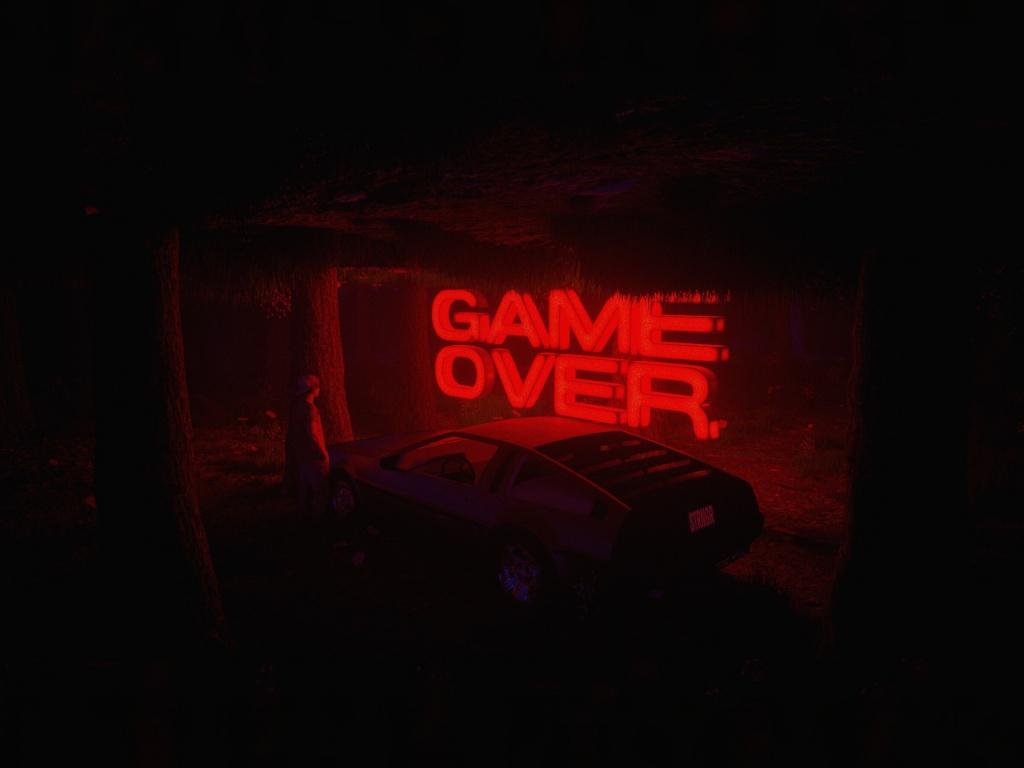

Game over. You have run out of life points (or credit score points). Envision, receiving a notification warning that states that you will be banned from society. Just as in a board game. One wrong move, you receive a card, and you end up landing on the Jail Space. It certainly seems science fiction as of now but there is more to be concerned about, particularly with the rapid development of modern technologies.

The revolution of technology has considerably facilitated and improved our daily lives. The next step in this process of evolution lies in the successful implementation of AI technologies in multiple areas of society. However, the conclusion of this can diverge. Several outcomes will be explored. In one version, it could help society flourish, and in the other, it could restrain it with the virtual chains of enslavement. What could possibly go wrong?

Can AI technologies enslave humans?

During the COVID pandemic period from 2019 until 2022, several measures of surveillance have been adopted as prevention for public health. Despite the initial good intention, the situation could be exploited as a method to normalize mass surveillance [1]. According to AlgorithmWatch, a non-profit that tracks ADM systems and their impacts on society, an abundance of automated decision-making (ADM) systems [1] have been implemented rapidly and with little transparency, inappropriate safeguards, and insufficient democratic debate since the onset of the coronavirus crisis. Digital contact tracing (DCT) applications and digital COVID certificates are two examples of ADM systems (DCC). AlgorithmWatch warns that these methods were adopted quickly and without regard for possible dangers and drawbacks. Such aggressive measures were considered only in a state of emergency and to aid the public. This should not become the new normal.

