“The changes are so profound that, from the perspective of human history, there has never been a time of greater promise or potential peril”

Klaus Schwab, author of The Fourth Industrial Revolution

Humanity is experiencing a time of rapid technological development. Advances in Artificial intelligence (AI) and its ability to augment automation are seen as the beginning of a new industrial revolution. Similarly to the advent of the steam engine, mass production, and IT systems, this new wave of AI empowered innovation is stirring up public discourse about what the future of work will hold for humanity. Which jobs will thrive and which ones will wither? Will there be jobs at all? The uncertainty and stakes are high, but who to trust for information? While Silicon Valley’s CEOs hype their newest AI tech on glamorous stages, promising a prosperous and better world, newspaper watchdogs and science fiction pieces often cultivate a dystopian narrative characterized by human obsolescence and inequality as AIs will steal our jobs. Scientists and experts have criticized this polarization of the debate and called for more nuance. In this vein, we argue that the fear about AI’s impact on the job market is vastly exaggerated, yet, not to an extent where we should blindly trust the AI hype without taking precautions.

The Employee of the Millennium Award Goes To: AI

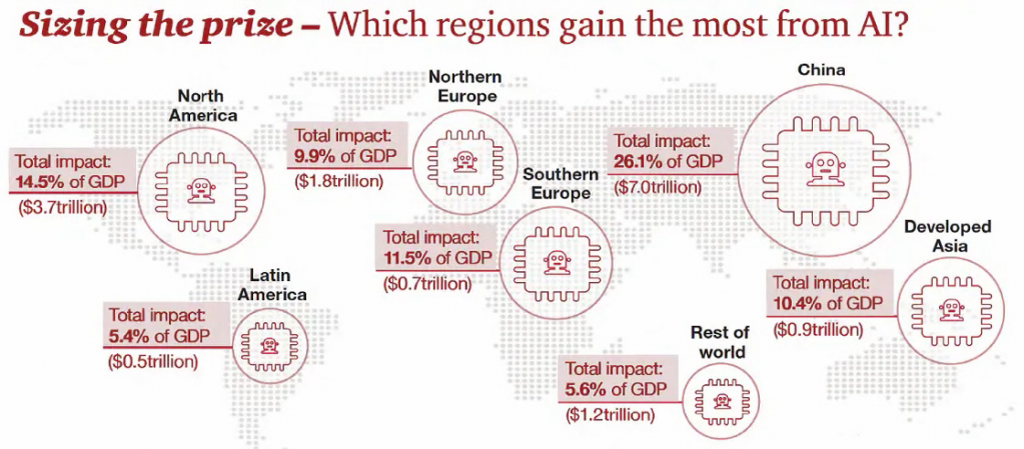

Steve Jobs described his vision for computers in society as “a bicycle for our minds.” Humans are inefficient when it comes to moving from place A to place B, therefore humans require more calories than many other living organisms to move the same amount of weight. However, with a bicycle, people can move more efficiently than other living organisms. Steve Jobs understood the potential that computers had and nowadays, AI could have similar implications for the efficacy of the human mind. The potential that AI brings is a game changer and its tremendous influence on the global economy and the local workplace cannot be denied any longer. Firms who have already started to adopt AI solutions boosted their revenues by about 15%. By 2030, PwC expects AI to contribute up to $15.7 trillion to the global economy of which $6.6 trillion is likely to come from increased productivity.

These numbers suggest that AI may exceed human employees in their performance. When comparing ourselves to AI, it often dominates us in physical and sometimes cognitive aspects. According to research by University Hospitals Birmingham, the average incidence of a medical diagnostic error by an AI system is estimated at 14%, which outperformed healthcare professionals with an error estimate of 13%. In manufacturing, 23% of all unplanned downtime is the result of human error, in telecoms this was 50% of the time. Adding to this the Mars Climate Orbiter: a $330 million dollar spacecraft that was destroyed because of a failure by scientists to correctly convert between metric and imperial units of measurement, a peak of human fallibility. Humans tend to overestimate the importance of what we know, and underestimate the effects of what we do not know. We see patterns where there are none. We tend to give more weight to recent events, and confuse chronological order with causation.

