The popular view that the gravest danger posed by AI is a singularity event that results in AI superintelligence and human redundancy is largely unfounded and misleading. The true danger flowing from AI is its potential abuse for purposes of psychological profiling and social engineering, notably to advance state power and/or corporate interest.

There is a persistent view, popular especially among highly respected innovators like Elon Musk, Ray Kurzweil and Masayoshi Son, that some sort of AI ‘singularity’ event is imminent. By this, they mean that AI will inevitably surpass human intelligence and render the latter essentially meaningless. Kurzweil and Son even put a date on this event, which they claim will happen sometime around 2045. A grave danger in this scenario is posed by the fact that we could lose control over AI and have no means to influence its moral compass. Musk even warns of an AI immoral dictator that could forever enslave humanity. Son says that humanity should seek a collaborative relationship with the superintelligent AI and Kurzweil even goes so far to suggest that AI will be the spiritual masters and priests of the future. In our humble opinion, these views are largely based on speculation and an insufficient understanding of what ‘mind’ even is. They could also be dangerously misleading, in that they distract the public attention from the more imminent and real dangers posed by AI, which is its potential abuse for purposes like social engineering and psychological profiling. While the innovators above are certainly brilliant men, they should not be in charge of deciding what society should focus on when facing the dark side of AI.

Why an AI singularity event does not pose an immediate threat, and may indeed never occur.

While the views shown above are interesting to ponder over, they are ignorant of a few key facts, most notably, (1) there is no indication if or how a task-independent, ‘general’ artificial is technically possible, (2) the scientific knowledge on what constitutes consciousness, and hence true agency, is far from conclusive, and there is as yet no indication that something akin to human consciousness can possibly be constructed via computational methods, (3) similar arguments also hold for morality and a range of other features that constitute human intelligence and experience, which is poorly understood for humans and much less so for artificial agents. AI engineers, in particular, should be aware that those technologies that make the news for their supposedly intelligent behaviour, for instance, deep neural networks or certain reinforcement learning algorithms, operate mainly on the basis of sophisticated statistical, mathematical and computational methods. This is to say they operate algorithmically, meaning they are bound by certain mathematical-logical axioms and the nature of their design. To put it yet differently, no AI engineer would seriously consider that the neural network he has developed will suddenly be inclined to disobey his orders and commit some sort of nefarious deed, like taking over his e-mail account. This relatively simple insight might prove to be crucial because upon closer reflection it should be fairly evident that there is no strong evidence for the claim that higher forms of intelligence process in this algorithmic fashion. It is certainly not what accords with the subjective experience of most people, and many folks would passionately disagree if one were to suggest that their latest brilliant insight was a mere side-product of some misunderstood algorithmic process. Indeed, recent research rather suggests that instead of an algorithmic one, the human brain reflects a highly chaotic and complex system. Understanding the brain as a chaotic system implies that proper replications of its many functions may be a task vastly more complex than is assumed in the singularity scenario.

The views expressed by the thinkers above reflect what has become mainstream in the philosophy of mind, namely the computational theory of mind (CTM). This theory is strongly reflected in disciplines like cognitive psychology, and it operates essentially on the analogy that the human mind operates like a computer, with information being its primary currency. Within the scientific community, there is considerable disagreement about what the CTM entails, some suggesting that it is merely a convenient metaphor while others go so far to claim that the human mind is literally equivalent to a digital computer built on biological structures. As Steven Horst describes in great detail, there are a vast amount of inconsistencies and ambiguities inherent in the CTM relating to notions like representation, symbol, meaning, and intentionality. To say the least, there is no reason to believe that CTM conclusively bridges the philosophical gap between mind and machine. A common critique against CTM, for instance, that put forth by the physicist Roger Penrose, is based on the Incompleteness Theorem formulated by Austrian logician Kurt Gödel. A simple analogy of Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem is the phrase this sentence is false. One does not need to be a logician to deduce that if it is true, it is false and if it is false, it is actually true. Gödel has shown conclusively that such paradoxes are an existential part of mathematical systems, once and for all shattering dreams of contemporary mathematicians like David Hilbert who aspired to describe the entire universe in terms of mathematics. Later thinkers like Penrose have taken this argument further to entail that indeed the human mind cannot just be composed of simple logical operators (e.g. the neurons that flick on and off), but that there has to be some trans-logical functionality to the human mind by the virtue of what it can achieve. Has not Newton been inspired for his gravitational theory by the apple that fell on his head, or was it rather his search for a perennial truth in the biblical texts that caused things to ‘click’? It is an unspoken truth that innovations and the scientific process often tend to come about through dreams, intuitions and sparsely related thoughts, the seemingly irrational parts of human intelligence, rather than rigorously operating within a fixed set of axioms. The human mind is vast and still largely uncomprehending structure, and we have not yet cracked the mysteries of life itself. It would be arrogant and foolish to assume that we have understood its workings and can easily engineer something that will far exceed it.