On the other side of the world in China, a similar system, Skynet, has been further developed in a more terrifying manner. It operates at least 200 million cameras [2] with an estimation, in 2020, of 600 million [3]. It also uses facial recognition [4], which is considered by others to be a violation of human rights. An open letter advocating for a worldwide ban on biometric recognition technologies that allow for mass surveillance and discrimination has been signed by 177 civil society organizations, activists, technicians, and other experts [5].

This is part of a broader approach for total mass surveillance. It has multiple components: the great firewall, digital monetary system control, communications control, and a credit score system.

To manage China’s Internet traffic, a nation-scale firewall known as the “Great Firewall of China” employs a variety of censorship and content filtering techniques. The firewall has been known to fail on occasion in the past [6].

By providing third-party mobile payment solutions, the country is becoming cashless [7]. The most famous China-based apps that are presently used are WeChat [8] and Alipay [9]. WeChat, with over 1 billion users [10], resembles traditional chat apps. Additionally, it has services such as cinema tickets, hotels, flash sales, housing, taxi booking, public transportation, parking, and so on. One notable feature is the app’s integration with the WeChat payment system. It also provides loans, mobile top-ups, and utility services. However, to use these services one must register with a phone number and a national ID card. To use Alipay’s My Car, a feature that helps you to pay for parking and insurance, one must add his driver’s license, license plate, and engine number. One can even book a doctor’s visit with the app.

Their government could oversee conversations in third-party messaging applications. In 2017 Puyang, Mr. Chen was sentenced to five days in prison for making a joke in a WeChat group [11]. The limit of its surveillance does not stop at its border, it could be that even outside the country they have the capability of doing so [12]. There is also evidence that they can use WeChat deleted messages [13].

Lastly, the social credit system [14]. Known as the Zhima Credit score [15] it provides a 3-digit score that goes as high as 1000 points. Having a higher score, for example above 700, entitles the user to favourable terms for loans or apartment rentals. Perhaps even better matches on a dating app with persons of a similar score. It is to be mentioned that in the popular press some articles [16] are contrary to the existence of the credit score system. But, the evidence gathered suggests that the system could be real and functioning.

With this final cog, this all comes together to form a sort of a total mass surveillance program where it could know quite much of every single citizen. Either be it private knowledge or public. It can access information about internet history, payment history, location, conversations, shopping habits, and public behaviour.

Another important factor is that the sheer number of operations that are required by that vast network of intricate mechanisms indicates the use of AI technologies to increase their speed and effectiveness.

Now let us look at a scenario where the credit score is not high. Supreme People’s Court blacklist (List of Dishonest People) it is the same list that is included into Zhima Credit [17]. The list has amassed a number of 7.49 million names. People who have been labelled untrustworthy in China are receiving their first taste of what a unified system could entail. In 2017, Liu Hu, a 42-year-old journalist, used a travel app to book a flight in May. The app informed him that the purchase would not go through because he was on the Supreme People’s Court blacklist when he submitted proof of identity. Liu was sued for defamation in 2015 by the subject of a piece he’d written, and a judge ordered him to pay $1,350. He paid the fine and even took a picture of the bank transfer slip, which he sent to the judge through text message, but no reply was received [18]. In other words, he became a second-class citizen. Banded from most means of transportation, he could only book the cheapest seats on the slowest trains. He was unable to purchase some consumer products or stay in high-end hotels, and he was denied substantial bank loans. To make it even worse, the blacklist was made public. After reporting on the shady transactions of a vice-mayor in Chongqing, Liu had already spent a year in prison on allegations of “fabricating and spreading falsehoods.”

One could argue that this type of surveillance reduces the crime index, according to Nee and Meenaghan (2006) [19] burglars have certain criteria when targeting a location such as vacant homes, and those with little or no nearby house surveillance. Armitage [20] suggests that other studies small studies seem to confirm this pattern. In some cases, CCTV may accidentally aid in the reduction of police misconduct [21]. The combination of CCTV and increased street lighting has been found to reduce property crime but has no influence on the frequency of violent crimes [22]. Yet, this can be only the case if they are used only for that purpose and not others. It can be debated that conclusive data about the possible modification of behaviour is yet to be available, thus more investigation is required. Other research suggests that the rising awareness of governments’ use of internet surveillance tools appears to have an impact on search behaviour [23].