Moreover, AI is growing our productivity and making us more efficient by taking over tasks that are extremely dangerous. On the one hand, this can liberate humans from hazardous manual labor, thus giving them the chance to apply the same discipline in other jobs that are safer for them, such as tasks involving empathy and creativity. On the other hand, it can make dangerous work more secure. The article “How Robots Are Saving Humans From Doing Dangerous Jobs” gives a very good example of how firefighters depend on robots to assess burning buildings. The firefighters use an AI robot called SmokeBot to assess and map the damaged interior using thermal cameras and gas sensors. This way, it is easier for them to prepare or call for more assistance when needed.

Currently, we are already seeing the physical embodiment of the potential of productive AI. Next year, Elon Musk, the CEO of Tesla, will release the prototype of the Tesla Bot which will exemplify how AI can be designed to eliminate dangerous, repetitive and boring tasks. Things like bending over to pick up something and going to the grocery store would become things of the past, especially for the older generation. Essentially, the future of physical work will become a choice rather than a must.

“Thanks, We Already Found The Ideal Candidate” – The Supposed Rise Of A Useless Class

The above shows that AI promises many advantages for the future of work. However, the expansion of tasks in which AI becomes superior to human performance has elicited fear in society. If you were to believe Yuval Harari, historian and best-selling author of Homo Deus, AI will push most people out of their jobs. As many humans will become unable to compete with the benefits AI is promising to CEOs and investors, they will be enticed to give our jobs to intelligent software, chatbots, social service humanoids, and manufacturing robots. Indeed, BlackRock, the world’s largest investment manager, already replaced several portfolio managers with AI to reduce fees for investors. And who could blame them? It’s nothing personal, it’s business. Yet, our work tends to be deeply personal as it fulfills our needs to connect, change, and create. So according to Harari and the popular fear-narrative, the more advanced AI becomes, the more we will see the rise of a “useless class”: People who will have lost their source of income and possibly meaning-making. Given these dystopian pictures conjured in the public debate, it is not surprising that 37% of workers fear the advancing AI revolution could take their jobs by 2030, with rising tendency. Not only does Harari expect their financial power to evaporate but with it the elite’s concern for their human rights and increasing social issues.

The fear narrative is often justified with economic consultants’ expectations of potential job automation in the future. Admittedly, estimates such as PwC’s of 30% of jobs being automatable as early as the mid-2030s, does not suggest an all rosy future at first thought. Especially, if you dive deeper and realize that especially those who find themselves in an already economically vulnerable situation are said to be affected four times as much. That is the low-educated who often hold repetitive and routine occupations, such as in manufacturing or construction, but also in services such as retail or hospitality. This seems to put developing countries with large low-skilled workforces in an especially dire position. While the unemployed in rich countries might be able to get support while re-educating for a new job, the developed world will not offer comfortable welfare cushions to those whose jobs are reshored to AIs in developing countries.

AI & You – Fierce Competitors or Friendly Co-Workers?

So should we really be scared of AI replacing us at scale? Scientists have frequently criticized dystopian portrayals of mass replacement by AI as exaggerated. It simply lacks context, so let’s explore the less clickbaitable side of the debate.

While we cannot be certain how much work exactly will be automated with AI, NGOs, scientists, consultancy firms, and experts all agree on one thing: AI will not lead to mass unemployment. There are three main reasons for this.

Firstly, the possibility of AI augmented automation does not tell us anything about its actual deployment in the foreseeable future. Many technological, economic, social, and regulatory and legal questions need to be answered beforehand. These include questions of profitability. For instance, scientists argue AI driven automation is often unprofitable in the developed world, as investment is costly due to regulations such as intellectual property rights and data ownership. While investment in AI is much less capital intensive in developing countries, local labor is considered too cheap to make further automation attractive. However, such countries will need support as their workforces’ wage bargaining power will diminish and incomes may start to stagnate. Another illustrative example concerns the highly praised autonomous vehicle. PwC anticipates the technology to put over half of transportation jobs at risk by the mid-2030s, yet, the OECD sees many barriers to such early adoption. In case of accidents, ethical decisions must be taken (e.g. should the car hit a child or sacrifice the safety of the elderly passenger inside?), but also legal challenges concerning liability arise (i.e. who is responsible for the accident and the decisions taken?). Such problems may actually lead to societal rejection and therefore hinder quick adoption, prompting the Boston Consulting Group to predict a share of only 10% of such vehicles by 2035.

