Artificial Intelligence is a term arguably as popular as it is misunderstood. Riding on the idea of a Frankenstein’s monster, a creation escaping the whims of its maker, the notion of an AI going rogue or starting out as malicious has been a staple of science fiction. The machines seek to murder seemingly innocent humans, as in the Terminator, or to use humans as batteries, as in the Matrix. Whatever the particulars of the plot, the conflict is almost always between a cold, calculating machine (this is the capital), and a feeling, sentimental human. The machine is almost god-like, all-powerful and all-knowing, while the human is meek and helpless.

This trope has created a feedback loop in the common perception of technological progress of AI – the popular press often seeks to capitalize on the pre-existing fear of the machines overtaking us by casting every competition between human and artificial minds as a dramatic showdown. Such was the case of the coverage of Deep Blue vs. Kasparov, or the matches of DotA 2 played by OpenAI Five against professional human players.

As advancements in technology inevitably make their way into the mainstream and beyond the research-oriented domains of playing games, the sense of unease present in the population, and fueled by the press, grows. And it is not without reason that this dread exists – machines have, after all, already replaced humans in dirty, back-breaking and dangerous occupations. They act in lieu of factory workers and bomb disposal squads. They remove repetitive drudgery and danger, but also – most importantly jobs. The advent of AI means that, up until now thought as “too difficult for a machine” occupations, such as clerks or drivers, can now actually be performed by an automated worker. This, in turn, means that business owners can further optimize their processes – machines need no wages nor rest, and can operate indefinitely, provided maintenance and electricity. The lack of ability of humans to compete on those terms inspires obvious fears of the doomsday scenario coming true, as well as shocking headlines declaring that machines will replace humans.

The ensuing public debate about the shift towards AI-powered machine workers predictably circles around this area – if the machines are tasked with human jobs, what will become of humans? Economic experts are quick to calm down the imaginations of journalists, stating that this is but a repeat of the factory revolution of the early XX century, with the net amount of jobs ultimately increasing due to the formation of new industries – all that is needed is for workers to re-skill. The debate then typically goes through the motions of asking who would pay for the re-skilling and what about those who can’t manage, this in turn being countered by the need for public funding and government regulation.

The result of this atmosphere of competition between humans and machines, and the unceasing back-and-forth about jobs is turning the public’s concern away from the important question: that robots are going to take away jobs is a given, but the question of why would people still need to work is practically never raised. There is a logic to this, and it is this: by shifting the Overton window of the public debate onto what jobs humans should do to keep themselves economically afloat, one automatically avoids asking why, in the age of what should be common high quality of life, should they still do all of this work, or as much of it (if not more) than they used to. Why, in the age of booming productivity, do we still need all of these jobs? When are we going to finally reap the fruits of our labor in the form of leisure time and enjoyment?

The answers to this lie in the unmentioned premises. Just like AI is taken as a “necessary evil”, a sign of civilizational progress, the ever-present profit motive of capitalism is taken as a universal, almost metaphysical requirement. Thanks to this pre-framing, the extraction of surplus value from workers can continue unabated, in much the same way Smith and Marx described it when writing about capitalism, while the petty bourgeois commentators of liberal and conservative variety generate an illusion of debate over what amount of exploitation is fine before it breaches the boundaries of existing legal frameworks.

It is precisely this setup that is at the root of the problem. Inasmuch as everyone can agree on the ruthlessness of the machines and the unyielding, unfeeling logic according to which they operate (regardless of how well AI is taught to mimic feelings), the viciousness ascribed to the machines’ amoral stance is actually the viciousness of capital, seeking to maximize profit by any means necessary. The requirement to stay competitive in a global, fast-paced market gives rise to all the pathologies usually ascribed to the naivety of technocratic business leaders – perhaps sometimes to their individual greed. The fundamental necessity to appropriate the surplus value created by the labor of workers hasn’t changed, but only became more automated and optimized. Yet, the fundamental exploitative nature of the system is never brought into question by most public commentators, because to question the profit motive would be tantamount to questioning the existence of capitalism itself. This, in turn, would undermine the petty bourgeois commentators’ aspirations to one day ascend to the ranks of the elite, with material privileges that a position of celebrity hired speaker or author brings.