Now that after having a little more knowledge about surveillance and what it can do, let us imagine, a hypothetical scenario, where a government has similar technologies but disregards the liberty of its inhabitants, if one person goes against their policy, with a push of a button, public services will no longer be accessible; and that person cannot travel, buy food or water, and cannot communicate with others. Let us hope that that scenario will remain just hypothetical.

So far it has been discussed about the influence of external factors but what if the influence comes at a subconscious level from our devices?

It was confirmed that in 2013, Cambridge Analytica used unknowingly the data of 87 million Facebook users to influence their behaviour and thus their vote in the 2016 presidential campaign. This analytical assistance was also provided in the Brexit referendum [24]. The revelation that Facebook provided unrestricted and illegal access to personally identifiable information (PII) has risen great concerns about privacy and safety [25]. The company has used algorithms that are based on ‘psychographic’ approaches that incorporate the so-called ‘Big Five’ personality traits: openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (OCEAN), which are well-known to many social psychologists. Over the last 35 years, social psychologists have increasingly used these characteristics to assess an individual’s personality. They gathered data by polling hundreds of thousands of people to evaluate their psychological profiles in exchange for free OCEAN scores. These tactics are so complex and dangerous that it was considered Weapons Grade Communication Tactics [26] because national interest and security were at risk.

This methodology was first introduced by two Ph.D. students DJ Stillwell and M Kosinski in 2007 for social research [27]. The approach was implemented in the MyPersonality app [28] and used the same technologies to harvest Facebook user data and predict personality traits. As a result, the social platform has suspended more than 400 apps that harvested personally identifiable information [29] and received a penalty of $5 billion [30] in the USA and £500,000 [31] in the UK.

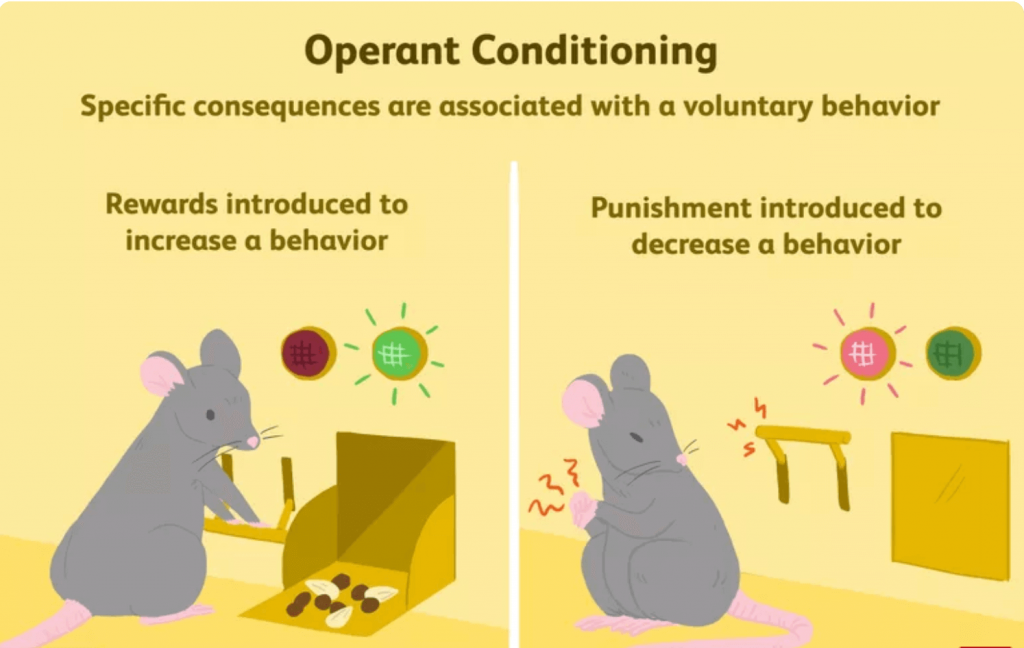

This is not the only mischievous approach that is presently used. It is known that several apps, social media, and games can cause addiction [32]. Some make use of the Compulsion Loop [33], a repetitive chain of behaviours that the user will repeat to keep them engaged in the activity. This loop is usually set up to give the user a neurochemical reward, such as the release of dopamine. They are explicitly utilised as an extrinsic motive for players in video games, but they can also result from other behaviours that create such loops, whether intentionally or unintentionally, such as gambling addiction and Internet addiction illness. The loop can create obsession behaviour [34].