Of course, there are also arguments against this Gödelian approach. Most prominent is the argument that the human mind does not need to necessarily be one incomplete Gödelian system, but that it is constituted of several logical systems that are layered over each other to create the illusion of one coherent and consistent mind. There are also arguments that take a different approach to what AI superintelligence really entails. Most notably, some authors and researchers argue that AI may not resemble human intelligence, but rather be a different kind of intelligence. Hence, it may not be necessary to fully understand how human intelligence works to build an AI superintelligence, and the restrictions on logical structures imposed by Gödel’s Theorem could be circumvented by clever engineering. While AI may differ from human intelligence qualitatively, it may be more intelligent nevertheless, measured by common standards like the IQ. This may certainly be true, and if we count for instance the ability to solve mathematical questions as a measure of the human intellect, this is already partly true today. However, even with this proposition, the question arises why thinkers of the singularity attribute particular human traits to the approaching AI superintelligence. For instance, why does Elon Musk worry that AI will spontaneously develop a desire to build and control empires, as humans have done throughout history. Why does Ray Kurzweil fathom that AI agents may become spiritual teachers, without any indication that AI might mirror the human desire to establish religions and find answers to the deepest questions of its existence. Rather than rigorous scientific endeavour, it seems that such conclusions are more likely drawn from projecting human traits on something unknown yet mysterious like AI.

So while the arguments given above do by no means rule out that general AI might possibly exist in some form in the future, and that it may indeed exceed humans in most areas of what is widely considered to be hallmarks of intelligence (although those standards are constantly shifting), they show at least that the claims of an inevitable singularity are ultimately still of a speculative nature, with scant scientific evidence backing them up. While such speculations are fine in and of themselves, regulators around the world need to make absolutely sure they do not make those claims the centre of their policy initiatives. Especially the technological inventions offered to ‘solve’ the singularity problem, like Musk’s firm Neuralink, which investigates how the human brain can be linked up with a supercomputer, might end up as a trojan horse to exacerbate the much more real and imminent danger posed by AI.

What are the real dangers posed by AI?

While the views expressed above largely remain material for more abstract, philosophical discussion, there already exists plenty of evidence for how AI can be abused for purposes like psychological profiling and social engineering. The perhaps most dystopian outcome of this process would perhaps be that AI becomes an efficient tool that helps totalitarian states in their ambition to exert absolute control over their population (think about how the governments of Nazi-Germany or the Soviet Union would have appreciated the tools of modern AI at their disposal). While this worst-case scenario is perhaps not imminent, there are some disturbing trends that should be addressed immediately. In essence, AI should be regarded as a tool that can optimize a goal, and its potential for doing good or bad in the world is measured by what exactly constitutes those goals and who gets to define them. If the goal is defined by an authoritarian government, as for example ensuring that citizens do not hold any views that fall out of line with the official narrative, AI could be an efficient tool in achieving that goal. This would of course to the great detriment of humanity, but if anything history teaches us to not be complacent and think these things will not just happen. This paper addresses two key aspects of the problem of AI being abused for psychological profiling and social engineering, which are (1) its misuse by state actors to exert control over their population and (2) its misuse by corporate or political actors who seek to guide individual decision making processes.

