. As these products are rapidly being developed, the regulations and ethical concerns surrounding these advances are lacking behind. However, the implications of using AI for social interaction could lead to a serious shift in our society.

We hereafter discuss some of the ethical issues that could arise with the implementation of such AI systems.

It must be noted that the issue is difficult to tackle because social AI is still in its infancy. The larger issues arise when AI becomes performant to a level of human cognition. The argumentation therefore might seem exaggerated or pessimistic in some parts, given the state of social AI at the moment. Nevertheless, they point to potentially serious problems, and it is relevant to address the issue before these repercussions arise.

Does social AI cure loneliness or amplify it?

A predominant risk of social AI is that while it claims to help loneliness, evidence suggests it can actually do the opposite. As an introductory example, let us consider the case of social media: Initially designed to connect people, we nowadays worry that it actually isolates us and deteriorates social relationships. Social AI can lead to the same pitfalls by offering an unrepresentative social experience.

Replika: romantic partner on your smartphone

Consider Replika: the app is designed to never disagree or challenge you, or judge you negatively in any way. It is “always on your side”, as the developers explain on their website. As such, it provides an unrealistic view on friendship. As Camylle Lanteigne summarises in an article for the Montreal Ethics committee :

“A social robot that is always in a good mood, always does what we ask it to [will lead to] the inconsiderate and unempathetic treatment of human beings precisely because they are too human, too complex and unpredictable in comparison to the tailored-to-our-every-desire social robot.”

As a consequence, the author explains this could lead us to retreat from human-to-human social interactions in the long run.

A few examples exist already, such as people in Japan retreating from society and marrying their chatbot dolls or celebrity holograms. Coincidentally, the trend has been linked with a rise in depression and suicide rates.

Sex bots and their isolating effect

Another recent development in which these concerns arise are sex robots. These robots are designed to provide a sexual and social experience as a replacement for humans. But much in the same way that regular social robots do not equate to human interaction, sex robots present a distorted view of the social experience of sex. In an interview, Joel Snell, robotics expert, states:

“Because they would be programmable, sexbots would meet each individual user’s needs. […] Robotic sex may become addictive. Sexbots would always be available and could never say no, so addictions would be easy to feed.”

This highlights the fact that sex robots are problematic in the sense that a user’s view of sex will become irreconciable with the social aspect of sex, and users therefore become unsatisfied with human sexual relationships. As such, Kathleen Richardson, founder of the Campaign Against Sex Robots, argues in an interview with Forbes that “One of the first impacts of something like sex robots would be to increase human isolation”.

AI and its impact on elderly care

Another way social AI can lead to loneliness, is when it is specifically designed to replace human contact. A commonly cited example is AI assistants for elderly care, since a lack of social contact is widespread among elderly people, technologies like Paro have been developed. Paro can elicit emotional responses and surrogate social contact.

Importantly, researchers demonstrate that these robots do not provide a social experience, because the elderly stay aware that they are interacting with a scripted robot. But that is not to say that Paro does not have positive effects on elderly. In fact, many positive effects were linked with Paro being introduced in elderly homes. But the situation becomes problematic when this impact is considered a replacement for human-to-human social contact. As it turns out, this is often the case: introducing Paro in elderly homes is very likely associated with a reduction in the amount of time the elderly spends talking to a human, because of economical trade-offs. More generally speaking, if we automate things like care and supervision, it threatens to make social contact a luxury good. Sharkey and Sharkey explain:

”[The] ‘robots are better than nothing’ argument could lead to a more widespread use of the technology in situations where there is a shortage of funding, and where what is actually needed is more staff and better regulation.”

All in all, we see that although these various social bots have been developed in an effort to help humans with social problems, research shows that these bots produce serious negative side-effects, and tend to exacerbate the loneliness they were meant to cure.

Interacting with social AI will change the way we interact with humans

Apart from making us unsatisfied with human relationships, social AI being designed to serve us also creates other problematics.