Secondly, even if AI automates most tasks of a job, this does not necessarily imply that these do not need human assistance anymore. For instance, humans will still be needed to oversee automated processes and ensure their proper functioning, thus redefining rather than replacing human jobs.

So while about half of our work time is spent on automatable activities, by 2030, we are not likely to see more than 15-17% of work time to be replaced by automation. Elon Musk’s ambitious attempt to fully automate a Tesla factory illustrates this nicely. While robots were able to take over most tasks, they were not able to deal with even slightly unexpected situations at the assembly line without human assistance. Musk’s response mirrors what experts have expected all along:

“Excessive automation at Tesla was a mistake. To be precise, my mistake. Humans are underrated”

Elon Musk

Thirdly, experts and researchers see AI augmented automation as a necessary means to deal with the continuously increasing amount of work, which is partly stemming from aging populations and the exponential explosion of data. In fact, scientists anticipate that over the next 35 years, demographic changes in the G20 would require 130 million full-time employees to just keep up the present GDP per person. To reach projected targets this number would even increase to 6.7 billion.

All this is not to say that AI might not actually eliminate some jobs entirely, especially in the long term. However, the effect of AI on the future of work does not only involve work automation but also job creation which we expect to balance out the jobs lost.

AI is Hiring: Trainers, Explainers, Sustainers – Apply Now!

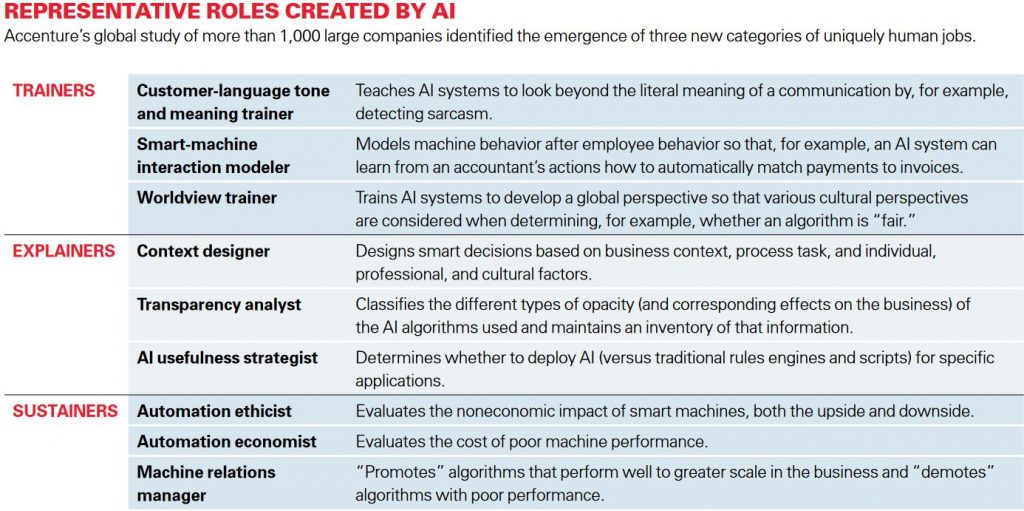

Indeed, history has shown us that technology more disrupts than destructs the job market. A recent report of the MIT’s Task Force on Work of the Future echoes this insight, and stresses that 60% of today’s occupations just emerged during this last generation. Think of the invention of the smartphone which amplified the use and importance of social media and thus brought forth an army of creative social media marketers and influencers. Experts are sure AI will also spur the creation of new jobs. By 2030, already 8-9% of people could be holding new futuristic jobs as a result of AI automation. While this may come as a surprise to many, STEM skills might be important but not a prerequisite to gain a job requiring human-machine collaboration. Instead, MIT researchers find that excellent soft skills will distinguish the successful applicant. These include creativity, complex reasoning, sensory perceptions, and social and emotional intelligence. Be ready for new fancy job titles, such as trainers, explainers, and sustainers. Trainers will be the educators of AI, making them perform as they should, and teaching them how to mimic and understand the complexity of our human behavior. Explainers will become the middlemen between AI tech and non-technical decision-makers. They will communicate the seemingly mysterious workings of AI and evaluate their usefulness in specific contexts. Finally, sustainers will become the watchdogs of AI systems, checking that they work according to plan and will ring the alarm when unintended consequences arise.