B.F. Skinner originally presented this concept in 1930 [35]. He was studying operant conditioning, also known as instrumental conditioning, which is a learning approach that uses incentives and punishments to influence behaviour or volition with active choice. An association is formed between a behaviour and a consequence (whether negative or positive) for that behaviour through operant conditioning. The experiment was conducted in a closed contraption with a bar or key that an animal subject (pigeon or rat) can operate to gain reinforcement. It is now known as Skinner’s Box method [36].

Davidow [37] suggests that many internet companies use mechanisms that cause addiction, since it increases earnings. Husin et al. [38] conducted a test that revealed that a variance of 63.4% (R2) of TikTok [39] addiction could be explained by social, family, and lifestyle factors. Another study [40], identified that people who use social media sites at least 58 times per week are three times more likely to feel lonely and depressed.

With an estimated 330 million people that potentially suffer from Internet Addiction in 2022 [41], proper measures and studies are suggested to be taken to alleviate this matter.

But to understand the root of this issue one must question what is addiction and its causes?

J. Hari [42] proposes that disconnection from human relationships drives addiction and to aid, a reconnection with the world is suggested so that compulsions are left behind. It is a different approach, instead of denying or punishing the usage of a smartphone. This way provides an alternative to creating more meaningful interactions.

G. Mate [43] also concludes that based on the literature review that stress mechanisms in children can be influenced by abandonment, neglect, or multiple forms of abuse. This could result in a more susceptible to stress later in life. Substance misuse or dependency are linked to the effort of finding release from a stress reaction.

There are options to consider when it comes to punishing citizens for certain behaviours caused by addiction. As a solution for video game addiction, some studies suggest a more punitive approach, another instead recommends a less punitive approach [44]. In Portugal, a radical approach was taken. Rejecting criminalization of minor offences for substance possession and scaling up health services and the reinsertion into society [45]. This was one of the factors that helped to reduce addiction to substances over time.

Based on research, several software programs have started to implement a mechanism that could reinforce certain behaviours; that may, in the end, cause addiction; and the reason seems to be economical; to just increase revenue. Certainly, other factors are involved but the voluntary design and implementation of Skinner’s box method should be held liable. Since, social media, games, and apps are becoming part of our daily lives, a multitude of medical experts should be included in the design process to avoid these types of products.

Can AI technologies free humans?

Finally, to the positive side of AI.

Automatization has the potential to reduce human labour. A factory in China has replaced 90% of human labour [46]. It could also do jobs that involve high risk for humans Furthermore, AI might speed up the research for diseases thus improving the quality of life. Microsoft developed an AI to assist cancer doctors to find suitable treatment [47].

If in the future automatization replaces a substantial percentage of physical labour, a universal income is advised.

By reducing time spent on redundant jobs humans could do something more meaningful. A debate could be held as to what is meaningful work or not but that would prove unfruitful, hence the conclusion of the research [48] will be presented. However, it can be noted that people will have different experiences with the same job bases on their character, capabilities experience, or preferences.

To begin with, conducting meaningful work is associated with higher job satisfaction and employee well-being [48].

Second, many of us work for a significant portion of our week. So, if robots will have a negative impact on meaningful employment in general, it will have a significant impact on how humans live [48].

Lastly, various philosophers have argued that society owes it to its citizens to ensure that they have access to meaningful labour [48].

Smids et all. [48] identified in literature dimensions of, pathways to, and sources of meaningful work. On that basis, the authors articulated that work is meaningful if it entails pursuing a purpose, social relationships, exercising skills and self-development, self-esteem and acknowledgment, and autonomy.