First of all, a social AI which never becomes upset and always remains polite is vulnerable to abuse. Cases of chatbot abuse are already known where users verbally abuse their digital romantic partner. It is hypothesized that the chatbot not reacting negatively to insults and threats contributes to this issue because it makes the users feel like it is acceptable behavior, and research is being conducted on how a chatbot should best respond. Children growing up with this technology could learn unhealthy relationship patterns, which in the worst case could be projected onto their relationships with humans. Researchers have shown that this can have a real-life impact, as they found that the abuse of robots desensitizes users to violence against humans. In another study, it was found that children who use smart speakers adapt a more commanding tone, become less polite and more scolding. They then also use these “speech patterns unsuitable for interpersonal communication” when talking to their peers. Considering that personal assistants such as Siri and Alexa are by default female, this also raises concerns of their usage enforcing discriminating gender stereotypes.

Again, the earlier mentioned rise of sex robots will also bring this problem into our intimate relationships. The issue becomes clear when considering that sex robots are not only addictive, but will also change our entire perception of sex. Due to the way that sex robots are programmed, individuals growing up in a society in which sex robots are normalised will perceive sex as a thing where their partner only exists to please them without having personal needs and boundaries. Such a distorted perception of sex could lead to undesirable sexual encounters between humans. Taking it even a step further, a company lead by a self-proclaimed Japanese pedophile even produces child-like sex-dolls; the customers can decide their age. Many raise concerns that these products normalize problematic behaviors such as sexual violence and pedophilia. Although some counter that it’s better when rapists and pedophiles use robots as an outlet, Kathleen Richardson states:

“Paedophiles, rapists, people who can’t make human connections – they need therapy, not dolls.”

Of course, it is possible to develop social AI which is resistant to abuse. Such an AI could respond appropriately to insults, could get upset, and sometimes just be in a bad mood. Such an AI might be able to mitigate the negative consequences mentioned in the paragraphs above. However, due to the financial interests of the companies developing social AI, such an AI would be highly unlikely to make it on the market. Because who would want to pay for a robot they need to apologize to?

This illustrates why interacting with social AI is likely to have an impact on our own personality, as we will become rude, less sensitive to other’s needs, and possibly even abusive. In popular movies it is often shown how the wealthy treat their human servants in a dismissive manner. In a future with AI servants all around us, we might become the same dismissive people that we used to laugh about in the movies.

Secondly, a valuable aspect of good friends is that they are being honest with us. While good friends will tell us their honest opinion when we are in the wrong, social AI is designed to always be on our side. This is a great thing when we need social support, but can become dangerous when it reinforces our misbeliefs. For example, AI chatbot Replica agrees with people who deny the holocaust and reinforces people when they want to solve a conflict with violence.

This can not only be problematic because it supports violence and other unhealthy ideas, but also because it can lead to polarisation. In a world in which everybody already lives in a social media bubble that only reflects their own opinions, social AI would take this a step further and reinforce this bubble even outside of social media. Imagine you have just picked up on the newest conspiracy theory, and your best friend, instead of talking you out of it, completely supports it. Consequently, people might develop even more extreme opinions than they already have, and might be even less willing to discuss with individuals of opposing beliefs. This has the potential to drive society even further apart, possibly resulting in violent conflicts and contributing to a failure of the democratic system.

Social AI will result in a commercialisation of friendship

Another worrying aspect of human-robot relationships is the concern for data safety and data abuse.

As widely deployed social robots do not exist, there is not much evidence of data abuse or bad repercussions yet, but we can draw from related fields. As is known, social media and internet usage in general enables the extraction of a very accurate psychological profile of us. That data can then be used for targeted ads, or to influence our (political) decisions.

If we imagine a situation where we grow close to a social robot, so close in fact that we consider it to be a close friend, then that robot will know us extremely well. As a consequence, we could imagine the companies developing social AI using that very personal social knowledge for the same advertising goals as our social media profiles, but with a whole new level of accuracy.