Is The Promise Of New Jobs a Lie?

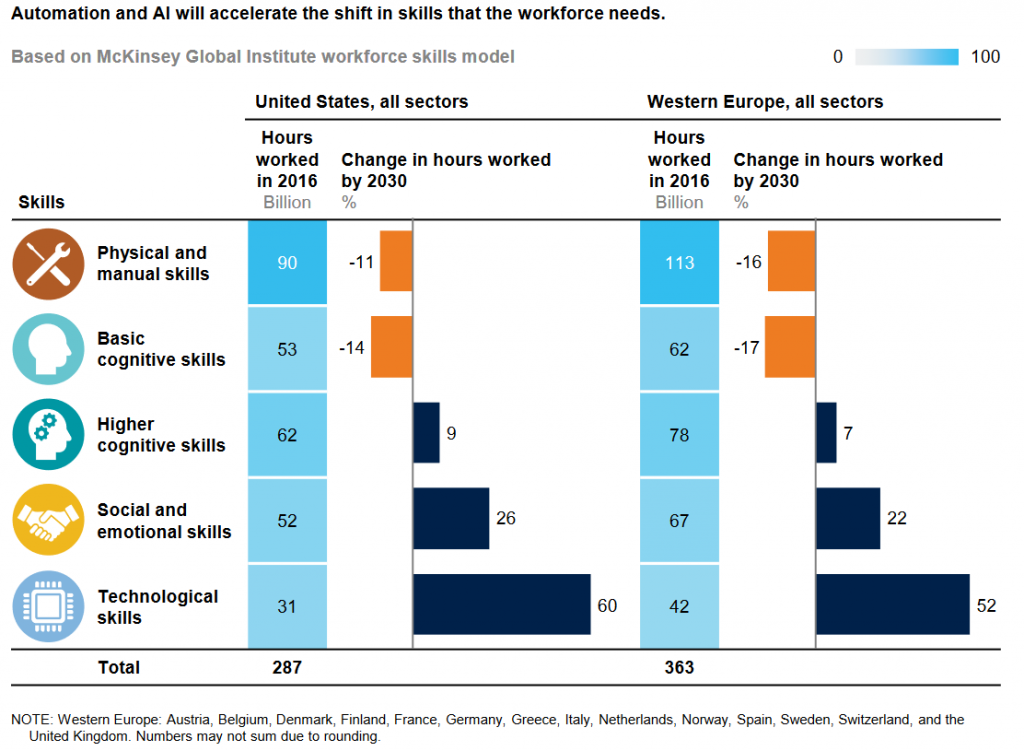

However, there is fear that new jobs created by the deployment of AI are limited to the field of technology, accordingly requiring a highly technical skillset. Therefore, AI’s promise of new employment opportunities is often met with sarcasm as many expect such jobs to go to privileged and highly educated people. To qualify for such professions or jobs less prone to automation, 120 million people might have to expand their skills or retrain to acquire a completely new skillset to match the demand.

However, for those who lack financial and cognitive resources to adapt, such retraining is seen as very difficult to nearly impossible. History has proven worries about technological unemployment to be exaggerated, yet, the reason why human labor has prevailed relates to its ability to acquire new skills. This will become increasingly challenging as new work seems to require an even higher degree of cognitive abilities. Subsequently, this group is feared to be left behind in the sheer never ending race against the improving capabilities of AI. Adding to this concern, is the observation that the majority of the workforce in developing countries belongs to this group which could reinforce global inequality.

The Diversity of Future Jobs

Such worries are not completely unjustified. For some adapting to the AI disruption of the economy will be more difficult than for others. Yet, it is a simplification to claim that AI deployment will not bring about a diverse palette of employment opportunities.