People’s attitudes suggest that there is a preference for people to have jobs that involve art, evaluation judgment, and diplomacy [49]. Instead of robots, they are preferred to have a task that demands memorization, high perceptual ability, and customer service [49]. Surprisingly, people will be more favourable towards robots doing work alongside humans rather than in the place of humans [49].

Possible solutions

Solutions for these complicated issues are certainly not easy to discover, it is an ongoing process. Nevertheless, several have been identified.

An independent body that governs AI without being influenced by external factors is desired.

The United Nations is an International organization that was founded in 1945. Presently it has 193 Member states. Its mission is to uphold international law while maintaining peace and security, protecting human rights, delivering humanitarian aid, supporting sustainable development and climate action, and maintaining peace and security [50]. Its importance is significant. Whilst the organization is committed to being impartial and not influenced by outer constituents, it is, unfortunately, dependent on income streams. The distribution of the funding system is divided into 2 categories: assessed and voluntary contributions. The first one is a constantly fixed payment that is required to be made by the UN Member States under the UN Charter. The disparity between the contributions is disconcerting. From 2010 to 2019 the percentage for assessed contribution [51] has decreased from slightly over 30% to 24%. In contrast, the voluntary one has increased from 50% to 57.8%.

Funding origin can influence results [52]. This could be true even for large organizations. Conflicts of interest should be avoided for unbiased academic research. It is advised that science should be publicly funded thus, it would allow more impartiality.

Centralisation is what causes the scenario where society is constrained. Decentralized technologies or blockchain, is a sequential distributed encrypted database used in bitcoin-based currency. The technology can be used to avoid digital currency control and other services. Instead of having one entity controlling and owning the service, it can be distributed amongst people and owned by the users.

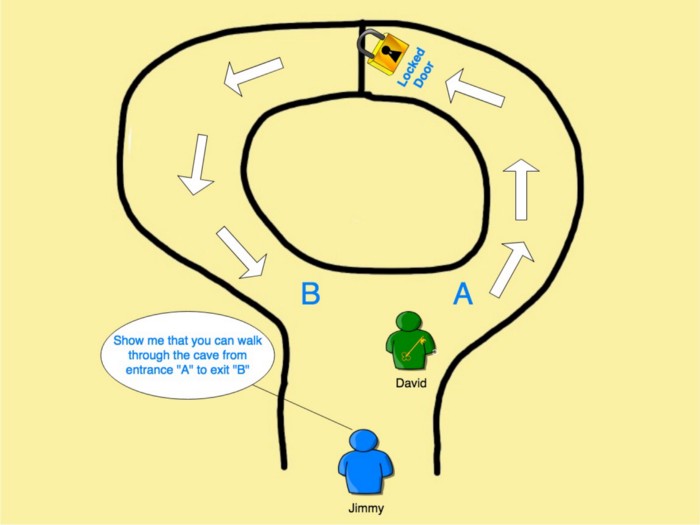

As to ensure that privacy is respected, the Zero knowledge proofs [53] concept [54] is recommended. It uses mathematics to prove the truthfulness of an interaction or a statement between two people, a prover, and a verifier. It allows proving that without giving details. The concept is further clarified in the image. Z cash [55] is an open-source project that uses cryptocurrency techniques and Zero-knowledge proofs.

As for having a safer AI, the WHA recommends six principles to ensure AI in all countries serves the public interest [56]. They are the following:

- Human autonomy must be protected.

- Promoting individual health and safety, as well as the public good

- Ensure transparency, explainability, and comprehension.

- Promoting accountability and responsibility

- Ensure fairness and inclusivity

- Promoting AI that is both responsive and long-term

Regrettably, corporations do not always have the best interest of their users. Its main objective, usually, is to increase profits and to please its investors. A fine is not enough to stop multibillion corporations, as they will always have more than enough to spare. More drastic measures that could limit their reach need to be considered. Holding platforms accountable [57] could change the way they operate.

Considering that many could have their lives impacted by these technologies, ultimately the decision should be a democratic one; with no external influence based on academic studies with empirical data. By doing so the public will be well informed when deciding such matters. Let us hope and act to achieve the best outcome the future has to offer by treading carefully and choosing wisely.