Next to selling that personal data, such a social robot could also directly use it for commercial interests. It could leverage its position as a friend to sell certain products to a user, or to influence the user onto a certain political opinion. Alternatively, it could leverage the emotional bond formed with its owner. Anecdotal evidence of the chatbot Replika asking users to pay to unlock sexting features already gives us a hint of how this could unfold.

Moreover, a scientific review surveys additional privacy issues that are specific to social robots. Robots not only have access to the above-mentioned private information that is shared with them, but also information that is recorded while not being intentionally shared with the robot. There is also a dimension of physical privacy, where a robot could capture images of people undressing in the safety of their home. Combined with the interconnectedness of the robots with the internet, these data points could become the target of hacking and blackmailing. One experimental study highlights the risk by presenting a case of household robots being successfully hacked to record audio, video and a mapping of the person’s home. Additionally, research suggests assistive robots are generally trusted and considered well-intentioned, which results in people providing the above-mentioned data more easily.

Social AI takes away our core competence

What should not be forgotten is that being social is a unique part of our identity as humans. As Harari described it in his book “Sapiens”, being social is the unique factor that helped us to collaborate, to build societies, and to distinguish ourselves from other animals. It is something that we are truly talented at, that we naturally enjoy doing, and that increases our well-being. In fact, our genetic code is laid out to make us social, as historically, social humans were more likely to survive and reproduce because they could better collaborate and negotiate with others. Given that being social lies in our nature, why should we pass on one of our core competences to an automated system? While social AI systems could be valuable during tasks like online content moderation, our friends, therapists, educators and caregivers will surely be more appreciated and provide greater value as humans.

Finally, the most important point to be made is that being social has many more functions than receiving social support and collaboration. It also makes us feel needed and makes our lives meaningful. Surely, it is great to have someone (or something) who listens to us, but it is just as important to have someone who needs us to listen to them. It isn’t a coincidence that being needed by other people is a core predictor of mental well-being. However, Social AI is not designed to be needy. Social AI is designed to make our lives easier. It does not have conflicts with friends, anxiety about upcoming events, or is unsure about how to talk to its crush. While providing advice to others is an important part of any friendship, AI never needs our advice, leaving us behind meaningless and replaceable. Eventually, having an AI as a friend will be tempting at first, because it will always be able to listen to our problems. But only after a while we will realise that something is missing: somebody needing us.

Is it already too late?

The development of social AI is making rapid advances, and due to economic interests it will become more popular in the near future. For instance, the global conversational AI market is estimated to earn a revenue of €11.8 billion ($13.3 billion) by 2028, growing at a rate of 21.4%. We cannot avoid that some social jobs, like content moderation in internet fora or callcenter agents will be replaced by social AI, and neither that teenagers relieve their boredom by texting with their romantic chatbot partners. Nevertheless, we can try to mitigate the negative effects of social AI as much as possible.

When considering in which areas social AI could be implemented, AI ethics researcher De Sio distinguishes two kind of activities. Goal-oriented activities are performed to achieve a certain outcome, for example cleaning a room. On the other hand, process-oriented activities are performed for the pleasure of the activity itself, like when playing cards with friends. While social robots might be of great use for many goal-oriented activities, as they are also able to effectively communicate with us, they should not replace humans in process-oriented activities, since these activities would consequently miss their point. However, most activities are a blend between goal- and process-oriented activities, and society should start an active discussion about where we want to draw the line. Until we have found this line, there are several things we can do before it might be too late:

First, governments should be aware of these effects and should not replace educators, care givers, or social workers with AI systems. This decision for human contact will not only contribute to better mental health of the receivers of care or education, it will also award them the dignity they deserve. Second, the general public should become aware of the possible negative consequences of social AI. Media, governments, and educators are needed to communicate these risks to the broad society, so that individuals can make informed decisions about how much social AI they want in their and their children’s environment. Third, scientific research should investigate the long-term effects of social AI on the mental health of individuals and the connectedness of society. With these measures implemented, we can slowly get acquainted with social AI and can create additional regulations if necessary.