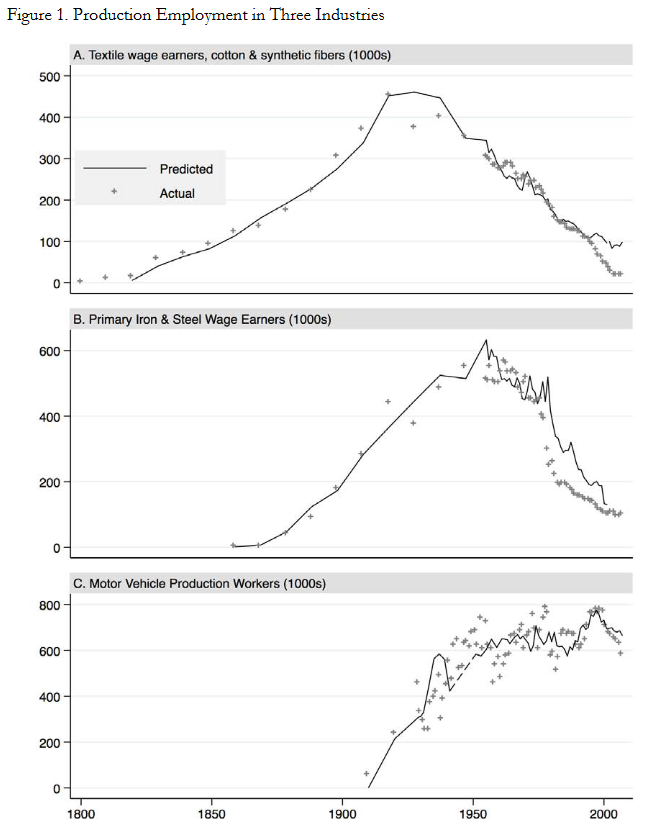

Paradoxically, more automation may lead to more jobs in the same sector. In recent decades, technological advancements have resulted in a significant reduction in industrial jobs. However, prior to that, employment rates rose for nearly a century, even in industries undergoing significant technological growth. During this time, demand used to be very elastic at first and then became inelastic, and the effect of AI on jobs will in a similar way depend on the nature of demand. The industrial example demonstrates that the impact of technology is more intricate than the simple narrative of ‘automation causes job losses’ in affected industries. The underlying illustration shows how different manufacturing sectors experienced a significant employment growth in the same time period as when they experienced productivity growth.

Overall, these industries have gone through more employment growth than job losses. This is due to newly developed technology not replacing labor completely with machines, but instead reducing prices, and improving product quality, speed, and delivery. Taken together, this can increase demand and with it employment, even if the human labor required per unit output may decrease. In addition, cheaper prices imply more disposable income to spend, so even sectors not prone to automation (e.g. the creative industry) may see new diverse jobs suitable for various skill levels, as long as they are in demand.

Additionally, further deployment of AI will also create new jobs for people in developing countries. For instance, the data labeling industry is one of the newly founded industries with high potential regarding these countries, to the extent that it produces new low-skill job opportunities as 80% of time invested in building AI systems consists of human labeling work. This supports the view of current AI researchers that new jobs that are created by AI are not only going to be related to technology and high skilled positions.

Disruption Instead Of Destruction – But What Next?

In conclusion, we see that neither exessive fear nor uncritical hype is the correct response when pondering about the effects of AI on the future of employment. Yet, the positives seem to clearly outweigh the negatives. Unlike often feared, AI will not steal our jobs and make us obsolete. Instead, our work will change and we will have to welcome AIs as our new co-workers. The productivity boost that will result from this will bring about new, safer jobs, in tech but also in other demanded sectors. As James Manyika, director of McKinsey puts it:

“It’s natural to wonder if there will be a jobless future or not. What we’ve concluded, based on much research, is that there will be jobs lost, but also gained, and changed. The number of jobs gained and changed is going to be a much larger number, so if you ask me if I worry about a jobless future, I actually don’t. That’s the least of my worries.”

James Manyika, director of McKinsey

So we should see AI as a disruption rather than a destruction of the job market. But like with every market disruption, there will be some who struggle and will require the support. That might be the manual workman, who struggles to retrain for a new job, or developing countries whose wages could stagnate. How can we address these issues? Three solutions are frequently mentioned in the debate. Firstly, labor mobility requires lifelong learning opportunities. Yet, we see surging costs in education, rising student debts, and a monopolization of knowledge and privatization of higher education. Accessible education throughout life must become the norm. This should be provided by states but also companies must further invest in the retraining of their workforce. Secondly, universal basic income and possibly also services (e.g. free transport) may have to be implemented to support people on a job transition journey and those who might not be able to find viable employment. Finally, the policies must be established to share access to patented AI applications. At the moment, we see a monopolization of AI patents, mainly by the US and China, yet, especially developing countries need better access to AI to ensure their further economic development.