Let us therefore restate the original point: capitalism has no inherent interest in human well-being. It has undeniably increased humanity’s productive capacity, but the question isn’t of how much wealth is generated, but what happens to the wealth. Whether we talk about automated applicant tracking system which discriminate against ethnic minorities, a hyper-accurate deep-learning-powered face tracking system allowing intelligence agencies to track political dissidents in real time with no effort, or an app wishing to up-sell the user on a premium package after the algorithm has deemed them frustrated enough, the underlying logic is the same: maximize profit. Yes, there is a racist component in filtering out people with non-Anglo-Saxon names, there is a disturbing lack of ethics in supplying automated mass surveillance tools and intelligent weapons systems to various regimes, and there is a level of cultural acquiescence towards being nickel-and-dimed by a digital Skinner box, but beyond those ideals and idealistic interpretations of motives, there is an undeniable need to generate money.

The algorithms that keep humanity tied to their screens or help guide a missile onto their house are in and of themselves not the issue. It is the ever-present need to grow and out-compete that breeds all of the cultural, psychological and social pathologies that are ascribed to AI’s interference. It is the profit motive, not technology, that has led to the ever-increasing gap between wages and productivity, as pointed out by the Economic Policy Institute. It is the neo-liberal doctrine of turning every possible action or object into a commodity, inventing a set of measures to put it onto a hierarchy within a set of similar commodities, and then letting market forces establish its monetary value and distribution, that turns what is a labour-saving, revolutionary technology into a yet-another source of stress and anguish.

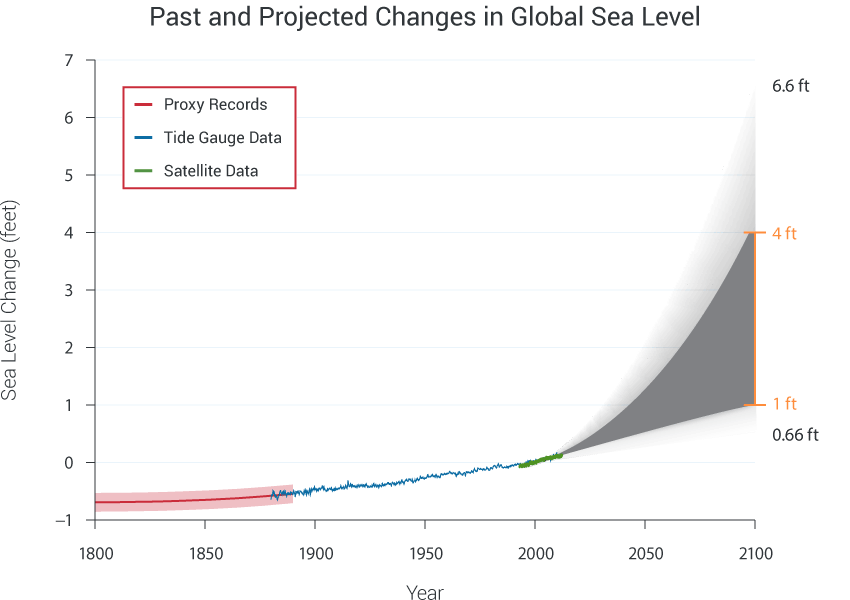

But the influence of capital doesn’t stop only on the areas affected by AI, of course. The need to expand and exploit the natural resources has already led to all the previous carbon emission goals being missed. With more alarms being sounded by the climate research community every year, and with increasing rates of natural disasters, the destruction of natural habitat and the ecosystem goes unimpeded. In fact, the disappearance of Arctic ice was recently hailed as a great new business venture opportunity. Between the lifting of limitations on drilling for oil in the Arctic in 2018 and the World Economic Forum hailing a group of new shipping routes opening because of the massive ice melt, the world’s capital wastes no time on turning an ecological disaster into profit.