1. Misuse of AI by state actors to exert control over their population

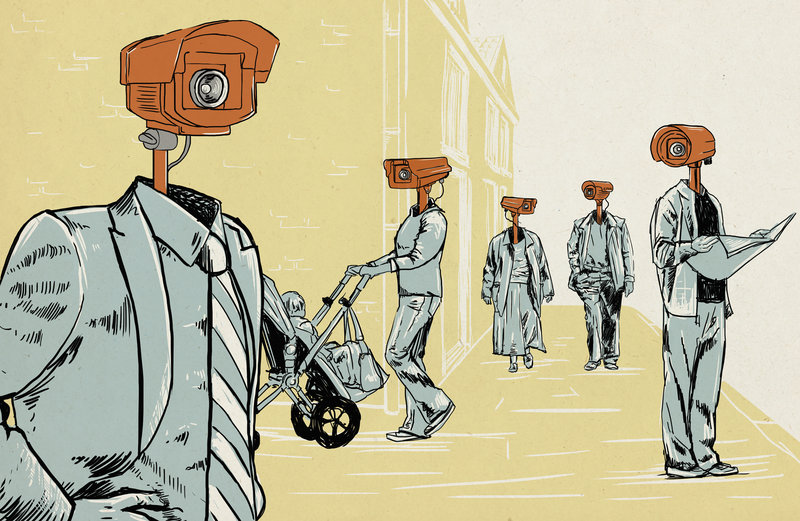

This variation is particularly tempting for more totalitarian leaning states that fear their own population, and hence have a huge demand to gain more control over their citizens’ lives. The People’s Republic of China (PRC), under the leadership of the communist party, is vocal about its ambitions to become a leading AI power over the next decades. It is also the nation that takes the lead in demonstrating how AI can be utilized to undermine any sense of civic liberty and advance the totalitarian control of the party-state. A strongly disturbing of this is given in the western region of Xinjiang, in which China uses AI technology for racial profiling of its Uyghur population, which are incarcerated into labour and indoctrination camps by the millions. Facial recognition software and computer vision algorithms are particularly useful are registering when a certain threshold number of Uyghurs assembling together is exceeded, at which point the state security can immediately increase supervision or intervene, to prevent any possibility of organized resistance against what many Uyghur people perceive as the Chinese occupation of their homeland.

Take the most risky application of this technology, and chances are good someone is going to try it. If you make a technology that can classify people by an ethnicity, someone will use it to repress that ethnicity.

Clare Garvie (nytimes.com)

2. Misuse of AI by corporate actors who seek to guide individual decision-making processes

While the misuse of AI by state actors to exert control over their population must also be taken seriously by liberal democracies, worst-case scenarios could so far be avoided through solid rule of law and an attentive population. Practices like that in China would generally not go well in the wider public, which tends to be more varied in state power. This is certainly true of many European countries, who still have in memory the existence of the Soviet system and its many satellite states, like the DDR in Germany. Eastern Germany, in particular, had established one of the most pervasive surveillance systems ever made, with around one-third of the entire population operating essentially as spies to the Stasi. Besides this, however, tech companies are already exploiting the possibilities of psychological profiling for commercial goals. Instead of plain propaganda messages, individuals are targeted by ads aiming to stir their consumption patterns in certain directions. While their goals are very different from those of authoritarian party-states, their methods for invading individual privacy also appear to be slightly more subtle. Facebook, for instance, used a VPN-app called Onavo to get insights into the data traffic happening on users’ phones. [24] Especially teenagers were targeted to participate in a ‘research project’ that involved downloading and installing the Onavo, which made their phone then essentially serve as a spying device. Facebook reportedly used this data to figure out how it can optimize user behaviour towards using more Facebook, and fewer competitor products.

The case of Cambridge Analytica showed that AI can also be highly useful in influencing and obscuring the democratic process. The company, which was formerly headed by Donald Trump’s chief election strategist Steve Bannon, harvested the Facebook data of millions of users to conduct psychological profiling, using big data analytics and AI. The scheme was based on a paid personality test called thisisyourdigitallife taken by hundreds of thousands of participants, which not only learned how to conduct psychological profiling but simultaneously collected data of the participants’ social network. Based on this analysis, individuals were targeted with political messages specific to their psychological dispositions. Cambridge Analytica turned this practice into a business model that finds attraction from political figures from around the world, for obvious reasons. Christopher Wylie, the guy who blew the whistle, neatly summarizes their work: “We exploited Facebook to harvest millions of people’s profiles. And built models to exploit what we knew about them and target their inner demons. That was the basis the entire company was built on.” Facebook remained strikingly passive throughout this entire process and only openly condemned Cambridge Analytica after immense public pressure has built up. The case illustrates how vulnerable the individual can be to the abuses of AI technology, even in democratic societies based upon the rule of law. If such things are not taken seriously, they have the power to seriously undermine the stability of democratic societies.

Why technological solutions to the singularity issue may exacerbate the real and more imminent threats posed by AI?