The globalization of markets and the adoption of privatization policies worldwide has led to a decrease in availability of quality healthcare for the poorest, increase of public mental health crises, strained and defunded public schooling, and the dismantling of social safety nets under the guise of necessary budget savings. Since certain aspects of existence are inherently difficult if not impossible to measure objectively or assign monetary value to, like spiritual or cultural experiences, the neo-liberal recipe sees no use in them and they are thus swept aside, leading to closing down or downscaling of cultural institutions and reduction of interpersonal relations to those which are mediated by consumption of stereotyped, easy-to-produce mass media. In these and many other ways, capitalism is actively making the lives of all but the capitalists impoverished, more dangerous and threatened by ecological catastrophe. It elevates the most base of instincts – greed and desire to dominate others – while discarding every thing which doesn’t fit the confines of market valuation – regardless if it’s human or animal lives, or the fates of an entire ecosystem.

Ultimately the source of the biases and unfairness is not the ideals espoused by the people working within it, but the capitalist mode of production itself. The claimed failures of AI to provide for the people, to free them from the burdens of toil, to provide a neutral, instead of biased view of themselves, are actually the expressions of capital’s endless need to exploit, historical biases pre-existing in society expressed through reinforcement learning algorithms trained on biased data. It is not the fact that the progress in computer technology has been mostly the achievement of white, heterosexual males that is at the root of the issue – an all-African-American company would be under no different market pressure to exploit its all-African-American staff, comprised entirely of homosexuals, than the straight white counterpart. If it failed to do so, and to outperform its competition, it would vanish no less than the rest of now-defunct companies. The focus on AI as a rogue (or about-to-go-rogue) technology is a diversion from the discussion of the pressing matter of material relations enforced by capitalism, as it takes capitalist exploitation and all pathologies that exist because of it as a given, and re-routes the discussion onto the matter of dealing with it. If not stopped, capitalist profit motive will only accelerate in its destructiveness, as it cannot do anything else.

However, stopping it amounts to nothing less than stopping capitalism altogether. Various reformist notions which were meant to graft morality onto this system have been introduced in the past – the abolishment of child labour, the New Deal, various anti-monopolistic lawsuits. However, no amount of laws, regulations and restrictions can change the fundamental nature of the system. If told to not exploit workers as much in one jurisdiction, capitalists will move their productive capacity to another, so long as there is profit to be made – such was the case with deindustrialization of the United States, and the offloading of production to China. If told to take care of the environment by not utilizing certain dangerous chemicals, capital will use different ones, those about which the verdict of danger has not yet been made, if it can make a profit. Closing off all routes to exploitation would be tantamount to dismantling capitalism altogether, because its extraction of surplus value at the cost of other participants in the economy, whether it be exploiting workers or natural resources or the legal system, is – to use computer terminology – not a bug, but a feature.

As such, the system of parliamentary democracy offers little chance of enacting change. The notion that elected representatives, who received millions if not billions of dollars of campaign contributions, and are often business owners themselves, would rise against the system that feeds them is wholly unrealistic. Their future is no different than the future of managers in companies – they depend on the continued existence of capitalism for their own sake. Their track record of failing to prosecute and punish tax evaders and war criminals speaks for itself. Capital has the political system in the same stranglehold it has the economy. Here a typical call-to-action statement would be the urging of the workers themselves to organize and make demands to put an end to the exploitation. But with the diminishing wages and free time, stuck between a collapsing social welfare system and a collapsing healthcare system, endlessly distracted by an array of highly optimized, attention grabbing gadgets, such a proposition seems equally unrealistic.

AI will not destroy society, capitalism will.