While there is nothing wrong with expressing the view that an AI singularity is imminent, there is a certain danger in the urgency in which technological solutions to fix the perceived problem are propagated. For instance, Elon Musk founded his company NeuraLink, which investigates ways of connecting AI technology directly to the human brain via decisively small cables, with the aim of allowing humanity to take part in the approaching arrival of superintelligent AI. Similarly, the company Kernel is conducting research into neuroprostheses with the aim of augmenting human intelligence and keeping up with AI. The company also investigates if and how the human neural code could be programmable. If such a thing would be possible, it goes without saying what kind of damage this type of technology can cause if it ever landed in the wrong hands (which history teaches us it most likely will). Observing the disturbing trends shown above, such technological ‘solutions’ may significantly exacerbate the more persistent and realistic danger of AI technology, which is its abuse for nefarious purposes like psychological profiling and social engineering. The great Russian writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, a survivor of the Soviet gulag system, once famously declared that totalitarian systems would always fail in the sense that regardless of how oppressive they might become, they were never fully able to penetrate the inner world of the individual. Endeavours like Neuralink and Kernel may just make it technologically possible to take away that limitation in the future.

The obsession with ideas like singularity also derails the conversation on AI and society away from the question that needs to be addressed more urgently, which is how do we regulate AI and make sure it is used by the right people for the right purposes? The questions of how by whom and for what goals AI will be used in the future are far more important than any speculations on whether AI can develop its own agency. Hence, a sound public debate and prudent implementation of regulatory bodies that protect the individual is urgently needed. It is also important to note that such technological innovations cannot be stopped, and they most likely will have numerous positive applications in the future, especially in the realm of curing mental disorders. However, their potential for abuse makes it imperative to regulate them properly and these developments should always be reflected on in an open public debate. This debate should be approached with a sense of realism. Next to futuristic vision, and perhaps genuine care about the prosperity of humanity, commercial interests are a key factor in determining the technological developments described above.

“The market for implantable neural prosthetics including cognitive enhancement and treatment of neurological dysfunction will likely be one of if not the largest industrial sectors in history”.

Bryan Johnson, the founder of Kernel

Rather than becoming mindless consumers, it is also each individual’s responsibility to reflect upon whether such markets reflect their sense of what it means to be human. If it does not, people are urged to resist this trend and inform their peers about the immense potential dangers. While private enterprises and their potential in unleashing creative destruction are an important, if not the key, driver of innovation, the case of social media companies has illustrated that pure business logic may not be sufficient in ensuring that these technologies are applied with what is best for society in mind. Hence, there should also be a broader debate on what role private enterprises should play in the development and distribution of AI technology.

Why there might be some hope that these issues will be addressed before it is too late?

This paper has focused on the more dystopian and dark applications that AI might bring upon humanity in the coming decades. This is not done to monger fear, but because those warnings are urgently needed in a debate that is often derailed by wild speculation and sci-fi scenarios. What also should be noted, however, is that besides the negative trends that are described in this paper, there are also a wide range of more hopeful developments that work towards making sure AI will benefit humanity rather than undermining it. Good work is done by the Future of Humanity Institute, an institute by the Oxford University that features multi-disciplinary scholarly work to stimulate an educated public debate. It is lead by Nick Bostrom, a leading scholar on AI and author of the book ‘Superintelligence’. It is important to engage different disciplines in this debate, as a psychologist might reach very different conclusion from an engineer on what the nature of AI is, and an ethicist might yet have another viewpoint. The Future of Life Institute, which, to his credit, received large financial support from Elon Musk, also offers stimulating content on AI safety research, global AI policy and lethal autonomous weapons. They acknowledge and explore both the immensely positive, as well as the potentially destructive effects that AI can have on humanity.

The most promising AI strategy to address these concerns is formulated by the European Union, with its strong focus on fostering “human-centered AI”. This strategy focuses on embedding AI within existing regulatory frameworks on human rights and human and societal welfare. This is done not only to protect individuals from nefarious conduct through AI abuse, but also to establish an architecture of trust in the development process itself. While the EU is often portrayed as lagging behind on AI technology, it remains the dominant norm-setting global power. This has the effect that many companies around the world work towards their products being compliant with EU regulation, as EU regulation is usually the strictest and that means their products can be shipped to Europe. If Europe maintains its standard setting function in the field of AI, at least internationally operating companies might be incentivized to align with its human-centered development approach.